Takato Yamamoto was born in Akita prefecture (Japan) in 1960. After graduating from the painting department of the Tokyo Zokei University, he experimented with the Ukiyo-e Pop style. He further refined and developed that style to create his “Heisei Esthiticism” style. His first exhibition was held in Tokyo, in 1998.

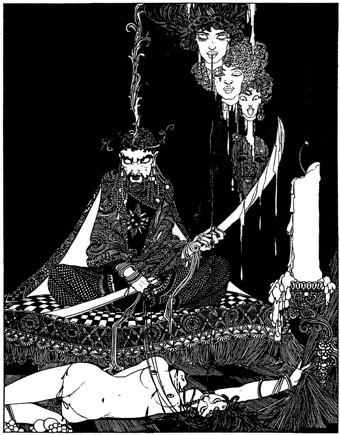

There’s much that’s superficially familiar in Takato Yamamoto’s art—“Boy’s Love” tableaux with fey young men in various states of undress mooning over each other, then the perennial Japanese obsession with naked women bound by ropes. But closer examination reveals a degree of finesse and imagination that elevates his work away from the porn ghetto into the rarified realm of Decadence (as if those favourite Symbolist themes of Saint Sebastian [above] and Salomé [below] weren’t enough of a clue). For a start the drawing style is a great amalgam of influences from Beardsley through to Harry Clarke by way of the finest Edwardian pornographer, Franz von Bayros. Then there’s the curious details of severed heads, claws, sundry bones and eyeballs which decorate the otherwise florid arrangements supporting the figures. So far there don’t appear to have been any books of Takato Yamamoto’s work produced in the west and it’s possible that the sexual content and grotesquery limits that possibility. But you can some galleries here, here and here. His official site is mostly Japanese and has to be navigated from an interior page since there seems to be a file missing from the index.