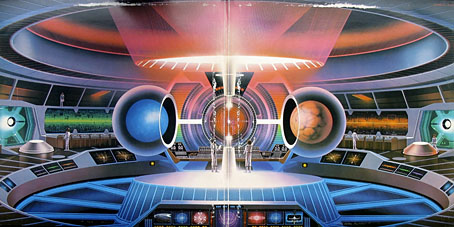

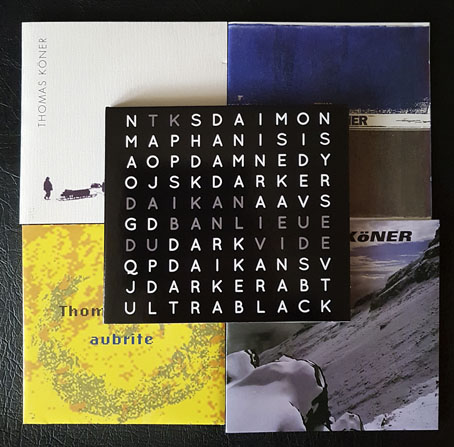

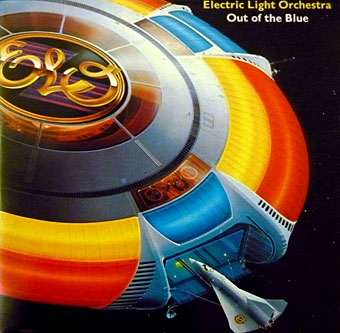

Out Of The Blue (1977) by Electric Light Orchestra.

Many different labels may be attached to the 1970s but it was definitely the science-fiction decade as much as anything else, a time when the use of SF imagery became a widespread trend, often superficially applied but there all the same. You see this in the music packaging of the period, and not only in the obvious enclaves of progressive rock. Here’s Motown Chartbusters Vol. 6 (1971) with a spaceship cover by Roger Dean; here’s Herbie Hancock on the cover of Thrust (1974) piloting his keyboard-driven craft over Machu Picchu while an alarmingly swollen Moon seems ready to crash into the Earth.

Out Of The Blue gatefold interior.

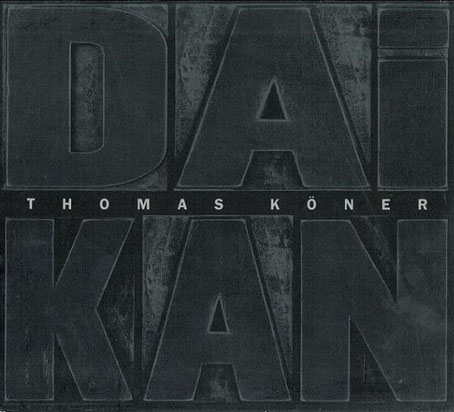

The exploitation of SF imagery on the covers of funk, soul and disco albums was much more widespread than the jazz world, and lasted long enough to join up with the emergence of synth-pop and electro in the early 1980s. The meticulous airbrush paintings of Shusei Nagaoka dominate this era and idiom, thanks in part to his covers for two of the biggest albums of 1977: Out Of The Blue by Electric Light Orchestra, and All ’n All by Earth, Wind & Fire.

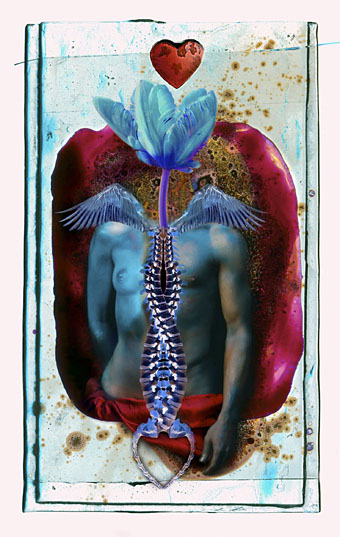

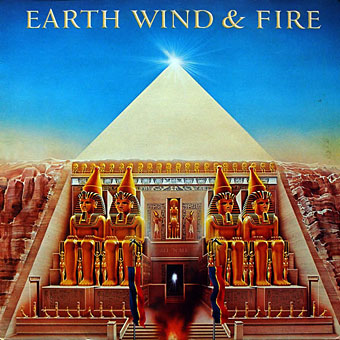

All ’n All (1977) by Earth, Wind & Fire.

The latter doesn’t look especially science-fictional until you flip it over and its Egyptian scene morphs into a futuristic cityscape with a fleet of rockets heading for the stars. (That pyramidal building is based on one of Paolo Soleri’s hexahedron megastructures.) Many of the albums that followed this pair were jumping on the post-Star Wars/Close Encounters SF bandwagon but there were other reasons for funk and disco artists to embrace the Space Age, as Jon Savage has noted: “Disco’s stateless, relentlessly technological focus lent itself to space/alien fantasies which are a very good way for minorities to express and deflect alienation: if you’re weird, it’s because you’re from another world. And this world cannot touch you.”

Munich Machine (1977) by Munich Machine. (A Giorgio Moroder production.)

Nagaoka was in demand for his cover art even before hitching a ride to the top of the album charts so what you see here is a limited selection. As usual, there’s more to be seen at Discogs although I often wish they’d allow larger image uploads. Future Life magazine ran a feature about Nagaoka in October 1978 which includes a brief interview with the artist together with some biographical details.

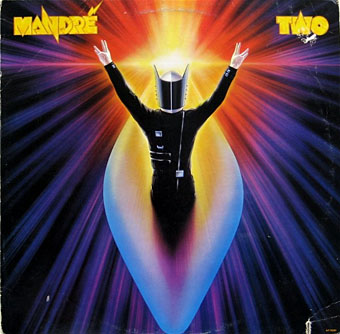

Mandré Two (1978) by Mandré.