The Dynamiter: More New Arabian Nights (Longmans, London; 1914).

I’ve mentioned before that I’m a sporadic collector of the Tusitala Edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s works, 35 small blue volumes published by Heinemann, London in 1924. I’ve found 15 of them so far and today turned up another one, volume 25, Virginibus Pueresque and Other Essays in Belles Lettres. Most of the ones I’ve collected are later reprints and this is no exception, being a sixth edition from 1928. The popularity of the series and the many reprint editions is the main reason they still appear with such frequency. Another reason is that these small pocket books, which were very common before and after the First World War, were well-made and have easily outlasted the first generation of paperbacks that eventually replaced them. I’d have no trouble ordering a complete set of the Stevensons from a book dealer but prefer to let chance find new additions. Given the dearth of good secondhand shops this is becoming increasingly difficult.

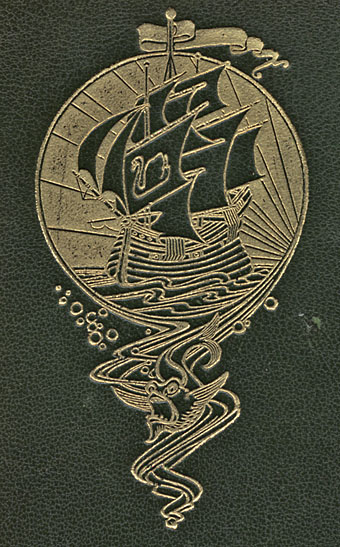

Also in today’s book haul was an earlier Stevenson, The Dynamiter: More New Arabian Nights, in a rather battered leather binding from 1914. I bought it almost solely for the Art Nouveau motif on the cover whose ship suits the author of Treasure Island but doesn’t really fit with the London setting of this particular book. I seem to recall having seen this design before which means it’s probably part of a uniform set like the Tusitala Edition, each volume of which bears a palm tree design on the spine and the signature of RLS blocked on the front board.

The only number of the Tusitala Edition I have in a leather binding is this book’s precursor, volume 1, New Arabian Nights. The Dynamiters is a collection of linked stories that Stevenson wrote with his wife, the Arabian Nights conceit being an attempt to transplant the telling of tall tales from medieval Baghdad to Victorian London. The dynamiters are a group of inept terrorists whose comic exploits were based on the real Fenian bombings that took place in London in the 1880s. A later attempted bomb attack on the Greenwich Observatory inspired the unsuccessful anarchists in Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent. Whatever some contemporary commentators might have us believe, terrorist attacks in cities are nothing new at all, only in Stevenson’s day they were labelled “dynamite outrages”. Stevenson dedicates his stories to the police officers charged with protecting the capital and apologises for making light of a serious matter. I have to wonder what he would have made of modern Baghdad being plagued by dynamite outrages on such a regular basis. And I also wonder how much real dynamite many of these Longmans’ books might have encountered, having been published just in time to be packed in the kit of soldiers going to the Western Front.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The book covers archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Chronicles of Clovis and other sarcastic delights