Dance of Flames (1925) by Hayami Gyoshu.

Happy new year. 02025? Read this.

Oben und Links (1925) by Wassily Kandinsky.

Aus Torbole (1925) by Stephanie Hollenstein.

Coronilla (1925) by Paul Nash.

Demonstration (1925) by Franz Wilhelm Seiwert.

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Dance of Flames (1925) by Hayami Gyoshu.

Happy new year. 02025? Read this.

Oben und Links (1925) by Wassily Kandinsky.

Aus Torbole (1925) by Stephanie Hollenstein.

Coronilla (1925) by Paul Nash.

Demonstration (1925) by Franz Wilhelm Seiwert.

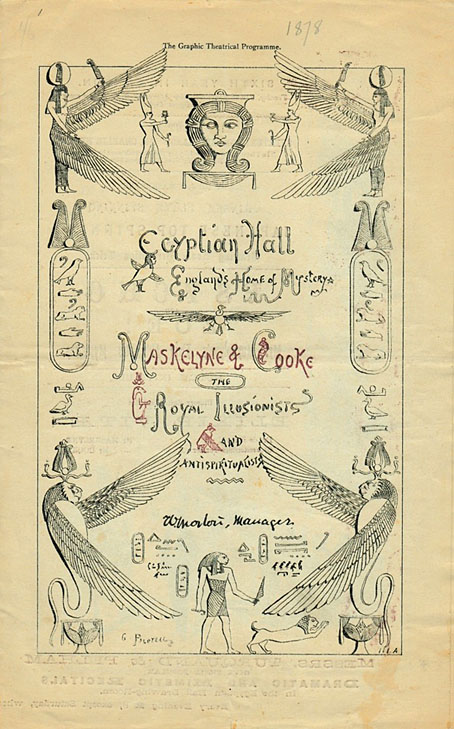

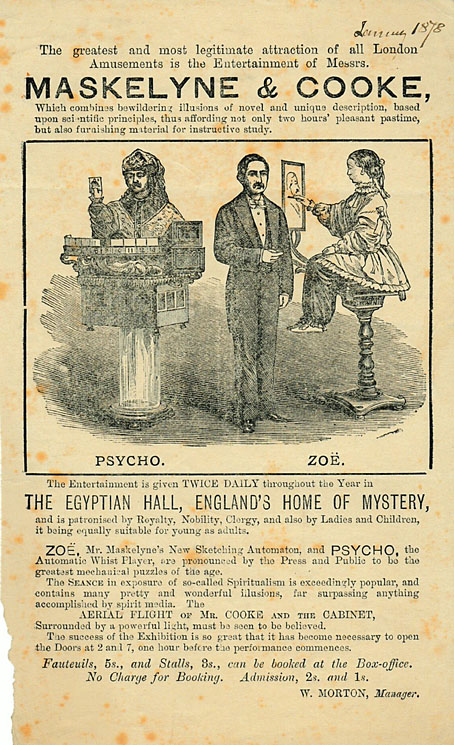

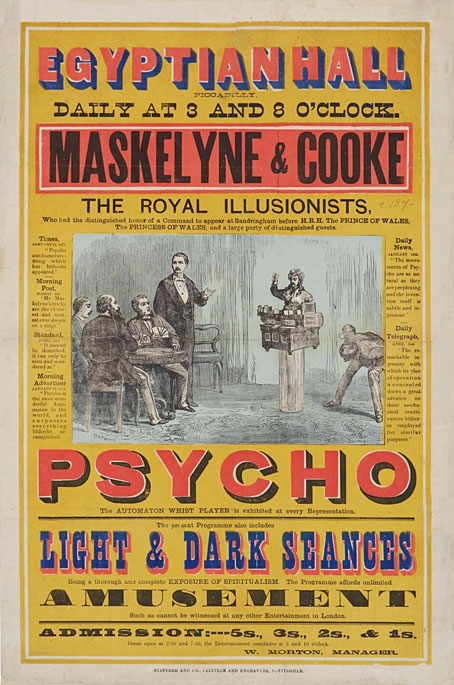

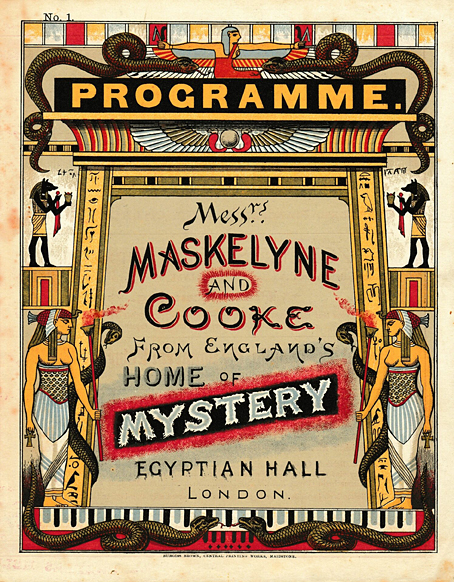

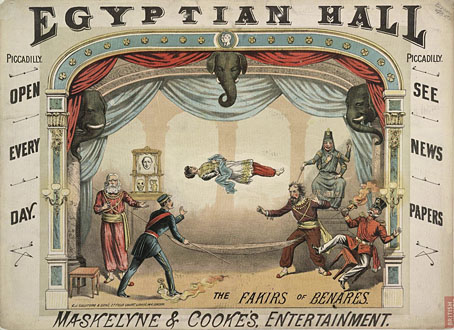

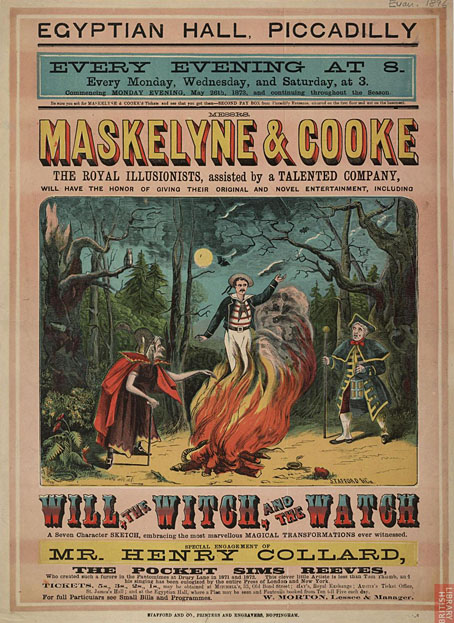

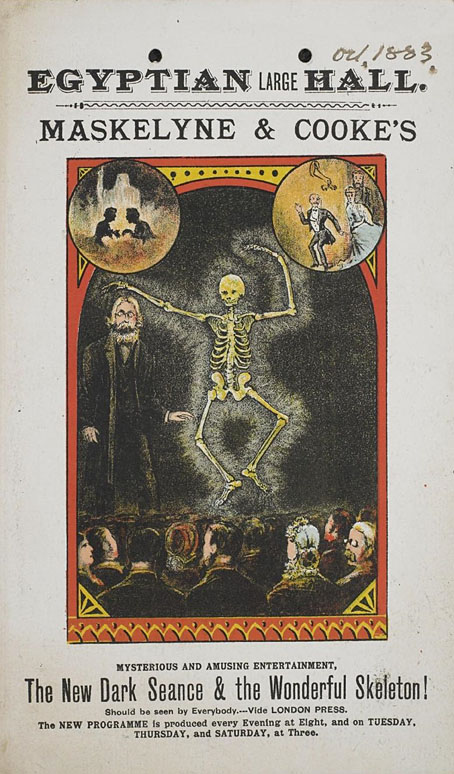

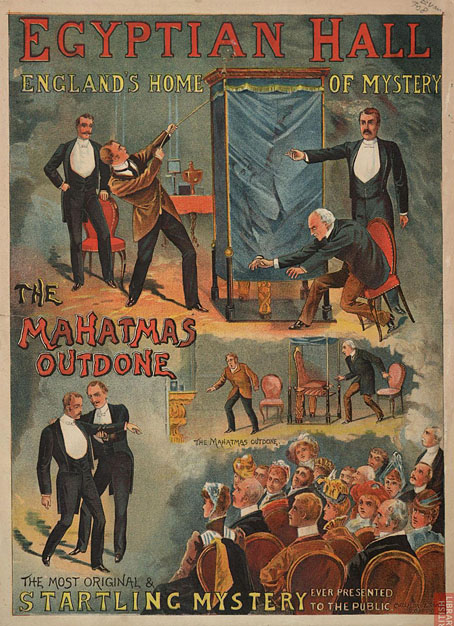

