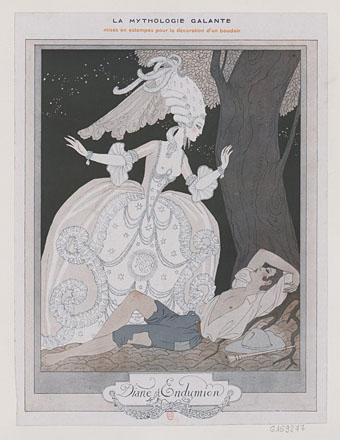

The haute couture of the 1920s has been the subject of my latest work-related research so I’ve been going through back issues of Gazette du Bon Ton, an expensive French fashion magazine which used pochoir prints of drawings by a variety of illustrators to depict the latest dress designs from Paris. One of the regular Bon Ton contributors was George Barbier (1882–1932), an artist whose work has appeared in several posts here, and who I look for now and then when browsing library archives. Searching for new Barbier may be at an end, however, since the more recent uploads at Gallica include almost all of the books that he illustrated. It’s no surprise that these have turned up eventually—it was only a matter of time—but among the cache there’s a unique item that I’d never have expected to see.

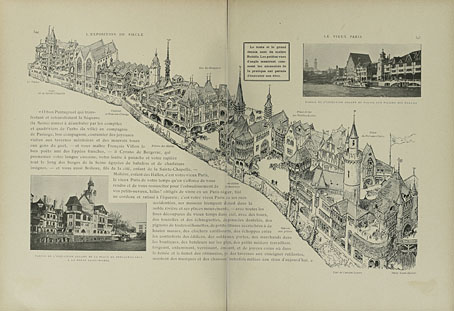

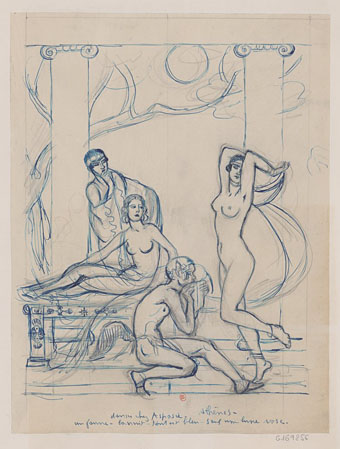

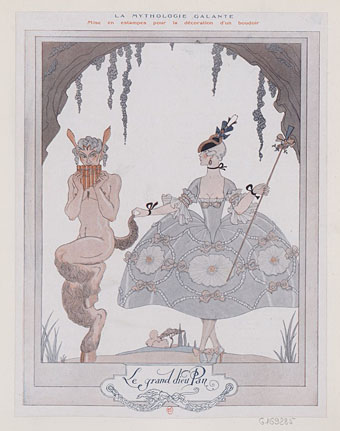

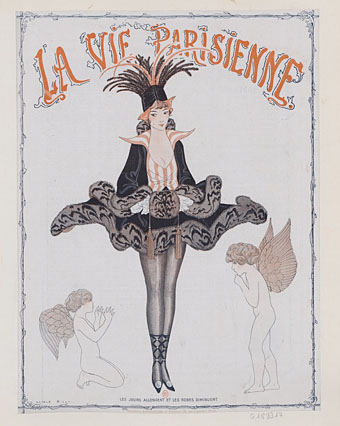

Dessinateurs et humoristes is a scrapbook of odds and ends covering Barbier’s career from 1912 to 1924, mostly humorous illustrations for magazines such as La Vie Parisienne, but the collection also includes handwritten material together with many sketches and drafts for unfinished drawings. This is part of Gallica’s “Collection Jaquet”, 113 scrapbooks collecting magazine work by French illustrators. I’ve not had the time to go through the rest of the collection but there are many familiar names in the list, each with books of their own: Albert Robida, Théophile Steinlen, two volumes dedicated to the prolific Gustave Doré, etc. Gallica’s information about these items is minimal so for now the identity of “Jaquet” remains a mystery. As for the Barbier scrapbook, if you like the artist’s drawings this is a delight to look through, a cornucopia of camp frivolity replete with all the usual crinolined ladies, powdered wigs, mischievous Cupids, tiny dogs, and almost as many nude males as there are females. There’s also a picture bearing the title “The Great God Pan” although as a representation of the deity it’s closer to Aubrey Beardsley than anything from Arthur Machen.

Continue reading “Dessinateurs et humoristes: George Barbier”