An alphabet designed by Ben Griffiths. Via.

• “From the cellular to the galactic, via Paleolithic cave markings to the trace impressions left by drone photography on our mind’s eye, incorporating dancing plagues, communist psychedelic witches, hyper-sexual fungi, chthonic descents, and skyward ascents, The Neon Hieroglyph weaves together a series of painterly and poetic considerations on a feminized history of the rye fungus Ergot, the chemical basis of LSD.” Coming soon from Strange Attractor: The Neon Hieroglyph, a book, LP and folio of prints by Tai Shani.

• “3rd From The Sun was the last album of Chrome’s imperial phase, and it cemented their status as one of the most inhuman and superhuman rock bands that America ever produced. More people need to recognize.” Agreed. (previously)

• “People often say, ‘How can you be so disciplined?’ It’s easy. Otherwise, I would have to go work for somebody else!” John Waters (again). Also here.

I’ve always thought that literature should be entertaining as well as instructive—a very old-fashioned idea but one that I adhere to. When I set out to write in this way—particularly in this way, a political way, if you want to call it that—I intend to make a donation, to try to give something. There doesn’t seem to me to be any point in giving more misery or exacerbating unhappiness through some kind of hyper-intellectual, pyrotechnical writing about unhappiness and the shit that we all find ourselves in. That’s been done plenty. I think first of all that it doesn’t need to be done any more and second of all there’s a kind of reactionary aspect to it which is that the emphasizing of misery without any anti-pessimism, as you put it, would be simply seduction into inactivity and political despair. In other words, to do politics at all on any level, especially on a revolutionary or on an insurrectionary level, there has to be some anti-pessimism—I won’t say optimism because that sounds so fatuous, futile; but anti-pessimism is a nice phrase. And there’s a deliberate attempt at that in the writing. Then again it’s a matter of my personality, I guess, inclined towards the notion of the healing laugh to some extent. We have an anarchist thinker in America, John Zerzan, who wrote an essay against humour which maybe is one of the things I was reacting against. Even if irony is counter-revolutionary which I think it might be to a certain extent I don’t see any way in which you could say that laughter itself is counter-revolutionary. This doesn’t make any sense to me unless you mean to get rid of language and thought altogether, which is just another form of nihilism. So as long as you’re going to accept culture on some level you’re certainly going to have to accept humour. And as long as you’re going to have to accept humour you might as well see humour as potentially revolutionary.

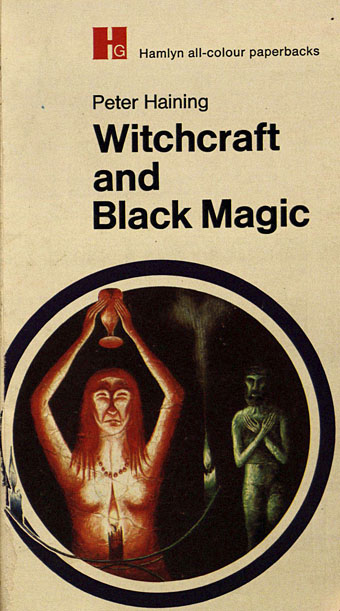

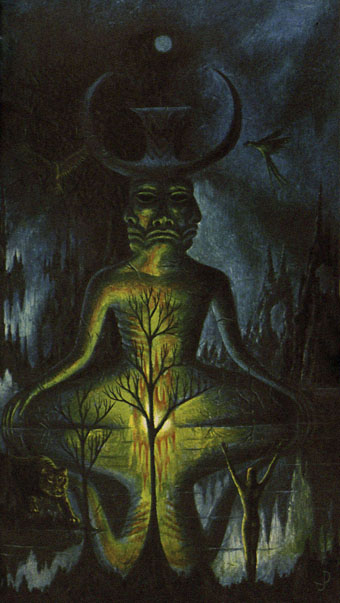

Peter Lamborn Wilson aka Hakim Bey, who died last month. Many of Wilson’s writings are available at The Anarchist Library. From 2008: A poem for Leonora Carrington

• “It’s such a fundamental question,” says Midori Takada, “why do humans need to make rhythm, and the space that structure creates?”

• “14 Warning Signs That You Are Living in a Society Without a Counterculture” by Ted Gioia.

• A trailer for Earwig, the new film from Lucile Hadzihalilovic, based on a story by Brian Catling.

• New music: Aura by Hatis Noit, and Warmth Of The Sun by Pye Corner Audio.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Spotlight on…SE Hinton Rumble Fish (1975).

• “Hear tracks from the 1980s Peruvian electronic underground”.

• Intermittent Eyeball Fodder at Unquiet Things.

• West Tulsa Story (1983) by Stewart Copeland | Kála/Assassins Of Hakim Bey (1997) by Coil | Neon Lights (2000) by Señor Coconut Y Su Conjunto