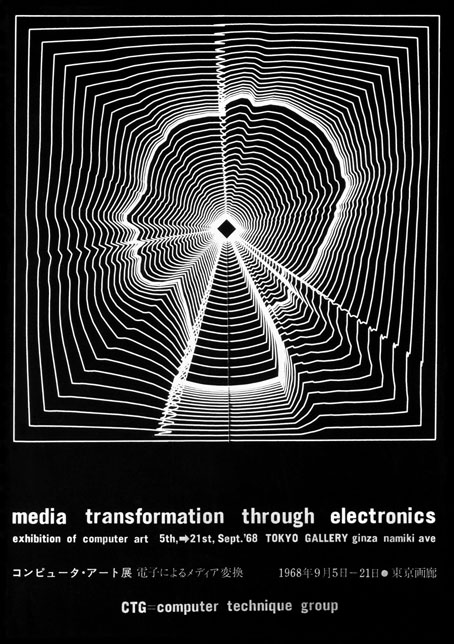

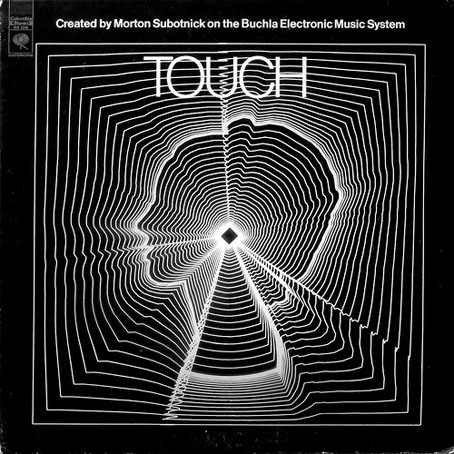

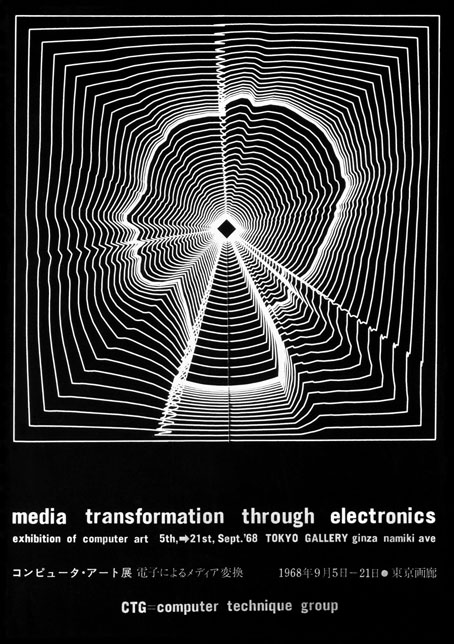

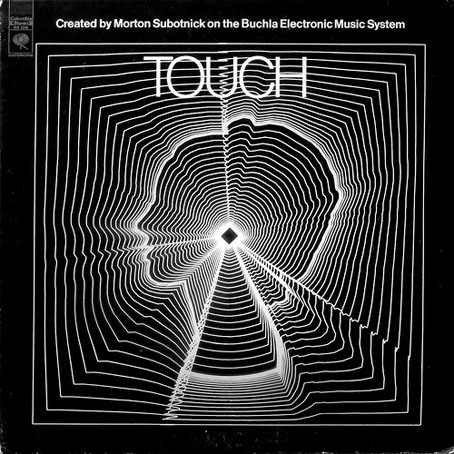

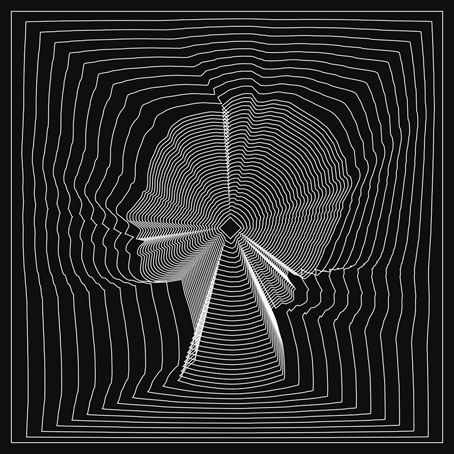

“Media transformation through electronics” might be a description of the internet but the phrase here is the title of an exhibition of Japanese computer art by CTG, the Computer Technique Group, which took place in Tokyo in 1968. The image on the poster is Return to Square, an example of incremental transformation conceived by Masao Komura and programmed by Kunio Yamanaka which is the most well-known work produced by the group. Morton Subotnick used Yamanaka’s print a year later on the cover of his third album, Touch, which is where I first encountered it.

After reading this recent interview with Subotnick I was listening again to some of his albums, Touch included, which in turn prompted me to go looking for more information about the cover art. Following Yamanaka’s history back to the CTG revealed two versions of Return to Square. The image on the exhibition poster and the Subotnick cover is the second version, Return to Square (b) which in both cases is printed in negative, or reversed-out to use the technical term that printers prefer. This version takes 30 incremental steps from the shape of the woman’s head to reach the central square.

