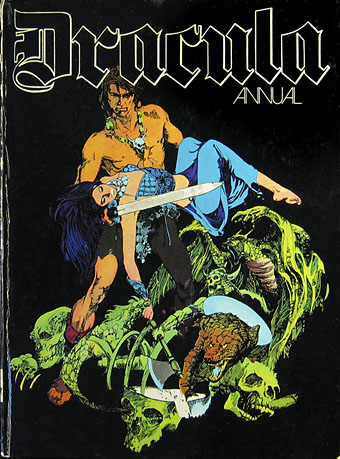

A comment by Modzilla in last month’s post about psychedelic comic book Saga de Xam is responsible for this recent book purchase. Dracula was a full-colour large-format comic book from notorious pulp imprint New English Library (later to be distributors for my colleagues at Savoy Books) that repackaged Spanish horror strips for a British audience. The comic ran for 12 issues in the early 1970s; the pages shown here are from the hardback annual that gathered all the issues into a single volume. I remember this being around in secondhand shops for years but I never paid it any attention at all so the artwork has been a revelation.

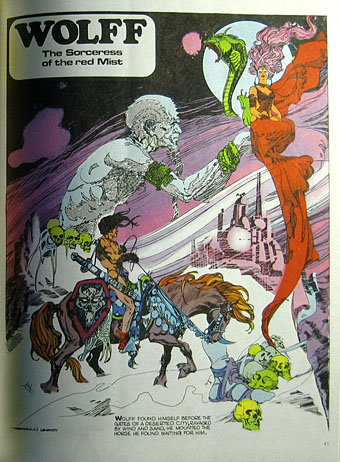

NEL’s Dracula isn’t much of a horror comic, despite its title; Dracula himself only appears in one story, and that’s a jokey throwaway piece. The two main episodic strips are Wolff, a Conan clone searching for his lost wife in a world ravaged by witches, werewolves and other supernatural threats; and Agar-Agar, a deliriously psychedelic picaresque concerning a hyper-sexual “sprite” (or a hippyish young woman with blue hair and magic powers) from the planet Xanadu. Everything in the book is redolent of the early 1970s when strains of psychedelia were still percolating through pop culture. Watered-down psychedelia used to bore me because I wanted the authentic stuff but forty years on this kind of work is much more attractive.

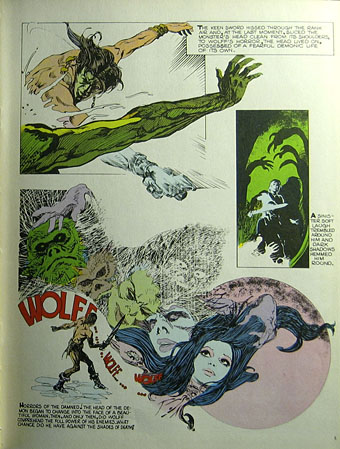

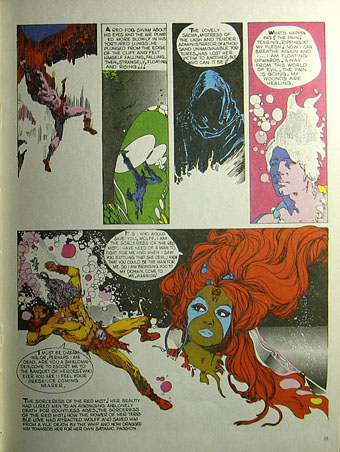

Wolff is the work of Esteban Maroto whose splash pages and inventive layouts give Barry Windsor-Smith’s Conan the Barbarian (which was running at this time) some serious competition. Wolff is very much in the Conan mould—he even shouts “Crom!” at crucial moments—a pawn of supernatural forces he often fails to comprehend. The artwork in Smith’s Conan was often praised for its details and decor but the Art Nouveau influence in Maroto’s work is much more overt. Maroto’s flame-haired witches are like Alphonse Mucha sirens—one panel even borrows from Mucha’s Salammbô—and he’s no slouch with the Frazetta-like demons either. The scripting is perfunctory but I don’t mind that when it turns up pages like these. There’s also a brief nod to Lovecraft when “R’Lyeh” is mentioned.