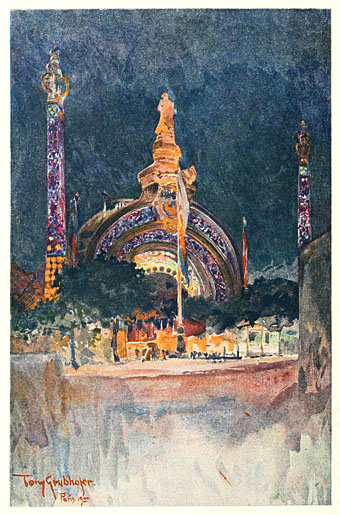

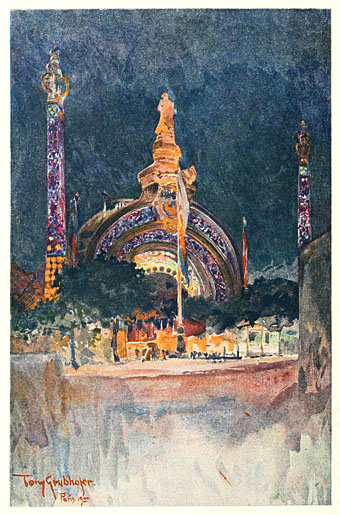

The Exposition gateway.

In a blizzard of work this month I finished another project with a Victorian theme (not more Steampunk!) which I won’t reveal just yet as I dislike spoiling the surprise for publishers. Part of the preparation involved yet more trawling through scanned volumes at the Internet Archive, looking this time at British art magazines from the 1890s. As with the German magazines of the period, some of these are more interesting than others: The Magazine of Art, for example, has its moments but for the most part it’s a champion of the stodgily dull, conservative fare which no one would ever want to revive today. Their columnists also hated the Decadents; I found a wonderful rant against Aubrey Beardsley’s art from 1897 which suggested that the artist and others like him ought to stop poisoning the soul of the nation and emigrate to France. Poor Aubrey only had a year to live, and, as things turned out, ending up dying in that iniquitous nation. I think it’s fair to say he’s had the last laugh.

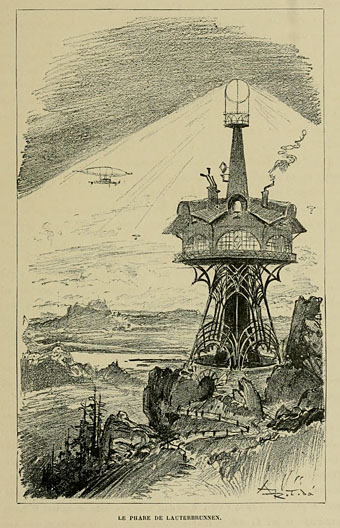

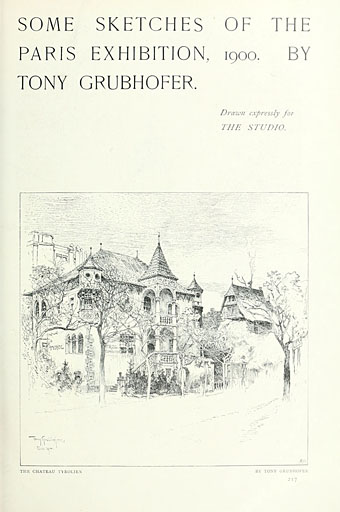

The Chateau Tyrolien.

The Studio magazine, on the other hand, was very sympathetic to the Decadents and Symbolists in general, and to Beardsley in particular, who had his work featured in the first number of the magazine in 1893. The drawings in this post are a surprise find in one of the numbers for 1900, and concern that locus of everything The Magazine of Art loathed: Paris! We’re back again at the Exposition Universelle, a subject which has been explored here on so many occasions I’m surprised I keep finding anything new that’s worthy of mention.

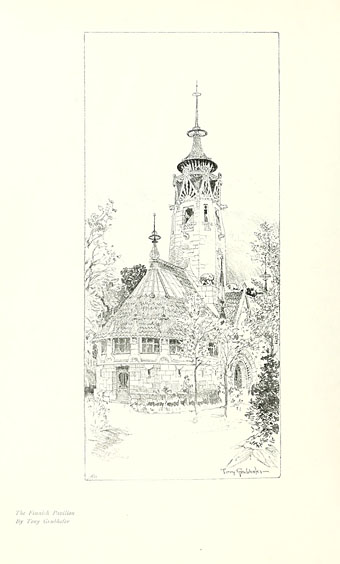

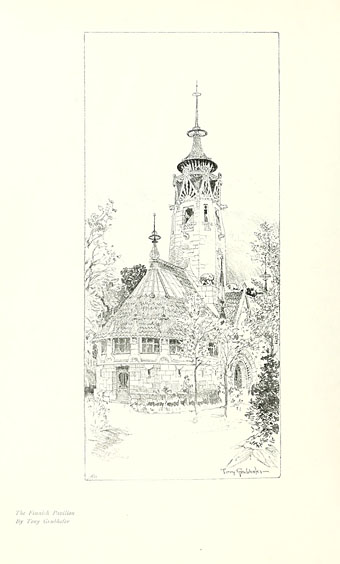

Tony Grubhofer (1854–1935) was apparently an Austrian artist who in these drawings manages to crop his views so selectively that many of them don’t look like they’re part of an exposition in one of the world’s capital cities. Of interest for me are his watercolour of René Binet’s monumental gate, which gives an idea of how the structure would have looked at night illuminated by the novelty of electric light, and his view of Eliel Saarinen’s Finnish pavilion which he renders as though it was a provincial church. This was Saarinen’s first major commission (he was 27 at the time), and Philippe Jullian in his book about the exposition declares this design to have been the most interesting and successful of all the national pavilions that year. It’s certainly better than Edwin Lutyens’ pastiche of an Elizabethan manor for the British pavilion. Eliel Saarinen had a very successful career, as did his more well-known son, Eero Saarinen, one of the major architects of the 20th century.

Volumes 20 to 22 of The Studio can be downloaded here.

The Finnish Pavilion.

Continue reading “Tony Grubhofer’s Exposition Universelle sketches”