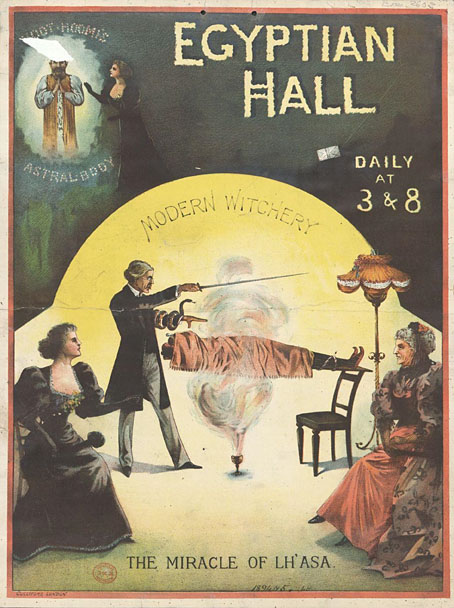

The Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, circa 1896.

The Egyptian Hall, the front of which forms one of the most noticeable features on the southern side of Piccadilly, nearly opposite to Bond Street, was erected in the year 1812, from the designs of Mr. G. F. Robinson, at a cost of £16,000, for a museum of natural history, the objects of which were in part collected by William Bullock, F.L.S., during his thirty years’ travel in Central America. The edifice was so named from its being in the Egyptian style of architecture and ornament, the inclined pilasters and sides being covered with hieroglyphics; and the hall is now used principally for popular entertainments, lectures, and exhibitions. Bullock’s Museum was at one time one of the most popular exhibitions in the metropolis. It comprised curiosities from the South Sea, Africa, and North and South America; works of art; armoury, and the travelling carriage of Bonaparte. The collection, which was made up to a very great extent out of the Lichfield Museum and that of Sir Ashton Lever, was sold off by auction, and dispersed in lots, in 1819.

Here, in 1825, was exhibited a curious phenomenon, known as “the Living Skeleton,” or ‘the Anatomic Vivante,” of whom a short account will be found in Hone’s “Every-Day Book.” His name was Claude Amboise Seurat, and he was born in Champagne, in April, 1798. His height was 5 feet 7½ inches, and as he consisted literally of nothing but skin and bone, he weighed only 77¾ Ibs. He (or another living skeleton) was shown subsequently—in 1830, we believe—at “ Bartlemy Fair,” but died shortly afterwards. There is extant a portrait of M. Seurat, published by John Williams, of 13, Paternoster Row, which quite enables us to identify in him the perfect French native.

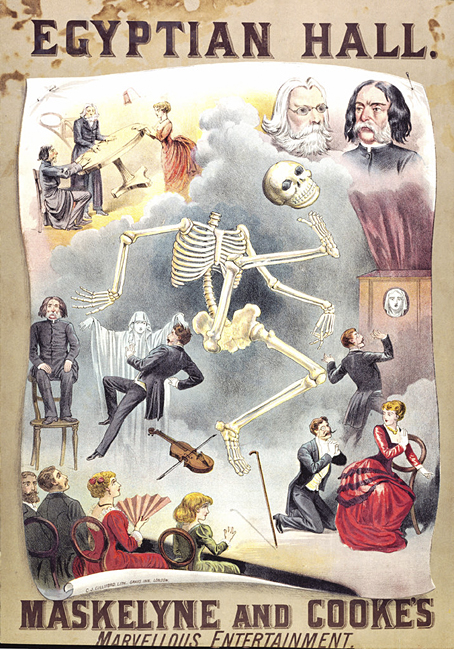

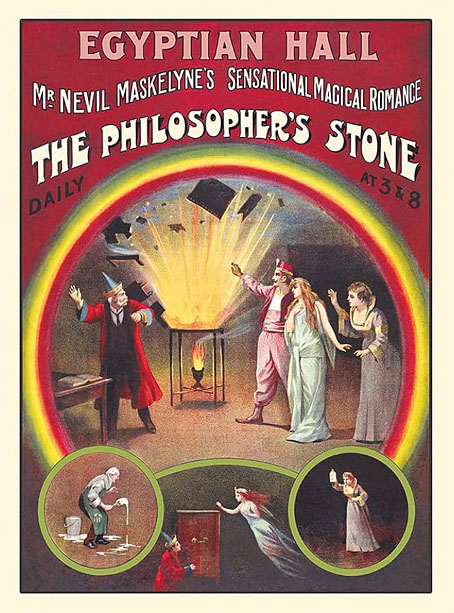

Of the various entertainments and exhibitions that have found a home here, it would, perhaps, be needless to attempt to give a complete catalogue; but we may, at least, mention a few of the most successful. In 1829, the Siamese Twins made their first appearance here, and were described at the time as “two youths of eighteen, natives of Siam, united by a short band at the pit of the stomach—two perfect bodies, bound together by an inseparable link.” They died in America in the early part of the year 1874. The American dwarf, Charles S. Stratton, “Tom Thumb,” was exhibited here in 1844; and subsequently, Mr. Albert Smith gave the narrative of his ascent of Mont Blanc, his lecture being illustrated by some cleverly-painted dioramic views of the perils and sublimities of the Alpine regions. Latterly, the Egyptian Hall has been almost continually used for the exhibition of feats of legerdemain, the most successful of these—if one may judge from the “run” which the entertainment has enjoyed—being the extraordinary performances of Messrs. Maskelyne and Cooke.

From Old and New London: A Narrative of its History, its People and its Places, Vol. 4 (1887) by Walter Thornbury

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Martinka & Co. catalogue, 1899

• Learned Pigs and other moveables of wonder

• Magicians

• Hodgson versus Houdini

Monstrum in animo (1955) by Yves Laloy.

• This week’s obligatory Bumper Book of Magic links: Alan Moore World has more of my ongoing comments about the creation of the book, while Séamas O’Reilly talked to Alan about the book itself and its connections with The Great When. The latter piece lowered my already low opinion of the late Genesis P-Orridge.

• At Timeless: A reprint of Bright Lights and Cats With no Mouths by John Balance. Still in print is The Cupboard Under the Stairs, a selection from JB’s notebooks.

• If you enjoy sleight-of hand magic—and I most certainly do—then Ricky Jay & His 52 Assistants (1996) is 58 miraculous minutes by a master of the art.

• Mixes of the week: Winter Solstice 6 at Ambientblog; a mix for The Wire by Rafael Toral; and Reflection on 2024 at a Strangely Isolated Place.

• “Whatever the reason, there is something sorrowful about the disposal of art, whatever the perceived quality,” says Steven Heller.

• New music: The Path Of The Elder Ones by Nerthus.

