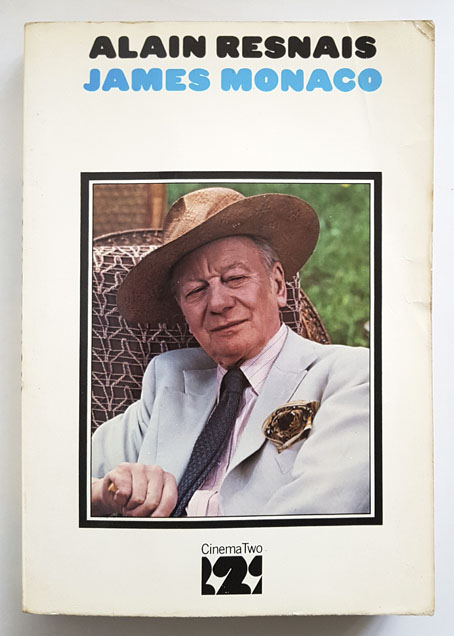

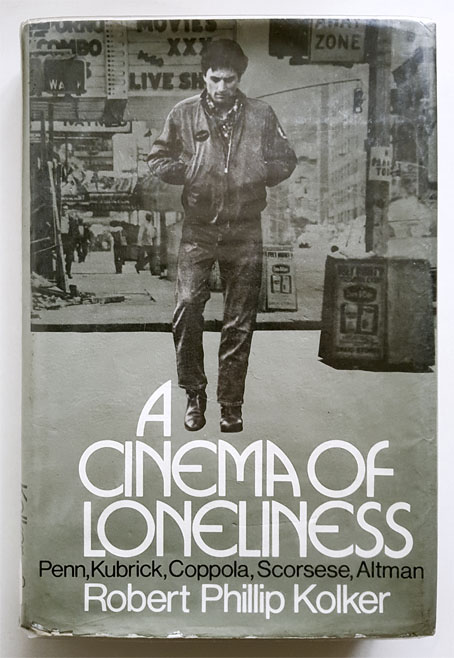

After watching Providence again I yielded to further temptation and ordered a copy of the book that first introduced me to the film itself and to the Resnais oeuvre as a whole. I’d been itching for some time to re-read James Monaco’s study to see if it was as good as I remembered. In many ways it’s a lot better, especially now that I’ve been able to see most of the films he examines. Alain Resnais was published in 1978 which means it only covers the first third of the director’s filmography, but all of these films were mysterious and intriguing to me in 1983, a period when I was busy looking for items of interest on the art and film shelves at Manchester’s Central Library. The other key discovery in the film section was A Cinema of Loneliness by Robert P. Kolker, the book that introduced me to Martin Scorsese’s films at a time when most of them were difficult to see. Kolker also deepened my interest in Robert Altman and Arthur Penn, while replacing my flagging interest in science-fiction cinema with a new curiosity about film noir.

An essential text, and a better book about American cinema in the 1960s/70s than the gossip-filled pages of Easy Riders, Raging Bulls.

The science-fiction interest may have been flagging by this point but it was actually a book about the genre that alerted me to Alain Resnais in the first place, as I noted here. Je t’aime, Je t’aime is the Resnais film that involves a time-travel experiment but descriptions of the mysteries and formal elegance of Last Year at Marienbad were of greater interest, even more so when I found a copy of Alain Robbe-Grillet’s screenplay. The films themselves, however, remained frustratingly out of reach. One of the things I really don’t miss about the 1980s is being able to read about films such as these, or others like El Topo (or Taxi Driver, or Night Moves, or Performance…), while wondering when I’d ever get to see them.

Monaco’s book provides an overview of the first few decades of Resnais’s career, from his early start in the 1940s (two lost Surrealist experiments are mentioned), to the documentaries of the 1950s, ending with Providence in 1977. Much of the detail originates from conversations with Resnais himself, and while Monaco doesn’t avoid interpretative speculation he’s never tiresomely academic. One of the more valuable chapters concerns some of the films that Resnais was trying to make in the 1970s. (And one of the minor revelations is reading about a director with his reputation struggling to get his projects financed.) The only detail I remembered about the unmade films was his plans to direct a script he commissioned from Stan Lee. That’s Smilin’ Stan Lee of Marvel Comics fame, inventor of all those vapid superheroes. Stan Lee working with Alain Resnais sounds like some kind of sarcastic postmodern joke but Monaco says that The Monster Maker would have been “a grand and exuberant compendium of all the cliches of the B movie which have thrilled and enthralled audiences for fifty years: science fiction, sentimental romance, horror, revenge, and cataclysm…” We’ll never know what this may have been like, and maybe that’s for the best. Monaco refers to the director’s lifelong love of comics—one of the Resnais films of the 1980s, I Want to Go Home, was about a comic artist—but I still find the Stan Lee project a step too far, especially when there were so many great comic artists and writers working in France in the 1970s. Resnais wasn’t unaware of these; in my post about Je t’aime, Je t’aime I noted the presence of a Druillet drawing on the wall of Claude’s apartment. More promising than The Monster Maker was a script about the Marquis de Sade written with Grove Press boss Richard Seaver, and a tenuous plan to make a film about HP Lovecraft with William Friedkin producing. This apparently fell through when Friedkin left to direct The Exorcist but the interest in Lovecraft further reinforces the Lovecraftian suggestions in Providence, something that Monaco says were explored in a review by Richard Corliss for New Times magazine. I’ve not been able to find this online, unfortunately.

All of which reminds me that I’ve still not seen Resnais’s first feature, Hiroshima Mon Amour, nor any of the post-Providence films with the exception of Smoking/No Smoking which I saw on TV years ago and didn’t enjoy very much. The latter is an odd thing for Brits to watch, being based on an Alan Ayckbourn play which means it concerns a cast of typical middle-class English types (with names like “Celia Teasdal”) except that here they’re all played by French actors speaking their native language. This makes for distracting viewing but I now feel ashamed for not having given it more of a chance. It’s one more film to go looking for in the future.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Providence on DVD

• Art on film: Je t’aime, Je t’aime

• Art on film: Providence

• Marienbad hauntings

• Les Statues Meurent Aussi, a film by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais

• Toute la mémoire du monde, a film by Alain Resnais