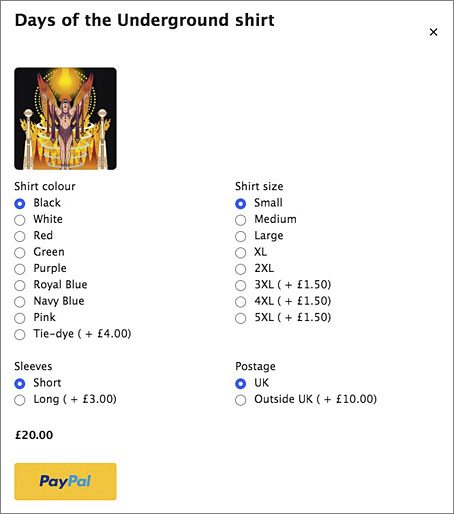

Another advantage of the recent WordPress upgrade means I can now do things like this. The photo is a Prague street scene that I found in a newspaper years ago which I decided to depopulate in Photoshop. In the past you could only do this with a special plugin but WordPress changed the user interface a while back from a basic write-text-and-add-media arrangement to a more complex editing system known as Gutenberg. The new editor uses CSS-style blocks which you fill with different types of “content” then shuffle around until you have a layout that you’re happy with. You can do a lot with these blocks but most of the tools that control them are hidden from view behind multiple menus and sub-menus; using the system means you first have to learn and memorise the location and function of all these hidden tools. Users of standalone installations of WordPress are a loyal bunch but there was a very negative reaction to the new editor, so much so that a plugin appeared almost immediately which reverts the interface to the former system. WordPress continues to evolve Gutenberg, however, and now provides a variety of media blocks like this picture-comparison thing. The utility is limited but it looks nice.

I’m in the anti-Gutenberg camp for the most part, especially when looking at the code that makes something like this possible. Most of the posts here are written outside WP as plain text with handwritten HTML tags; Gutenberg adds loads of new tags and instructions that clutter up the back end. I may work as a book designer but a print-style layout isn’t what I want to emulate for these pages. (And the Adobe applications I use don’t hide all their controls unless you really want them to.) Gutenberg is no doubt useful for people with big media websites using WordPress as a CMS to create layouts filled with articles, video and the like. But I’ll be sticking with the old system for now.