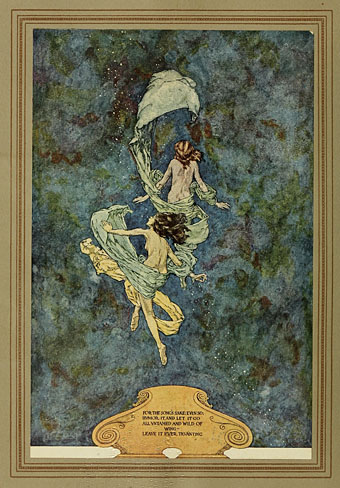

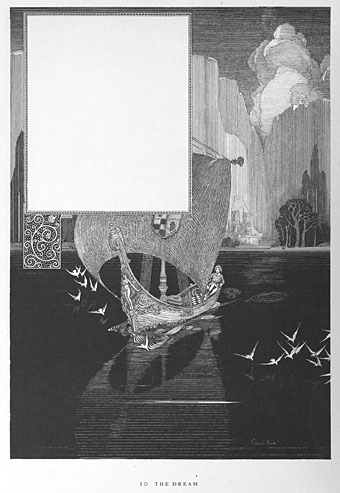

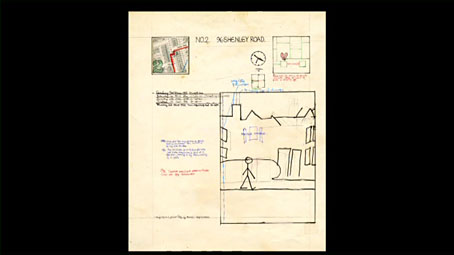

A page from the score for Makrokosmos I (1972) by George Crumb.

American composer George Crumb died in February at the age of 92, something I only discovered a couple of months ago. Outside the USA he always seemed like an obscure figure, seldom mentioned in British newspapers (although The Guardian did run an obituary), with even a sympathetic magazine like The Wire only interviewing him once in February 1997. Well, I have a perverse attraction to the art made by overlooked mavericks, and I’d managed to accumulate several recordings of Crumb’s compositions after being alerted to his existence by Jack Sullivan’s profile in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural (1986), a book that Sullivan also edited which turned out to be a surprisingly useful music guide. Sullivan’s entries were invaluable at the time for discussing classical music and composers from an uncommon point of view, namely the degree to which various compositions might be considered a part of the horror genre, whatever the original intention behind their writing. Musicologists would dismiss such an approach as vulgar but I was pleased to read descriptions that for once used emotional words like “atmospheric”, “spectral”, “haunting”, or “chilling”, instead of the formal analysis of timbres and tone clusters that you find in sleeve notes; Sullivan even describes one of Crumb’s orchestral works as “a terrifying racket” which is exactly the kind of thing I like to be told if I’m going to spend time tracking down scarce recordings.

