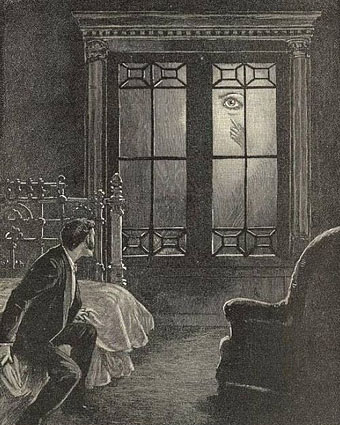

Illustration by Alfred Pearse for The Horror of Studley Grange by Clifford Halifax & LT Meade. Via.

• The Haunting at 60: Guy Lodge asks “Is it still one of the scariest films ever made?” I say yes but then it’s always been a favourite. Also, Robert Wise is something of a cult figure in this house, not for his big-budget directing jobs on The Sound of Music and Star Trek: The Motion Picture, but for his RKO horror entries (The Curse of the Cat People and The Body Snatcher), his film noir (Born To Kill, The Set-Up, Odds Against Tomorrow), and two smaller science-fiction films from different decades, The Day the Earth Stood Still and The Andromeda Strain. All this and he also edited Citizen Kane.

• “This show makes an irrefutable case for her technical mastery while also affirming her as a first-rate fabulist whose disparate influences—chivalric romance, medieval architecture, tarot, psychology, astronomy, and much more—cohere into a visionary whole.” Jeremy Lybarger reviewing Science Fictions, the retrospective devoted to the art of Remedios Varo.

• New music: Improvisation On Four Sequences by Suzanne Ciani; Incorporeal by Hidden Horse; Atlas by Laurel Halo; Infinito (Version) by Moritz von Oswald.

While Ballard’s more outwardly conventional books may give us solider, more stable realities, what these realities often present…is a child (or childlike figure) frolicking against a backdrop provided by the destruction of an older order of reality that the world previously took for granted. It’s a cipher for his oeuvre as a whole: endlessly playing among the ruins, reassembling the broken or “found” pieces (styles, genres, codes, histories) with a passion rendered all the more intense and focused by the knowledge that it’s all—culture, the social order, the beliefs that underpin civilization—constructed, and can just as easily be unconstructed, reverse engineered back down to the barbaric shards from which it was cobbled together in the first place. To put it in Dorothean: In every context and at every level, Ballard’s gaze is fixed, fixated, on the man behind the curtain, not the wizard.

Tom McCarthy: JG Ballard’s Brilliant, Not “Good” Writing

• At Public Domain Review: Behold the Nebulous Smear: ‘Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi’s Illustrated Book of Fixed Stars (ca. 1430).

• At Unquiet Things: Shake, Shiver, and Shriek: The Haunted Gothic Nightmares of George Ziel.

• Winners of Nature TTL Photographer of the Year 2023.

• The Strange World of…Gavin Bryars

• Watch The Stars (1968) by Pentangle | Stars (1983) by Brian Eno with Daniel Lanois & Roger Eno | Kelly Watch The Stars (1997) by Air