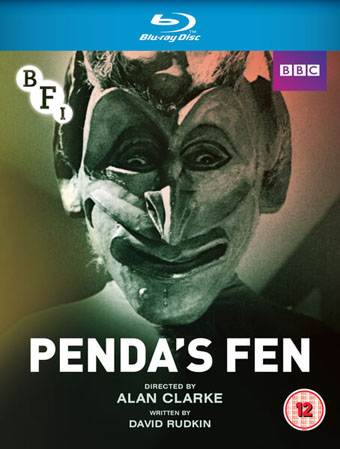

Penda’s Fen is one of the most important British television dramas of the 1970s, and would increasingly be recognised as such if the licensing problems which have dogged an official DVD release could be resolved.

That was how I ended the section about Penda’s Fen in the David Rudkin essay I wrote last year for Andy Paciorek’s Folk Horror Revival: Field Studies. The book had only been out for a couple of months when the BFI announced that Penda’s Fen would at long last be given a DVD and Blu-ray release, together with a collection of other TV dramas directed by Alan Clarke. A few months later and Penda’s Fen is now on sale, so those of us served by the European DVD region (or those with region-free players) no longer have to point people to a low-grade YouTube recording of the film.

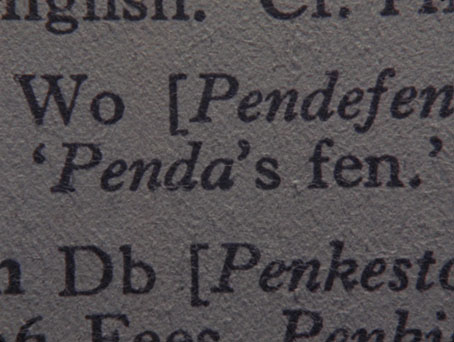

There’s no need for me to rhapsodise further about Rudkin’s work in general or Penda’s Fen in particular when I’ve already done so in the Folk Horror Revival piece, and in this lengthy post from 2010. The film itself looks the best I’ve ever seen it, slightly desaturated compared to the DVD I made of my own VHS recording (but then the BFI transfer is closer to the film elements) but with a fuller frame than in the TV screening. The one striking difference is in the title sequence which in the 1990 screening had a red cast throughout, something that’s missing from the BFI version. I don’t know why this is but the red cast always made the jump to the titles from a still shot of the Malvern hills more abrupt than it needed to be.

The extras on this release are minimal, with a short collection of interviewees apparently taken from a longer documentary about Alan Clarke’s work that will be in the Clarke collection out next month. The booklet features a new essay about the film by Sukhdev Sandhu, editor of the excellent Penda’s Fen tribute, The Edge Is Where The Centre Is. The Folk Horror Revival book is listed in the notes at the end of Sukhdev’s piece so I’m hoping this may prompt some of the people encountering Rudkin’s work for the first time to also look at his stage plays and that other sui generis television film, Artemis 81. David Rudkin, who will be 80 this year, was one of the many unique writers shunted out of the TV world by the very “entertainment barons” that Arne the playwright condemns in Penda’s Fen. I’m glad he’s lived to see this overdue reappraisal of his finest work for the medium.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Folk Horror Revival: Field Studies

• The Living Grave by David Rudkin

• The Edge Is Where The Centre Is

• Afore Night Come by David Rudkin

• White Lady by David Rudkin

• Penda’s Fen by David Rudkin

• David Rudkin on Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr