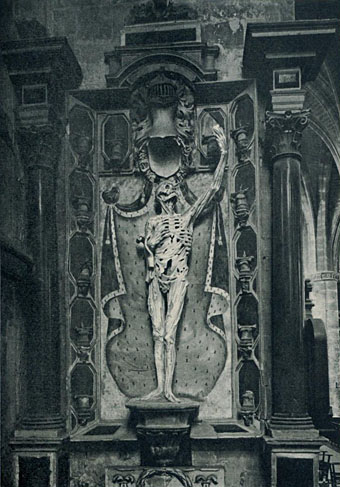

Another recent piece of Angeriana, and another short video sketch, Brush of Baphomet (2009) is a kind of addendum to Anger’s The Man We Want to Hang (2002), being a further look at Aleister Crowley’s paintings. The title refers to one of Crowley’s many occult names. As a painter Crowley’s technical ability was almost nil but that never dissuaded him from trying, and I’m sure I’m not alone in finding his work to have a naive malevolence. Anger has had a lifelong interest in Crowley’s paintings, famously journeying in 1955 to the abandoned villa in Cefalù, Sicily, where he cleaned whitewash from the walls to reveal the remains of the murals Crowley had painted there.

The music in Brush of Baphomet is a surprising choice, an extract from the second part of Morton Subotnick’s Silver Apples of the Moon (1967). Anger’s musical selections have never been random ones so you have to wonder why this particular score. Was it because the electronics are reminiscent of the Moog drones Mick Jagger supplied for Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969)? Subotnick’s title is borrowed from The Song of Wandering Aengus by WB Yeats, a poet for whom Crowley (also a poet) had little affection. In Crowley’s occult novel Moonchild, Yeats appears as “Gates”, a mediocre painter (yes, well…), who ends up being killed in an act of magical revenge. Crowley must have been mortified a few years later when Yeats was awarded a Nobel Prize.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Anger Sees Red

• Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon

• Lucifer Rising posters

• Externsteine panoramas

• Missoni by Kenneth Anger

• Anger in London

• Arabesque for Kenneth Anger by Marie Menken

• Edmund Teske

• Kenneth Anger on DVD again

• Mouse Heaven by Kenneth Anger

• The Man We Want to Hang by Kenneth Anger

• Relighting the Magick Lantern

• Kenneth Anger on DVD…finally