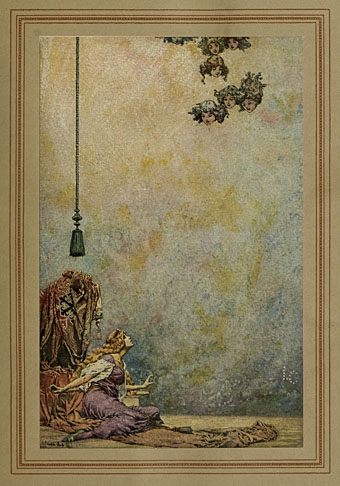

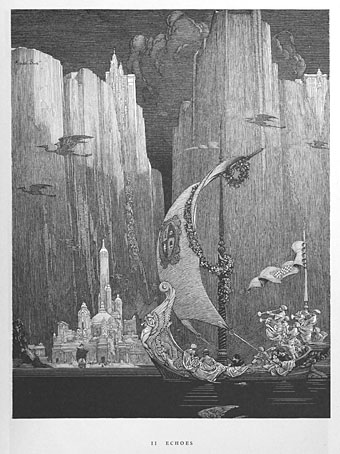

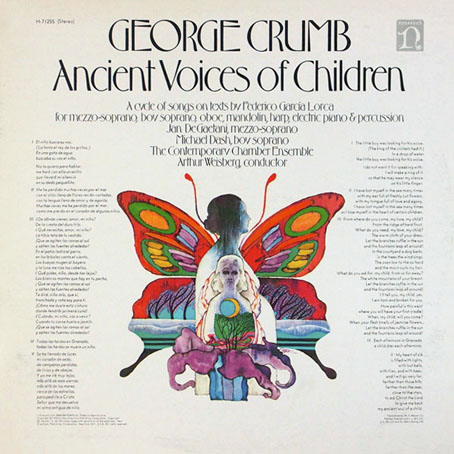

Cover art by Bob Pepper, 1971.

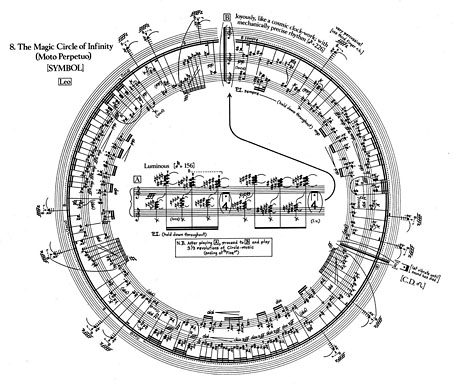

Not everything by Crumb belongs in a horror encyclopedia but his most celebrated composition, Black Angels: Thirteen Images from the Dark Land (1970), certainly does, a string quartet for amplified instruments augmented by glass and metal percussion. The opening section, Threnody I: Night of the Electric Insects, is shriekingly violent, a response to the use of attack helicopters in Vietnam that also shows Crumb’s predilection for an evocative title. His Makrokosmos suites for amplified piano include sections with titles like The Phantom Gondolier, Music of Shadows, and Ghost-Nocturne: for the Druids of Stonehenge, while later compositions include Apparition (1979) and A Haunted Landscape (1984). The four volumes of Makrokosmos belong in Sullivan’s “spectral” category, with the performer(s) being required to sporadically shout, whistle and strum the strings of the piano. Unusual sounds and unorthodox approaches to instrumentation and performance were a consistent feature of Crumb’s compositions.

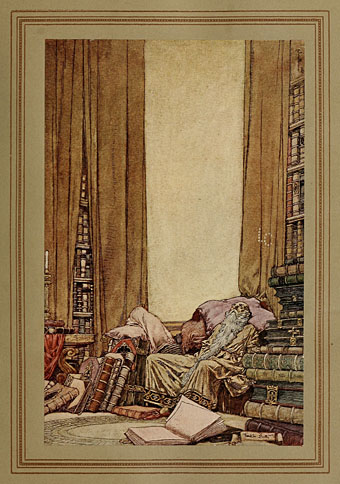

Cover design by Paula Bisacca, 1975.

For the curious or uninitiated, George Crumb – His Life and Work is a 28-minute compilation of pre-existing video pieces put together by Andreas Xenopoulos that provides a useful introduction to the composer. Extracts from an interview with Crumb are interleaved with examples of his music that include a few glimpses of live performance. I’m very familiar with the first three volumes of Makrokosmos but these extracts made me realise that I’d never seen them performed before, so I’d never considered the amount of times the pianists have to manipulate the piano strings while they’re playing the keys. Black Angels requires similar input from the performers—whispering, shouting, bowing tam tams and tuned wine glasses—something referred to by David Harrington of the Kronos Quartet in another interview extract. Black Angels is a particularly important part of the Kronos Quartet’s repertoire (I recommend their 1990 recording), being the composition that prompted Harrington to form the quartet in the first place. YouTube has a number of live performances including this one by Ensemble Intercontemporain. Play loud.

For a composer with a career spanning several decades, Xenopoulos’s compilation might have been longer but most of the extracts still seem to be present in full elsewhere. And while I usually dislike Christmas music, given the time of year I’ll direct your attention to Crumb’s A Little Suite For Christmas, AD 1979 played by Ricardo Descalzo. The piece wouldn’t have warranted a mention in the horror encyclopedia but it isn’t tinselly nonsense either.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• A playlist for Halloween: Orchestral and electro-acoustic