For many directors a film like Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) would have been a career peak, but Friedrich Murnau went on to make The Last Laugh (1924), Faust (1926) and Sunrise (1927). All those films improve cinematically on Nosferatu but the vampire film continues to cast the longest shadow: quoted, remade, and with even its production fictionalised in Shadow of the Vampire (2000). The lasting success of Nosferatu wasn’t all Murnau’s doing, however.

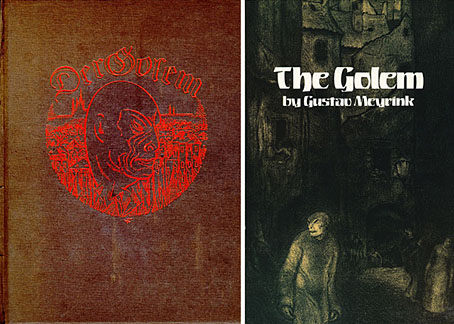

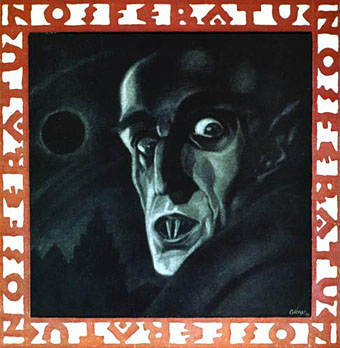

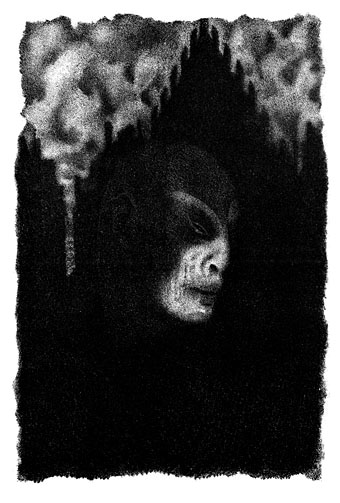

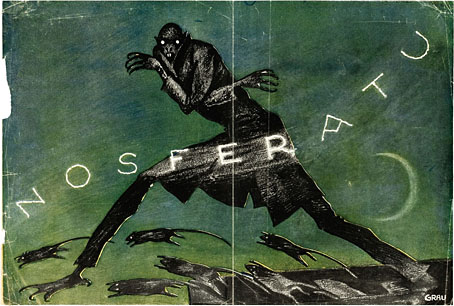

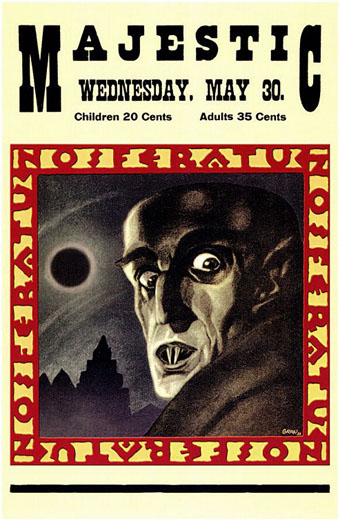

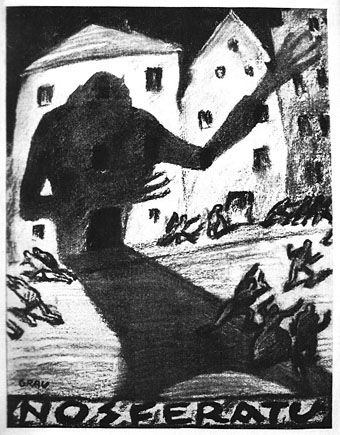

It’s arguable that without the preliminary work of production designer Albin Grau (1884–1971) the film might have been little more than a curious precursor of the Universal Dracula (1931). Grau was responsible for the set design and the extraordinary appearance of Max Schreck’s Count Orlok; Grau also created the film’s memorable poster and advertising imagery in which the vampire’s appearance hints at something even more terrible than the figure that stalks before the camera.

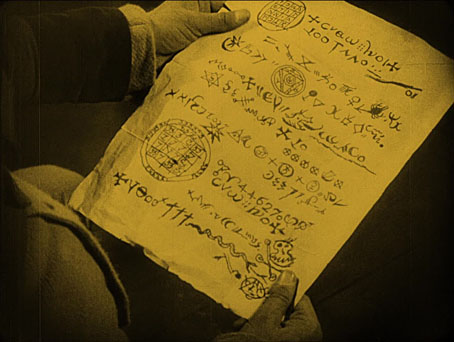

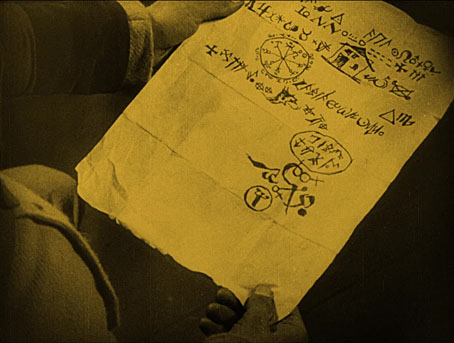

A great deal of German silent cinema is labelled “Expressionist” even if the films themselves show little in the way of overt Expressionism. Nosferatu isn’t very Expressionist at all but Albin Grau’s sketches and posters certainly tend in that direction, so much so that they make me wonder how different the film might have been if it had been as stylised as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919). In addition to his artistic pursuits, Grau was an occultist which explains the attention to detail in the bizarre contract drawn up between Knock and Count Orlok, a document that looks more like a page from a grimoire than anything used by an estate agent. There’s a quote from Grau in his occult capacity in John Symonds’ Aleister Crowley biography, The Great Beast, complaining in 1925 about Crowley’s ascension to the heights of the Ordo Templi Orientis.

Nosferatu: The Knock-Orlok contract.

Nosferatu comes out of the occult preoccupations, having been Grau’s project from the beginning when he formed a film company, Prana-Film, with Enrico Dieckmann. The pair announced plans for three films: Dreams of Hell, The Devil of the Swamp, and a drama about a vampire. Only Nosferatu materialised then sank the company almost as soon as it was finished: Prana-Film had spent more on publicity than on the film itself, and went deep into debt. The success of the film might have helped their finances but the death blow was struck by Florence Stoker and the British Society of Authors who won a court case against the company for filming Dracula without permission. The efforts of the Stoker estate to destroy Nosferatu are recounted in detail in David J. Skal’s fascinating Hollywood Gothic (1990). Many of Murnau’s minor films were lost through various misfortunes, and it’s a fluke that a handful of prints of Nosferatu survived. Happily for us, it’s not only vampires that manage to remain undead.