• Bright Lights (1959?) by Wade Curtiss & The Rhythm Rockers | Bright Lights, Big City (1961) by Jimmy Reed | I Want To See The Bright Lights Tonight (1974) by Richard & Linda Thompson

It’s unlikely that anyone will be stuck for anything to watch during the next few days but you could do worse than spend an hour with this documentary about the music of composer György Ligeti. I’ve mentioned this several times over the years, it’s one of my favourite films by the late Leslie Megahey, my favourite director of TV arts documentaries. All Clouds are Clocks was made for the BBC’s long-running Omnibus arts strand, and is unique among all the films made for that series in being broadcast twice (in 1976 and 1991), with the second broadcast appending new footage to the original film.

The film as a whole is fairly simple by today’s standards, an interview with the composer in his studio intercut with extracts from Ligeti recordings and performances. After years of documentaries filled with hyperactive editing and inane comments from celebrity interviewees Megahey’s straightforward approach is a considerable relief. You have the music, and you have the composer talking about the music; that’s it. Especially commendable is that there’s no mention at all of the use of Ligeti’s recordings as film scores. If the BBC made a film like this today (which they wouldn’t in any case) the first thing you’d see would be clips from Stanley Kubrick films.

As is often the case in Megahey’s documentaries, the director himself is the narrator, and in this one he’s also the off-screen interviewer as he was in his celebrated Orson Welles documentary. The illustrative episodes include melting plastic clocks, the slow awakening of a wooden puppet, and a performance of Poème symphonique, the composition which requires the priming and operation of 100 metronomes. Ligeti comes across as good-humoured and approachable, a serious artist but one whose general demeanour never seems loftily superior to ordinary human concerns the way Stockhausen often did. Ligeti’s manner confirms the sense of humour behind compositions like the one for the metronomes, and even more so in the choral/orchestral work Nouvelles Aventures. The latter is shown in an extract from a filmed performance at the Roundhouse, London, in 1971, a concert conducted by Pierre Boulez which provokes raucous laughter from the audience when a tray loaded with crockery is hurled into a bin. There’s humour of a blacker variety in the 1991 section which includes a description of Ligeti’s “anti-anti-opera”, Le Grande Macabre, based on a play by Michel de Ghelderode. This was Ligeti’s only operatic work, and I think it may be the only Ligeti composition I still haven’t heard in full. Most stagings are a riot of grotesque costuming and set design (the setting is a place called “Breughelland”) so it obviously needs to be seen as well as heard.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• György Ligeti, a film by Michel Follin

• Leslie Megahey, 1944–2022

• Le Grand Macabre

• Leslie Megahey’s Bluebeard

• Metronomes

The Breath of Creation (c. 1926–34) by Olga Fröbe-Kapteyn.

• At Wormwoodiana: “…Gresham was well-read enough to know that while magic can be more than a MacGuffin in a fantasy story, neither fantasy nor thriller fiction lets magic unsettle readers much. […] Even when it is good, the supernatural is never safe in a Williams story. Not conventional fantasy by half.” G. Connor Salter on William Lindsay Gresham’s enthusiasm for Charles Williams’ novels.

• At Harper’s Magazine: Christopher Tayler reviews Lawrence Venuti’s translations of Dino Buzzati’s Il deserto dei Tartari (now titled The Stronghold) which was published last year, and The Bewitched Bourgeois: Fifty Stories which will be out in January.

• Dennis Cooper’s favourite fiction, poetry, non-fiction, film, art, and internet of 2024. Thanks again for the link here!

• The Approach to J.L. Borges: A Borgesian pastiche in homage to the creator of Ficciones by Ed Simon.

• “HP Lovecraft meets Fafhrd and The Grey Mouser”: an essay from 1992 by Fritz Leiber.

• Can performing live on The Old Grey Whistle Test in January, 1974.

• DJ Food says “Let’s have some psychedelia”.

• RIP Zakir Hussain.

• Creation Dub 1 (1977) by Lee Perry & The Upsetters | Threat To Creation (1981) by Creation Rebel/New Age Steppers | Theme from ‘Creation’ (1992) by Brian Eno