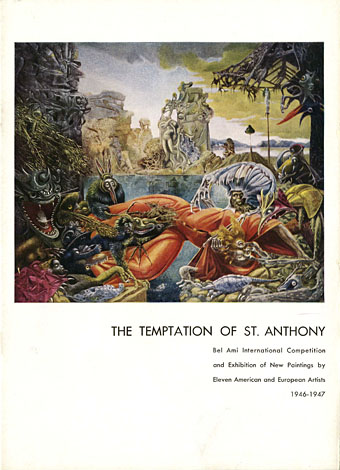

Exhibition catalogue.

In one of the many recent features about Leonora Carrington I noticed a mention of her Temptation of St Anthony painting from 1945 (see below). This was one of eleven works on the theme submitted by different artists for a competition staged to promote Albert Lewin’s The Private Affairs of Bel Ami (1947), a film adaptation of the Guy de Maupassant novel. Carrington is often mentioned when this competition is discussed, along with the other big names, Max Ernst (the winner) and Salvador Dalí. But you seldom see mention of any of the other competitors, hence this post, an attempt to find all of the competition entries.

Leonora Carrington. St. Anthony is often shown with a pig companion but only Carrington depicted the animal for this competition. When asked why the saint had three heads, she replied “Why not?”

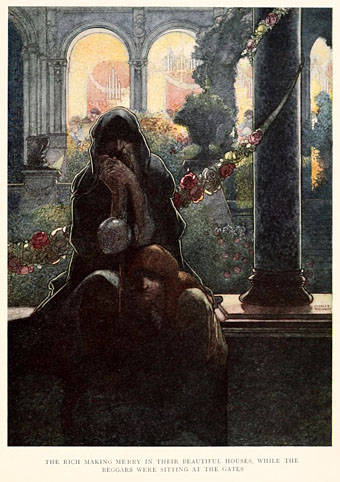

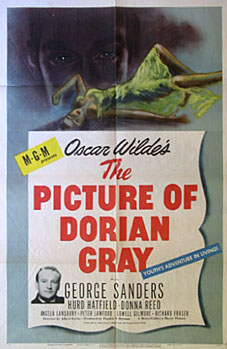

Albert Lewin didn’t make many films but he had a predilection for arty subjects, The Private Affairs of Bel Ami being preceded by adaptations of The Moon and Sixpence (1942) and The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945). All three films star George Sanders, and all feature special colour sequences when a painting is revealed. 1945 was the peak of America’s brief infatuation with Surrealism (Hitchcock had Dalí working on Spellbound at this time) so Lewin asked a number of Surrealists to take up the challenge. I was surprised to find that Stanley Spencer was one of the entrants, a name you almost never see in this company; less surprising was Ivan Albright whose painting of the decayed Dorian Gray is one of the highlights of Lewin’s earlier film. Leonor Fini was also asked to take part but she didn’t produce anything. The judges were Marcel Duchamp, Alfred J. Barr, Jr, director of the Museum of Modern Art, and art dealer Sidney Janis. Ernst won a cash prize variously reported as $2500–3000, while the other entrants received smaller sums. The paintings toured the USA and Britain during 1946–7.

As to the film, I can’t say what this is like because it’s one I’ve yet to see but Self-Styled Siren’s witty review goes into some detail. Hollywood apparently had problems with the adult subject matter (Sanders’ character is described as a sexually predatory social climber), and Lewin was forced to tone things down.

Ivan Albright.

Albright’s contribution is so frenzied and detailed it approaches psychedelia. Best seen in this large view at Flickr.