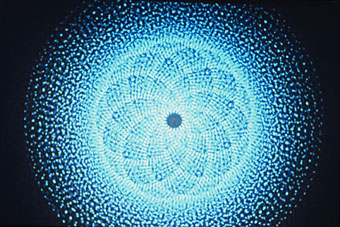

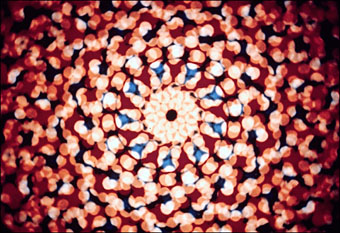

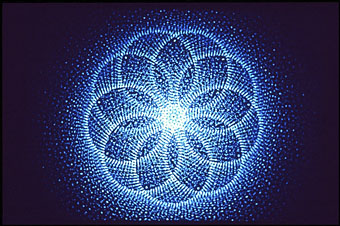

After complaining a couple of days ago about the difficulty of seeing works of abstract cinema, it turns out that a collection of Oskar Fischinger’s great animations appeared earlier this year.

Decades before computer graphics, before music videos, even before Fantasia (the 1940 version), there were the abstract animated films of Oskar Fischinger (1900–1967), master of “absolute” or nonobjective filmmaking. He was cinema’s Kandinsky, an animator who, beginning in the 1920’s in Germany, created exquisite “visual music” using geometric patterns and shapes choreographed tightly to classical music and jazz. (John Canemaker, New York Times)

Oskar Fischinger is one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, embracing the abstraction that became the major art movement of that century, and exploring the new technology of the cinema to open abstract painting into a new Visual Music that performs in liquid time. (Biographer William Moritz)

We now understand Oskar Fischinger not only as a link between the geometric painting of pre-war Europe and post-war California but as a grandfather of the digital arts.

(Art Critic Peter Frank)

That’s good, so now how about the Whitneys, Jordan Belson, Harry Smith…?

Via Boing Boing.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The abstract cinema archive