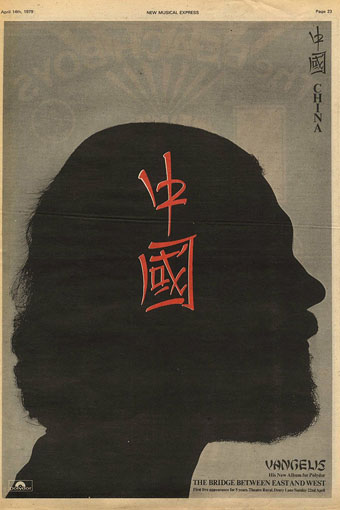

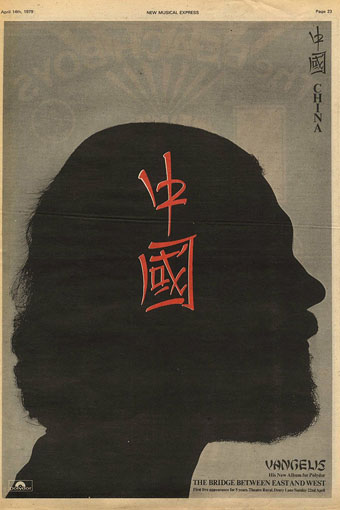

NME ad for the China album, April 1979. Via.

Farewell, Captain Nemo. In the past I’ve been known to describe Blade Runner as a very large and very expensive music video for a Vangelis album. (I mention this because so many of the headlines about the late musician are referring to Ridley Scott’s masterpiece and that boring film about athletes in big shorts.) Blade Runner is rather more than a music video, of course, but the viewpoint is a useful one if you’ve watched the damned thing so many times in so many different versions and formats that any re-viewing is almost enough to have you mouthing the dialogue along with the characters, like Charlton Heston in The Omega Man watching Woodstock for the 100th time. Vangelis recorded almost 40 albums under his own name, and many more as collaborations; he was much more than a soundtrack composer, which isn’t something you can always say about soundtrack composers.

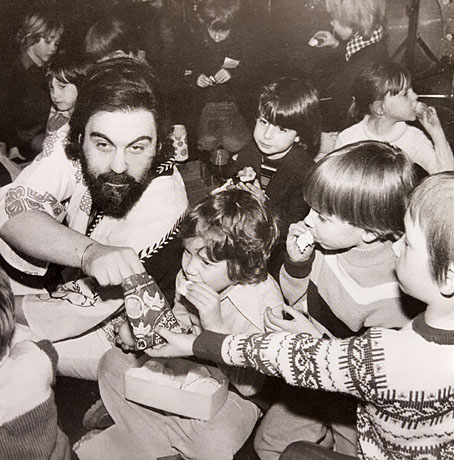

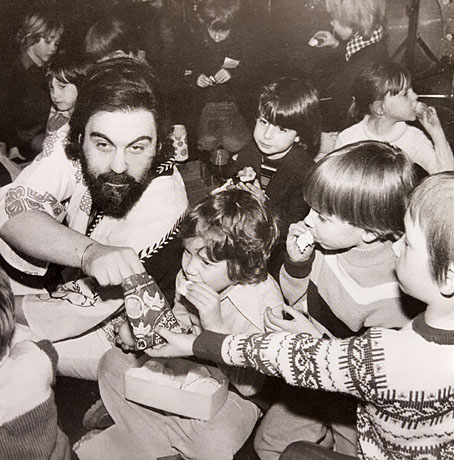

He liked Outer Spacers. The composer accepts a chutney-flavoured cosmic snack, circa 1979.

All the same, film and score are so inextricably connected it’s impossible to imagine Blade Runner with any other soundtrack, just as it’s impossible to imagine Sergio Leone’s “Dollars” trilogy without Ennio Morricone’s whip-cracks, bells and whistles. The thing is—and this is the reason for my facetious music-video comment—Morricone’s Western scores were tailored to their content in a way that Blade Runner‘s music wasn’t at all. If Blade Runner had never been made, many of those musical cues would have worked perfectly well as another Vangelis solo album. Three of the albums he made before Blade Runner that feature his beloved Yamaha CS-80 keyboard—Spiral, Opera Sauvage and China—contain elements that coalesce in the film score; there you’ll find the same synthesizer timbres, filter sweeps, percussive crashes, Fender Rhodes solos and musical pastiche (Chinese rather than Middle Eastern). Another album, See You Later, is a patchy collection of songs, instrumentals and spoken-word pieces but it does contain the original version of Memories Of Green. That melancholy piano and all the bleeps, sirens and metallic square-waves that seem so intrinsic to the shots of Deckard moping around his apartment were recorded two years before the film soundtrack. For years I’ve been urging anyone who only knows Vangelis from his most famous soundtracks to listen to those earlier albums, especially Opera Sauvage (itself a soundtrack for a TV series that nobody ever mentions) and China.

Speaking of China, here’s a short film of Vangelis in his studio miming to pieces from the album. And I’m pleased to find that the Spanish TV film showing him in 1982 improvising on his CS-80 has resurfaced again. I linked to a copy years ago but YouTube is a useless archive so it vanished soon after. This clip seems to be better quality as well.

• “Vangelis wasn’t just a film composer – he blew apart the boundaries of pop”

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Blade Runner vs. Metropolis

• Synthesizing

• Salvador Dalí’s apocalyptic happening