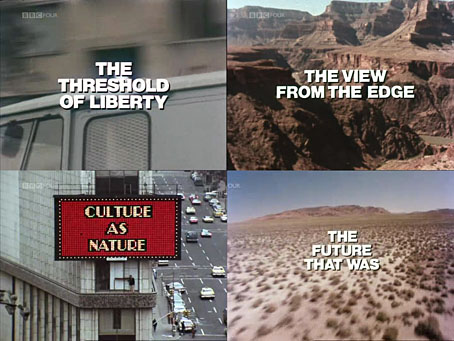

A few words of praise for The Shock of the New, Robert Hughes’ eight-part TV series about art in the 20th century. Not that it’s ever been lacking in praise—it was lauded from the outset back in 1980—but, having read the book of the series twice, then dipped back into it on regular occasions, it occurred to me recently that I’d not seen the series itself for a very long time.

If you don’t know—and is anyone today really unaware of this?—Hughes was commissioned by the BBC and his employers at TIME magazine to travel the world presenting a history of modern art from the 1880s to the end of the 1970s. The series was part of a run of costly co-productions that flattered viewers with colour television sets (still a luxury item in the UK) while engaging the intellect; Kenneth Clarke’s Civilisation, Jacob Bronowski’s The Ascent of Man and David Attenborough’s Life on Earth established the template that Hughes was required to follow. If you have the time and the money, the globetrotting is the easy part of an enterprise such as this. Much more difficult is making sense of the increasingly fragmented development of art in a century of two world wars and rapid technological change. Hughes did this by selecting a single route of evolution for each episode, often missing out significant artists or entire movements, then winding back the clock in the following episode to trace a different route that included the neglected names. Some of them, anyway. In the introduction to the book he admits the difficulty of trying to summarise a century of complex aesthetic activity and philosophy in a mere eight hours. The book is inevitably much more thorough, making the TV series seem like a sketch beside it; but there are good sketches and bad ones, and this one is exceptional.

Hughes had an enviable talent for lucid explanation, an ability to tell you what was important about an artist or an idiom or an artistic development in a few simple, memorable sentences, free of jargon or the obfuscation that bedevils art criticism. This is best seen in his collected reviews from TIME magazine, Nothing if Not Critical (1991), which offers bite-sized appraisals of individual artists or group shows, from the Renaissance to the present day. Difficult to do well when you’re limited to a few hundred words, near impossible when you have to explain something using a minimum of words while simultaneously talking to a camera and walking down a busy Paris street. Some of his statements, like the following one, have been lodged in my memory for years:

A Rodin in a parking lot is still a misplaced Rodin, but this in a parking lot is just bricks.

“This” being Carl Andre’s oblong of 120 firebricks, Equivalent VIII, a minimalist sculpture that caused a huff of outrage from the philistine British tabloids in the 1970s. Hughes’ comment occurs when he examines the way that galleries in the same decade became frames for creations such as Andre’s, works that wouldn’t be recognised as art without the building they were situated in.

The explication is very familiar but I’d forgotten about all the foreign travel. This seems profligate at times although it’s only the same as David Attenborough flying to a remote jungle to film a lemur or a lizard. Paintings and sculptures seen in their natural habitats, as it were, together with the locations that inspired them: van Gogh’s Arles, Matisse’s Côte d’Azur, de Chirico’s Turin, and so on. One of the axioms of Hughes’ criticism, repeated here as elsewhere, was that art has to be studied in situ, not appraised via mediated representations, whether that means halftone dots in a book, 16mm film delivered by cathode ray tube, or a gallery website. It’s an attitude I sympathise with even though I don’t visit galleries very often. Sculptures have a physical presence that doesn’t reproduce at all, while paintings are more subtle or more dramatic or more detailed or more dimensioned when you’re standing in front of them. Piranesi’s prints are big; William Blake’s paintings are very small; Max Ernst’s engraving collages are not only smaller than you expect but they’re also toned by age; Picasso’s canvases reveal the direction his brush was travelling when he painted a line in a single stroke…

Hughes and Complex One, an artwork that few people are allowed to visit.

Something else I’d forgotten about was the artist interviews in the later programmes, especially those with land artists Michael Heizer and Walter De Maria. The final episode in the series examines the collapse of the idea of the avant-garde, with land art being presented as work that can’t be bought by wealthy collectors or appropriated by mass media. Hughes treks into the Nevada desert to see Heizer’s Complex One which at the time was all that existed of the massive site known today as City; Walter De Maria is seen walking through The Lightning Field in New Mexico accompanied by synthesizer chords from Jean-Michel Jarre’s Equinoxe. Electronic music abounds in this series, from Peter Howell’s clanging Radiophonic theme, to extracts from albums by Tangerine Dream and Brian Eno, Music For Films being a popular choice with TV producers at the time. It’s notable that the phrase “the shock of the new” only occurs once, near the very end, possibly as a capitulation to the BBC who Hughes says chose the title for him. In a later book, Things I Didn’t Know: A Memoir (2006), you’ll find another of those memorable statements:

Some new works of art have values of some kind or another. Others, the majority, have little or none. But newness as such, in art, is never a value.

I’m following this with a re-viewing of Hughes’ multi-part American Visions (1996), a history of American culture that I’ve not seen since its first broadcast. The Shock of the New is all over YouTube if you require it, also at the Internet Archive. The series took three years to create and was broadcast at 8:00pm on Sunday evenings to an audience of millions. They really don’t make them like this any more.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Robert Hughes, 1938–2012

• Land art