At the weekend I finally caught up with Peter Strickland’s latest, Flux Gourmet. These films (and their soundtracks): I recommend them.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Peter Strickland’s Stone Tape

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

At the weekend I finally caught up with Peter Strickland’s latest, Flux Gourmet. These films (and their soundtracks): I recommend them.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Peter Strickland’s Stone Tape

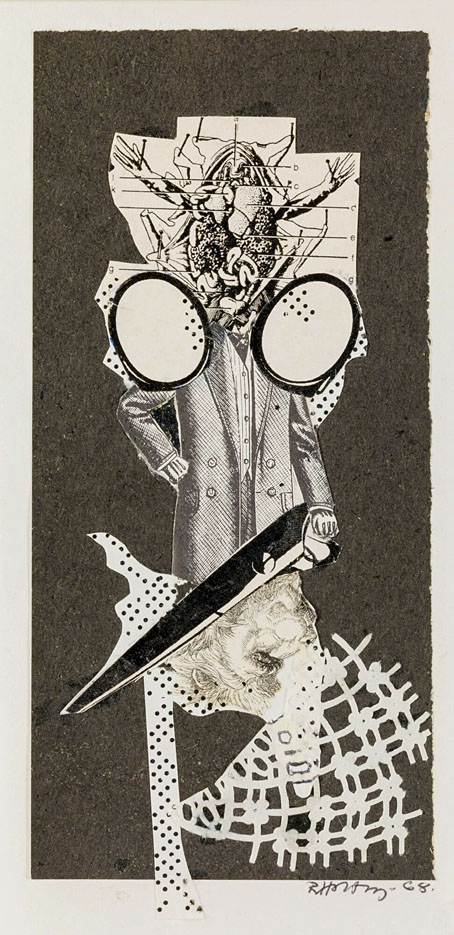

More Maldoror, and more collage, this time from Swedish artist and art historian Ragnar von Holten (1934–2009). The Historical Dictionary of Surrealism describes von Holten as a Gustave Moreau enthusiast who first contacted the Paris Surrealists in 1960 when he was organising a retrospective of Moreau’s work at the Louvre. André Breton had long been a champion of Moreau, especially in the decades when the artist was out of fashion, and wrote a preface for von Holten’s L’Art Fantastique Gustave Moreau. One of the many things I like about the Surrealists is the continuity they provide with the history of fantastic and visionary art.

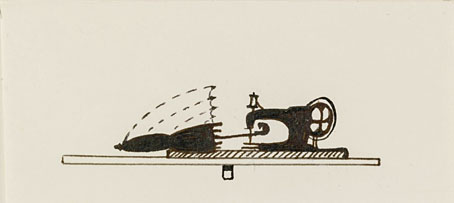

Von Holten’s Maldoror collages were begun in the late 1960s and completed in 1972 when they were published in a Swedish edition of the novel. I don’t know how many illustrations there were in all but you can see more at the Moderna Museet website. Not all the collages are labelled as being derived from Maldoror but many of the titles refer to the text all the same. Also there are two drawings intended as vignettes, one of which depicts in a rather literal fashion Lautréamont’s most popular metaphor.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

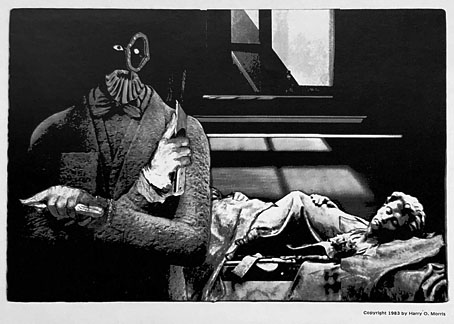

• Harry O. Morris’s Maldoror

• Covering Maldoror

• Kenneth Anger’s Maldoror

• Chance encounters on the dissecting table

• Santiago Caruso’s Maldoror

• Jacques Houplain’s Maldoror

• Hans Bellmer’s Maldoror

• Les Chants de Maldoror by Shuji Terayama

• Polypodes

• Ulysses versus Maldoror

• Maldoror

• Books of blood

• Magritte’s Maldoror

• Frans De Geetere’s illustrated Maldoror

• Maldoror illustrated

Landscape from a Dream (1936–38) by Paul Nash.

• “I was telling a close friend recently, ‘at my funeral, please play this record…’” Yu Su on her love of Laurie Anderson’s second album, Mister Heartbreak.

• “Surrealism is more of an attitude than an art movement,” says Mark Polizzotti, talking about his new book, Why Surrealism Matters.

• New music: Spinning by Julia Holter; The Night Dwells In The Day by Jozef Van Wissem; and The River Of Light And Radiation by Ben Frost.

• The late David J. Skal, author of Hollywood Gothic and others, is remembered at Swan River Press.

• At Colossal: Dizzying gifs by Etienne Jacob infuse mathematical equations into endless loops.

• At Public Domain Review: Charles Rabot’s Arctic photographs (ca. 1881).

• At Unquiet Things, S. Elizabeth says “Help me downsize my library!”

• Drone footage of the recent volcanic eruption in Iceland.

• Mix of the week is a mix for The Wire by Kavari.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Robert Bresson Day.

