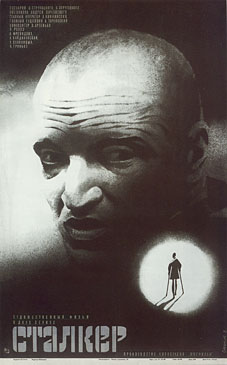

Danger! High-radiation arthouse! | Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker.

Tag: Andrei Tarkovsky

The Stalker meme

The Stalker’s dream from Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979).

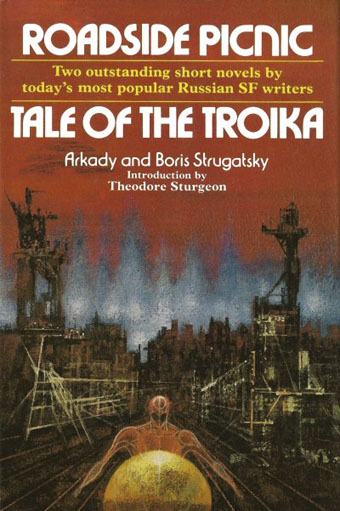

The innocuously-titled Roadside Picnic is a Russian science fiction novel by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, first published in 1972:

Aliens have visited the Earth, and departed, leaving behind a number of artefacts of their incomprehensibly advanced technology. The places where such artefacts were left behind are areas of great danger, known as ‘Zones.’ The Zones are laid out in a pattern which suggests that they resulted from the impact of an influence from space which struck repeatedly from the same direction, striking different places as the Earth rotated on its axis.

A frontier culture arises along the margins of these Zones, peopled by ‘stalkers’ who risk their lives in illegal expeditions to recover these artefacts, which do not obey known physical laws. The most sought one, the ‘golden sphere’, is rumoured to have the power to fulfill the deepest human wishes.

The name of the novel derives from a metaphor proposed by the character Dr. Valentin Pilman, who compares the visit to a roadside picnic. After the picnickers depart, nervous animals venture forth from the adjacent forest and discover the picnic garbage: spilled motor oil, faded unknown flowers, a box of matches, a clockwork teddy bear, balloons, candy wrappers, etc. He concludes that humankind finds itself in a situation similar to that of the curious forest animals.

UK paperback, 1977; cover art by Richard Powers.

Surprisingly for a novel that’s still very much in copyright, a number of online versions are available, including this PDF. The Strugatsky’s idea seems to be a particularly attractive one for reasons that aren’t immediately clear. Is it because it works an sf twist on old fairy tales or myths such as Theseus and the Minotaur? Or is the central conceit of drawing a boundary around a dangerous area then sending in your characters the one that strikes a chord?

Whatever the answer—and with the Zone we can’t necessarily expect answers—Roadside Picnic was brilliantly filmed by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1979 as Stalker. Tarkovsky described the film’s production in his diaries as cursed; there were arguments with the original cinematographer and problems processing the film that ruined many of the original takes. The film was more cursed than he realised. Unbeknownst to the crew, the area around an old power station in Tallinn, Estonia, which provided many of the Zone’s ruins was highly polluted. This only became apparent several years later when cast and crew began dying prematurely. Tarkovsky himself succumbed to cancer in 1986. It’s impossible to avoid thinking of this when watching the film, especially when you see the actors wading into filthy water.

Whatever the answer—and with the Zone we can’t necessarily expect answers—Roadside Picnic was brilliantly filmed by Andrei Tarkovsky in 1979 as Stalker. Tarkovsky described the film’s production in his diaries as cursed; there were arguments with the original cinematographer and problems processing the film that ruined many of the original takes. The film was more cursed than he realised. Unbeknownst to the crew, the area around an old power station in Tallinn, Estonia, which provided many of the Zone’s ruins was highly polluted. This only became apparent several years later when cast and crew began dying prematurely. Tarkovsky himself succumbed to cancer in 1986. It’s impossible to avoid thinking of this when watching the film, especially when you see the actors wading into filthy water.

Stalker is available on DVD in a less-than-satisfactory transfer (annoyingly spread across two discs) but at least it doesn’t suffer the sound fault that plagues the DVD of Nostalgia. Nostalghia.com is the best Tarkovsky site, with several Stalker-related features.

