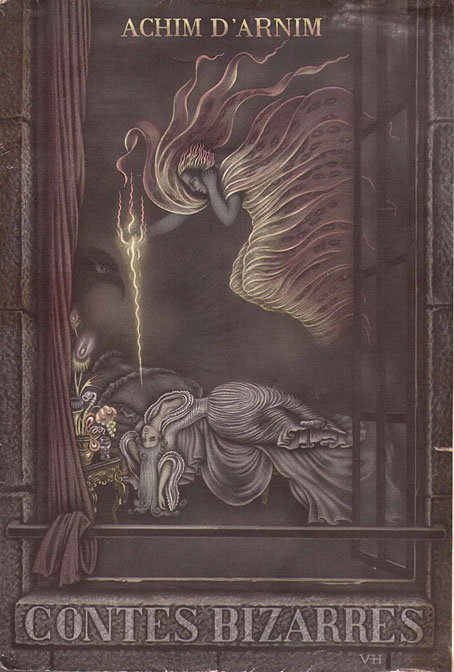

Art by Diego Rivera for the Mexican supplement in Minotaure no. 13.

I was tempted to title this one Minotaure! since I’ve been searching for copies of the magazine in question for many years. I’m certain I went looking in all the usual sources last year in the run-up to the Surrealist centenary, without success. Anyway, here they all are at last, a complete run of one of the major Surrealist periodicals.

Minotaure was notable for a number of reasons, first among them the publisher, Albert Skira, whose resources enabled the production of a very desirable item, with good design, colour prints in each issue, and plenty of photos and other artwork throughout. The Surrealist publications of the 1920s had been historically important but all of them were monochrome documents with few pictures and few pages. Minotaure had the production values of a quality magazine and an impressive roster of artists and writers to fill each issue. Skira and editor E. Tériade originally intended their periodical to cover a wide range of art, past and present, but with most of the early contributors being members of André Breton’s Surrealist circle the magazine quickly became a showcase for Surrealist art and theorising. The first issue featured a cover by Pablo Picasso, with more Picasso artwork inside. Subsequent issues had covers by leading Surrealist artists–Dalí, Ernst, Magritte, Masson–which captured the movement at a time before Breton’s persistent expulsions hollowed out the original group. Breton writes in nearly all the issues but was forbidden from using Minotaure as a political platform (the previous Surrealist journal had been the very political Le Surréalisme au service de la révolution), a restriction he kept to. His manner was often dictatorial but he always had an eye for the main chance, or the bonne chance in this case.

The written contents of Minotaure are mostly in French but the pictorial matter is worth seeing even if much of it is very familiar today. Among the written highlights are two essays by Salvador Dalí, the first on the “edible” nature of Art Nouveau architecture, with an emphasis on the work of Gaudí; the second about Pre-Raphaelite painting. It’s understandable that Dalí would be attracted by the meticulous realism of early Millais and William Holman Hunt but I didn’t know his essay included an analysis of Hunt’s The Hireling Shepherd, a painting I look at every time I’m in the Manchester Art Gallery. Elsewhere there are articles about automatism, mediumship, the decalcomania technique in painting, the esoteric symbolism of the alchemists, naive or untutored art, and plenty of single-page items and visual novelties. Photography by Man Ray and Brassaï is a recurrent feature. Skira’s magazine established a template which the two American Surrealist periodicals of the 1940s, View and VVV, did their best to follow. Now that Minotaure is freely available I’ll be waiting impatiently for complete runs of its followers to turn up somewhere.

(Note: some of the copies linked below have had their colour prints removed.)

Minotaure no. 1 (1933)

Cover art by Pablo Picasso.

Minotaure no. 2 (1933)

Cover art by Gaston-Louis Roux.