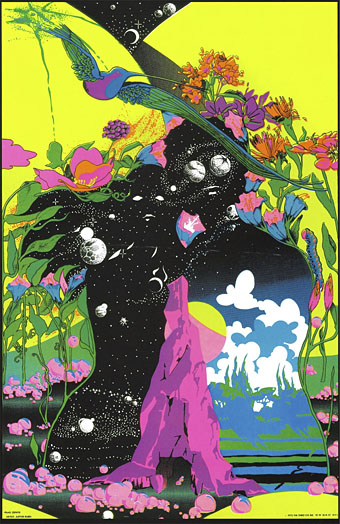

Art by Mosnar Yendis.

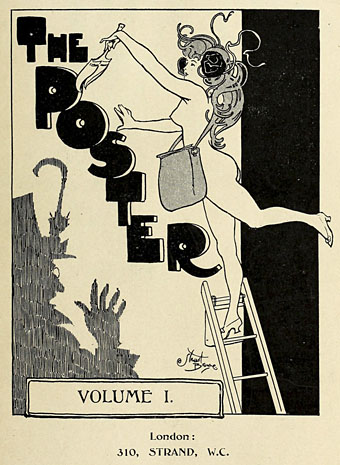

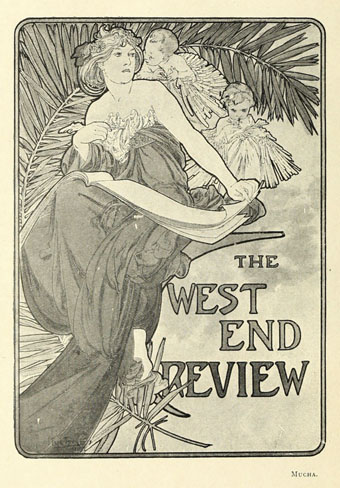

This is the kind of thing I love to find: five volumes of a British magazine devoted to poster artists and their creations being published at a time—1898 to 1900—when the Art Nouveau style was spreading its convolvulus-like tendrils across Europe. Poster art is a predominantly commercial medium which means the articles are more concerned with the mechanics of the business than you’d find in a rival publication such as The Studio. Artists (male and female) are interviewed, trends are analysed, there are at least two features examining what the magazine calls “cribbing” (or one poster swiping from another), also a profile of the “Aerograph”, an early model of that fixture of 20th-century illustration, the airbrush. And when it comes to illustration, The Poster is as much concerned with the practice as with the posters themselves when so many of the people featured were also illustrating books or magazines. The publishers’ admiration of Aubrey Beardsley’s work is shown in the amount of mentions he receives as well as the articles they run. Beardsley had died a few months before the magazine was launched but his influence and reputation was firmly established by this time.

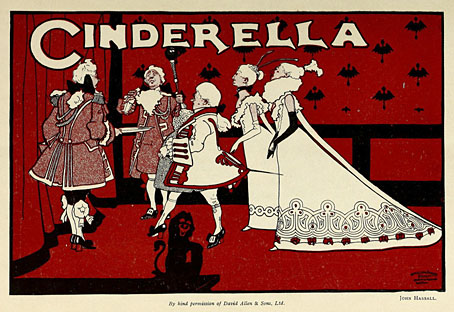

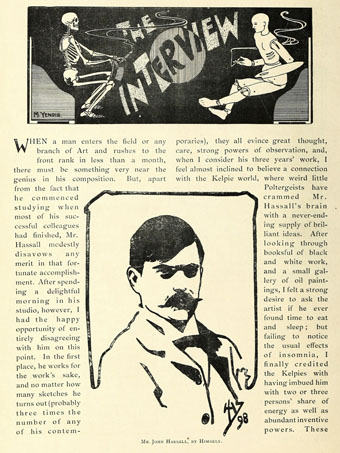

All five volumes of The Poster contain a wealth of pictorial material so, with the exception of the Sidney Sime drawing, the examples shown here are from the first volume alone. Below you’ll find two illustrations by Charles Robinson pastiching the Beardsley style which the magazine claims are the best imitations they’ve seen, a debatable opinion but I hadn’t seen the drawings before. The first volume also includes an interview with illustrator John Hassall, a name that few people today would recognise, while those that do may confuse him with similarly-named musicians. Hassall’s work is still known to many Britons, however, via his “Jolly Fisherman“, a poster for the Great Northern Railway promoting the seaside resort of Skegness. The Cinderella picture below is one of many Hassall pieces in the magazine.

• The Poster, Volume 1

• The Poster, Volume 2

• The Poster, Volume 3

• The Poster, Volume 4

• The Poster, Volume 5

Continue reading “The Poster: An Illustrated Monthly Chronicle”