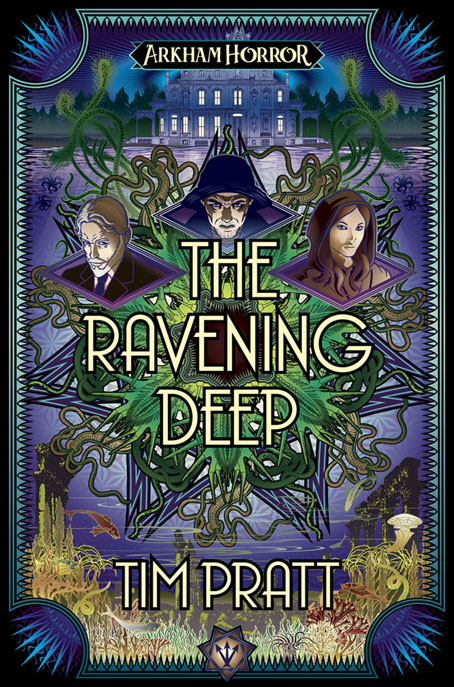

L. Frank Baum: Queen Zixi Of Ix (Or The Story Of The Magic Cloak) Read By Ray Bolger (1977).

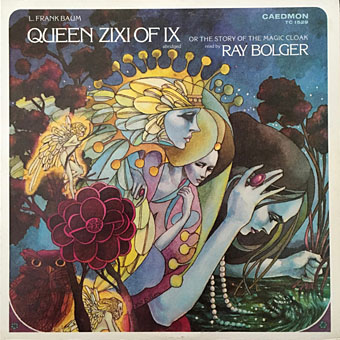

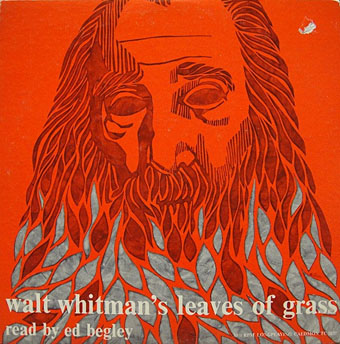

There’s a lot you could write about illustrators Leo and Diane Dillon. They were very prolific for a start, creating many book covers and interior illustrations in a variety of styles and different media. They also maintained a long-running association with Harlan Ellison whose praise for the pair was never less than fulsome. Like Bob Pepper and other versatile illustrators, they created art for album covers as well as books, with regular commissions from Caedmon Records, a label that specialises in spoken-word recordings.

Walt Whitman’s Leaves Of Grass Read By Ed Begley (1959).

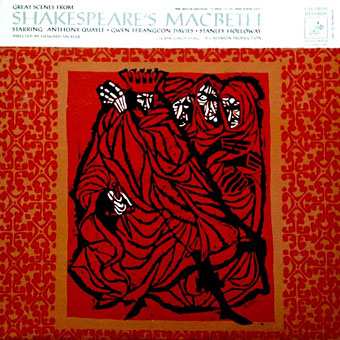

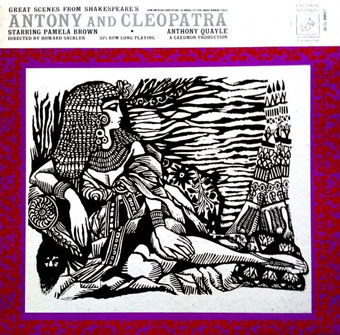

During the time the Dillons were working for Caedmon most of the label’s releases were on vinyl, a format that tended to restrict the readings to poetry, short stories or extracts from novels and plays. The format was limited for writers and listeners but beneficial for book illustrators, giving them a larger canvas to work on. These examples are a small selection of the Dillons’ output, more of which may be seen at Discogs. Not everything on Caedmon looked this good. I used to own the David McCallum reading of The Dunwich Horror, an album whose cover art was so amateurish it might have been drawn by Wilbur Whateley himself. The Dillons’ cover for The Rats in the Walls is much better, with a gnawing figure that resembles the woodcut-style illustrations the pair created for Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions anthologies. I’ve never read anything about the Dillons’ techniques so can’t say whether their woodcut style was a product of actual wood engraving rather than linocut, a more convenient medium. I’d guess the latter since the end results look pretty much the same, but if anyone knows the answer then please leave a comment.

The Stories Of Kafka Read By Lotte Lenya (1962).

Great Scenes From Shakespeare’s Macbeth: Anthony Quayle, Gwen Ffrangcon-Davies, Stanley Holloway (1962).

Great Scenes From Shakespeare’s Antony And Cleopatra: Pamela Brown And Anthony Quayle (1963).