• Dance On A Volcano (1975) by Genesis | Volcano Diving (1989) by David Van Tieghem | Eye Of The Volcano (2006) by Stereolab

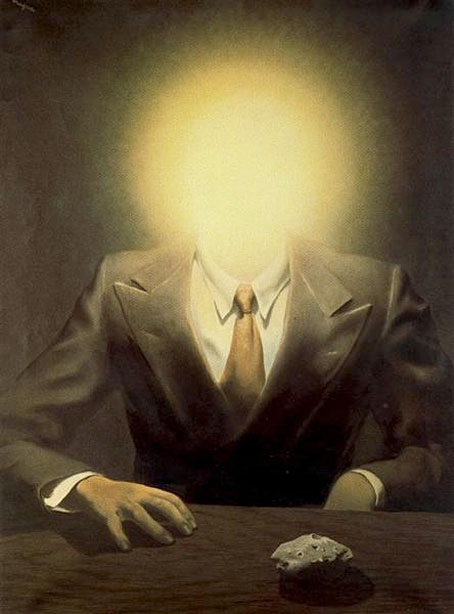

The Pleasure Principle (Portrait of Edward James) (1937) by René Magritte.

I was reading a book about Surrealism recently that I won’t shame by naming even though it was a bad piece of work: rambling, repetitive and with one section padded out by unfounded speculation. I managed to get a third of the way through before losing my patience when the author began to refer repeatedly to the wealthy British art patron “Edward Jones”. Edward James, as he’s more usually known, is a name guaranteed to turn up eventually in histories of 20th-century Surrealist art; despite not considering himself a collector James managed to amass the largest personal accumulation of Surrealist art in the world. For several years he was a patron of many artists including Dalí, Magritte and Leonora Carrington, becoming a life-long friend of the latter when they both moved to Mexico. He was also the model for some of Magritte’s paintings, including the very influential Reproduction Forbidden. The book that misnamed him was from a major British publisher, one who I usually regard as reliable which makes an error such as this especially annoying.

Anyway…much of the history of Edward James’s involvement with the Surrealists is recounted in this hour-long documentary made in 1995 by Avery Danziger and Sarah Stein, a run through James’s charmed life, from gilded youth as an aristocrat and inheritor of vast wealth, to his old age as “Uncle Edward”, a benevolent eccentric living in the Mexican jungle at Xilitla where he spent many years constructing his own work of art, the concrete fantasia known as Las Pozas. Substantial portions of the documentary are lifted from Patrick Boyle’s The Secret Life of Edward James, a TV profile made in 1978 that caught the man at a time when Surrealism in Britain was briefly trendy again thanks to a large retrospective exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in London. Danziger and Stein’s film is a kind of supplement to Boyle’s, showing us a more complete Las Pozas while fleshing out the impressions of James via new interviews with his friends and colleagues. Not everyone who gets thanked at the end made the final cut, so there’s no Leonor Fini unfortunately, but Leonora Carrington is present via shots from the Boyle film and extracts from a taped interview.

One aspect of Las Pozas that seldom gets mentioned (although I think George Melly might have made the connection) is the degree to which the place fits into the tradition of folly-building by wealthy British aristocrats. Follies are a familiar architectural feature of Britain’s stately homes, and being architectural caprices they come in all shapes and sizes. Most tend to be small one-off constructions, often taking the form of towers or fake ruins. The only folly comparable in scale to Las Pozas is Portmeirion, the pastiche Mediterranean town built by Clough Williams-Ellis on the coast of north Wales. Williams-Ellis, like James, spent decades tinkering with his pet project, and both locations have ended up supporting themselves by offering hotel facilities to tourists. Portmeirion, however, lacks the strangeness of the cement anomalies at Las Pozas; the only thing that’s strange about the place is its departure from vernacular Welsh architecture. Imitation and trompe-l’oeil are common elements among British follies. The closest that Portmeirion came to Surrealism was in the 1960s when it was used as a location for The Prisoner TV series. I imagine James would have found Williams-Ellis’s architectural taste rather too neat and refined. Las Pozas is a wild place that must require continual attention to prevent it from being consumed by the surrounding jungle. One of the houses there is named after Max Ernst (Danziger and Stein interview the owner), and it’s the fantasy jungles in the paintings of Ernst and Henri Rousseau that Las Pozas takes as its model.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Eco del Universo

• The Secret Life of Edward James

• Palais Idéal panoramas

• Las Pozas panoramas

• Return to Las Pozas

• Las Pozas and Edward James

Lautréamont’s delirious prose poem/novel/proto-Surrealist dream-text is sufficiently wild and free-ranging to inspire many visual interpretations. One of the peculiarities of the book is that all these interpretations are valid to some degree, although some still suit the general tone better than others. Quite a few of the well-known Surrealist artists had a crack at illustrating Les Chants de Maldoror but artists who don’t illustrate on a regular basis have a tendency to gesture vaguely at the given text while offering yet more of their own concerns.

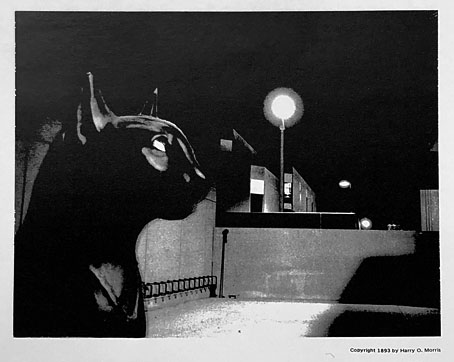

Expert collage artist Harry O. Morris does a better job than Dalí, Magritte and co. in his depictions of Lautréamont’s mutable scenarios. Maldoror is very much a collaged text, a product of its author’s enthusiastic plagiarism, which suggests that if the book has to be illustrated at all then collage is the technique to use. Morris’s interpretation was published in 1983 as Scenes from Lautréamont’s Maldoror, a portfolio of 10 plates. A note from the artist on this page acknowledges the influence of photo-montagist JK Potter, Morris being better known for his collages of engraved illustrations and other pictorial matter.