The most notorious example of Soviet-era pollution is, of course, the Chernobyl disaster which occurred a few years after Stalker. In one of those typical examples of life imitating art, the 1,400 square mile quarantined area around the power station is referred to as the Zone of Alienation, the Chernobyl Zone, the 30 Kilometre Zone, the Zone of Exclusion or the Fourth Zone. Scientists who study the forbidden region (and guides who take people there illegally) have referred to themselves as “stalkers”. This site features a huge amount of photographs of the abandoned buildings inside the radioactive area. Bldgblog also has a photo feature.

The Stalker meme has infected the music world. In addition to soundtrack albums by composer Edward Artemyev, Robert Rich and Lustmord produced Stalker in 1995, a marvellously atmospheric album of dark ambience inspired by Tarkovsky’s film.

Latest work to explore the theme is Nova Swing, a science fiction novel by M John Harrison. This book is set in the same future as his excellent Light, “less a sequel…than an independent novel set in the same general universe.”

We are in a city, perhaps on New Venusport or Motel Splendido: next to the city is the event site, the zone, from out of which pour new, inexplicable artefacts, organisms and escapes of living algorithm—the wrong physics loose in the universe. They can cause plague and change. An entire department of the local police, Site Crime, exists to stop them being imported into the city by adventurers, entradistas, and the men known as ‘travel agents’, profiteers who can manage—or think they can manage—the bad physics, skewed geographies and psychic onslaughts of the event site. But now a new class of semi-biological artefact is finding its way out of the site, and this may be more than anyone can handle.

You can read an extract from Nova Swing here.

I don’t think we’ve heard the last of the Stalkers. The Strugatsky’s story seems like the Zone itself, leaking an influence into the surrounding culture that then mutates into strange new forms. It seems you can’t keep a good meme down or, for that matter, contained.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Nova Swing

• Solaris

The Disasters of War

7 ¶ And when he had opened the fourth seal, I heard the voice of the fourth beast say, Come and see.

8 And I looked, and behold a pale horse: and his name that sat on him was Death, and Hell followed with him. And power was given unto them over the fourth part of the earth, to kill with sword, and with hunger, and with death, and with the beasts of the earth.

Revelations 6

There are horror films, there are films about the horror of war, and then there is Elem Klimov’s Come and See (Idi i Smotri). Klimov made the film in 1985 from a screenplay by Ales Adamovich based on that writer’s experiences as a young Russian partisan fighting the Nazis during the Second World War. This biographical quality may be what gives the film its incredible immediacy and authority (Klimov also suffered as a child during the war) even though its power is obviously a product of Klimov’s skills as a director.

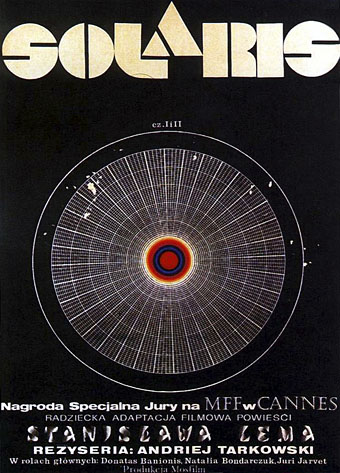

Solaris

This wonderful poster was designed by Andrzej Bertrandt for the Polish release of Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1972 film of the novel by Stanislaw Lem. Lem didn’t like the film, referring to it as “Crime and Punishment in space”, which is a fair description seeing as it’s filled with the same lengthy moral discussions as Tarkovsky’s other films.

There are more posters and pictures at the great Tarkovsky site Nostalghia.com. Also lengthy quotes and interviews about all his films:

I don’t like science fiction, or rather the genre SF is based on. All those games with technology, various futurological tricks and inventions which are always somehow artificial. But I’m interested in problems I can extract from fantasy. Man and his problems, his world, his anxieties. Ordinary life is also full of the fantastic. Life itself is a fantastic phenomenon. Fyodor Dostoievsky knew it well. That’s why I want to focus on life itself—everyday, ordinary. Because within it anything can happen. My Solaris is not after all true science fiction. Neither is its literary predecessor. What counts here is man, his personality, his very persistent bonds with planet Earth, responsibility for the times he lives in. I don’t like your typical science fiction, I don’t understand it, I don’t believe in it. The fact is when I was working on Solaris I was concerned with the same subject as in (Andrei) Rublev. Human being. These two films are only separated by the time the action is taking place.