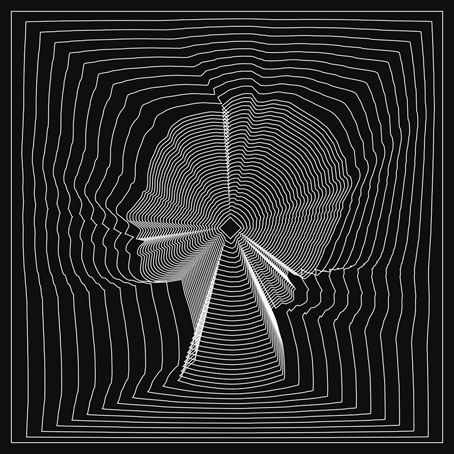

The first version, Return to Square (a), is more densely printed inside the head, taking 50 steps to reach the central square. According to a description in the Cybernetic Serendipity catalogue (see below), the difference between the versions is also a result of the programming: version (a) is programmed with an arithmetic series, while version (b) uses a geometric progression. Return to Square (a) achieved some prominence of its own when it was reproduced in 1967 by Motif Editions, a British publisher of lithographs who made prints from several images derived from experiments with computer graphics. I can’t say where Subotnick first saw Yamanaka’s print but it’s a great choice for the cover of an album of avant-garde electronic music. You’ll only see it today, however, on old vinyl copies (or on 8-track cassettes) since Touch hasn’t been reissued as a standalone album since 1972. The whole composition runs for 30 minutes which means on CD (or audio-DVD, as with one of my discs) you only find it bundled with other Subotnick compositions.

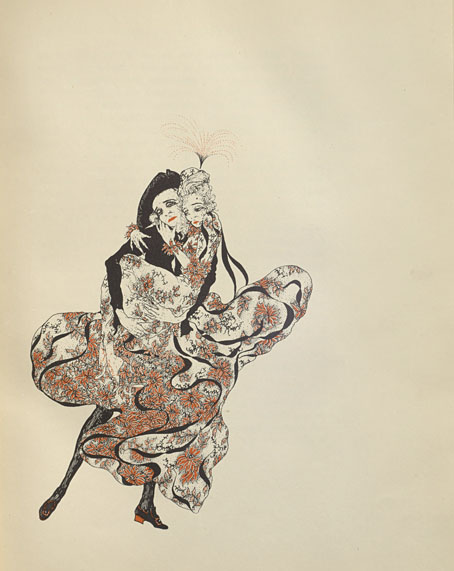

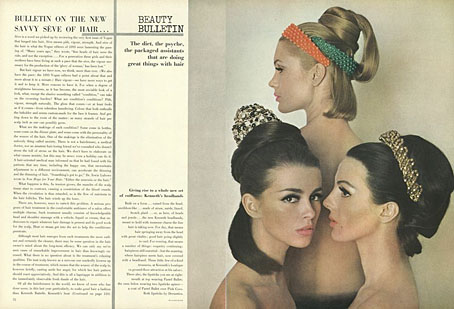

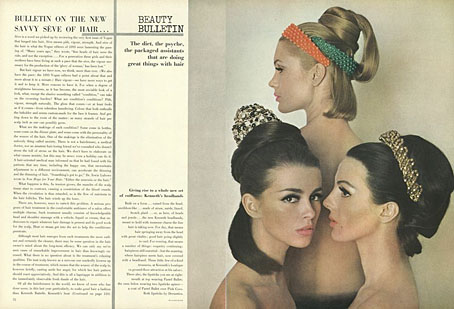

Photo by William Klein.

While tracing the history of Yamanaka’s print I didn’t expect to find the source for the outline of the woman’s head but here it is, a spread from a 1964 issue of Vogue magazine. This detail comes from a short post by Zihou Ng which not only gives you the code that Yamanaka used to create Return to Square (a) but also has a small interactive rendering of the image which you can push around and distort: “media transformation through electronics”.

Less successful than Ng’s recreation is this attempt by myself to make a version of Return to Square (b) in Illustrator. I use Adobe’s vector-graphics application almost as much as I use Photoshop but some of the standard Illustrator tools I find to be of limited utility. The shape-blending tool is one of these but it’s what I used to make this recreation. The lack of accuracy is a result of its limited settings: you define the number of steps you want it to take then click on two shapes in succession and the tool fills the space between them with iterative transformations. Rather a blunt instrument but this took me all of 15 minutes to create, a fraction of the time that Yamanaka would have spent programming his original.

• Related reading: Cybernetic Serendipity, PDFs (high- and low-res) of a catalogue for an exhibition of computer art at the ICA, London, in 1968. Includes a profile of the Computer Technique Group with examples of their work. The low-res scan has a few extra pages at the end which include an ad for Motif Editions.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Gioconda of the Mausoleum

• Golden apples and silver apples