Arriving in the post this week, one of the books whose covers I was creating late last year. Work-wise, the past year has been busier than usual which means I’ve fallen behind with the logging of recent commissions. In the past few months I’ve created several album designs, more book covers, an entire book design (cover plus interior), and also been working on two bigger projects at the same time. Things have calmed down a little now so updates will be forthcoming.

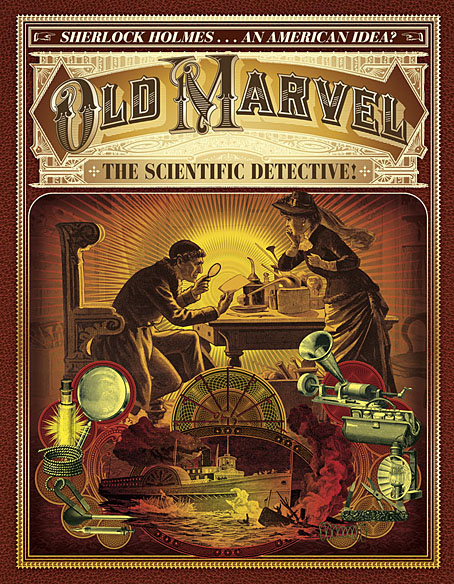

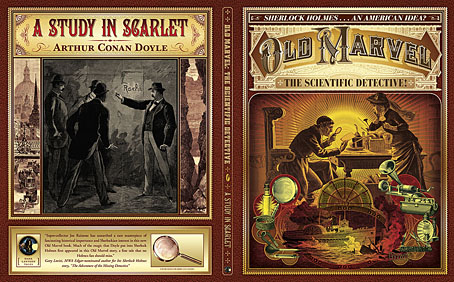

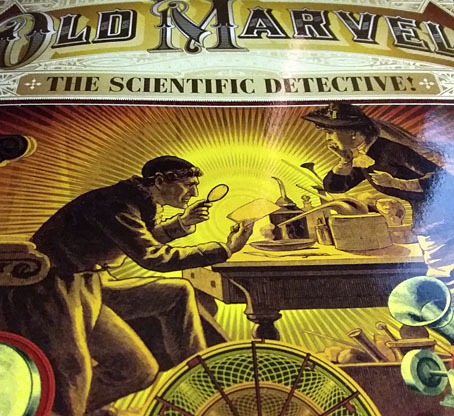

Old Marvel: The Scientific Detective is another design for Mark Williams’ Dark Lantern Tales imprint which once again resurrects a forgotten detective from pulp obscurity, and in a larger format than before. The new volume is significant for presenting a Sherlock Holmes-like character—credited to the pseudonymous “Grip”—who predates Holmes’ first appearance by three years, thereby suggesting a possible inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle. Holmes collector Joe Rainone provides the details of publication and sets out the available evidence in an informative foreword. The Old Marvel character not only pre-empts Holmes by using his scientific knowledge to solve mysteries but he also pre-empts subsequent generations of spies and investigators with the various gadgets he uses, including what may be the first fictional deployment of an Edison voice recorder. My brief for the cover was to combine the illustration of the character with a vignette showing a shipping disaster from the story plus some of the contents of the detective’s tool kit.

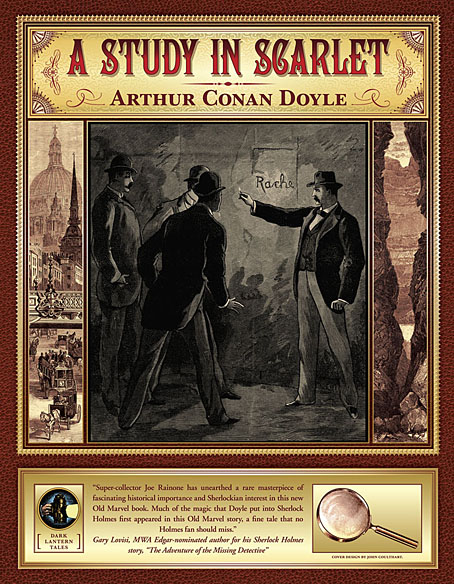

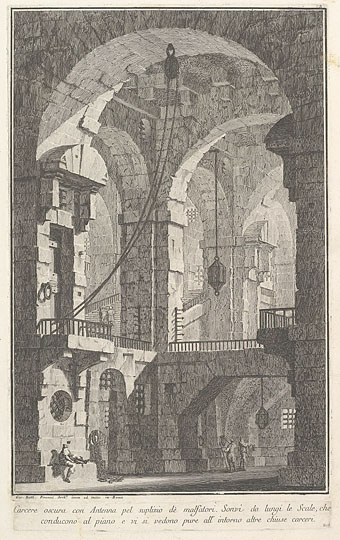

The book is actually two stories in one volume, with the second half being a reprint of the very first Sherlock Holmes novel, A Study in Scarlet. Both stories are presented as semi-facsimiles of their original US printings, together with reproductions of title pages and so on. The Holmes story is reproduced from its appearance in The Illustrated Home Guest in 1892, and includes rare illustrations one of which appears on the cover. Doyle’s first Holmes novel is the most controversial of all his stories—at least if you’re a Mormon—since this is the one where the inhabitants of Salt Lake City are depicted as a murderous religious cult. I filled out the cover with panels showing the two main story locations: a view of London via Ludgate Circus and a canyon in Utah. Finding a period engraving of St Paul’s Cathedral that remained visually interesting when narrowed down in this way took some time.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• More detectives

• The Joe Phenix Detective Series

• Illustrating Sherlock Holmes