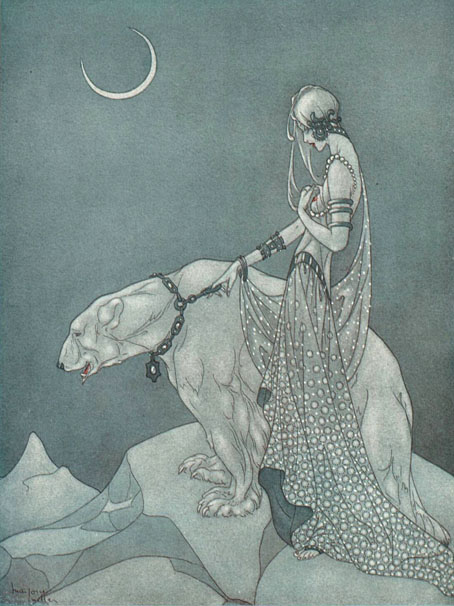

The Great Bear (1933) by Marjorie Miller.

• New music: “Lo-fi no-fi post-fi fragments of disparate SCATTERBRAIN thoughts scrapbooked together using industrial glue discretely purloined from building site tea-break opportunities to fully form the definitive SEPIA PUNK AMBIENT (?) statement of assiduous apathy intent ~ hextracted from SEPIA CAT CITY (GEpH017LP) available via moonwiringclub.com areet now TA.” Nobody writes product descriptions like Moon Wiring Club.

• “Both the Harry Smith and the Sun Ra books were hard sells, because they were virtual unknowns who had pretty much given their life for art. In each case only about two publishers were interested in either one of them. The editors said either that they hadn’t heard of him, or else they had heard of him and didn’t want to hear any more.” John Szwed talking to Raymond Foye about the mercurial Harry Smith, and the problems of writing biography.

• At Public Domain Review: Max Beerbohm’s A Christmas Garland (1912), a collection of seasonal parodies of well-known writers of the day. As with any such work, the success of each piece depends upon familiarity with the author being parodied, but Beerbohm’s prose is always a delight.

• Mirrorshades (1986), the cyberpunk story anthology edited by Bruce Sterling, is currently available for reading or e-text download at Rudy Rucker’s website. The book is still in copyright but I’m guessing this has been done with the agreement of the contributors.

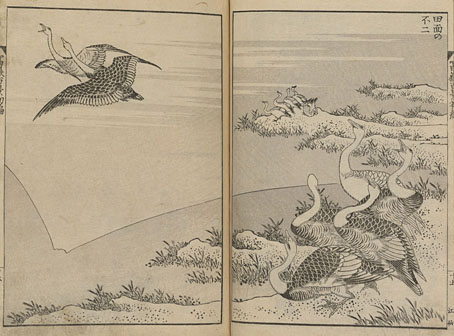

• “…the richness of terrestrial creatures which at points are capable of sounding utterly extra-terrestrial.” Daryl Worthington explores the history of birdsong and its influence on human music.

• At Smithsonian Magazine: Listen to the centre of the Milky Way translated into sound or look at yet more photos of the aurora borealis. (Or do both at the same time.)

• At Wormwoodiana: Through the Golden Valley to the Dark Tower. Mark Valentine and friends go on a book-buying expedition.

• 14 x 14, a collection of Oulipo poems by Ian Monk, translated by Monk and Philip Terry, with collage cover art by Allan Kausch.

• “I am fascinated by electromagnetic waves.” Carsten Nicolai (aka Alva Noto) discussing art and creativity with Max Dax.

• Secret Satan, 2023, the essential end-of-year book list from Strange Flowers.

• Spice Islands Sea Birds (1957) by Les Baxter | Trippin’ With The Birds (1997) by Stereolab + Nurse With Wound | Strange Birds (1999) by Coil