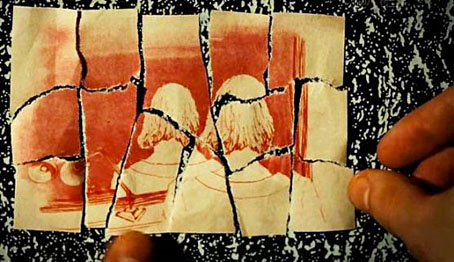

An assemblage by Steven Cline.

Joanna Moorhead writing in Surreal Spaces: The Life and Art of Leonora Carrington (Thames & Hudson, 2023):

Penelope [Rosemont] also remembers that Leonora was keen on what the group called their “Surrealist Survival Kits”; these were “a collection of poetic, magical, talismanic objects, along with images and other ‘Surrealist things’. A kit might include a feather, a pebble, a piece of glass, some verses from a poem. ‘The purpose of these kits is to offset the destructive facts of daily life, to pull us through the hardest times, to reawaken our sense of wonder and to renew our capacity for reverie and revolt.’” For Penelope, it spoke to Leonora’s wider vision of the world: “tentative, playful, humorous, generous, adventurous, egalitarian, non-dogmatic, the opposite of conventional either/or thinking”.

Penelope Rosemont writing in Surrealism: Inside the Magnetic Fields (City Lights, 2019):

Well, Leonora laughed and said, “Yes, I did that too. But what we really need now is a Surrealist Survival Kit,” and we had much fun deciding what would go into our Surrealist Survival Kit.

She spoke frequently of the urgent need for this special piece of equipment, the “Surrealist Survival Kit”—which is described by Kenneth Cox in the wonderful book What Will Be (2014) as a “collection of poetic, magical, talismanic objects, images, and other ‘favourite things.’ A kit could include, for example: a pebble, a feather, a bird’s egg, a piece of wood, a chunk of coral, a bead, a shell, a bit of coloured glass, a painting the size of a postage-stamp, a poem by Benjamin Péret, a ‘Let There Be Wolves!’ sticker). Every item small enough to keep in a cloth sack children kept marbles in.

“Its purpose: to offset the destructive effects of daily life, to pull us through the hardest times, to reawaken our sense of wonder and to renew our capacity for dream and action. Designed to function symbolically; each would be different, for no two people are exactly alike.

“Overcome by demoralization and defeat, depressed or suicidal, then is the time to open one’s “Surrealist Survival Kit” and enjoy a breath of magical fresh air. To lay out its marvellous contents carefully before oneself, one by one, and let the objects and images play together, arrange them, rearrange them, enter the play with them. Relaxing and soothing as well as exhilarating and reinvigorating. In other words, just what every surrealist needs.”

From Athens meeting report, June 2011, by SLAG (Surrealist London Action Group):

As we reflected together on the unfolding results of our game, we understood that what made the kits significant was not the personal collection of “favourite things” by individuals—“each one […] different, for no two people are exactly alike” in Penelope Rosemont’s words—but the process of assembling them, of finding or constructing oneiric objects from literally any old rubbish that was lying around, the transmutation of base matter into the gold of future time. In other words, our Survival Kit was not the objects themselves, but the ability to find and transform them. Surrealism is our survival kit, and as such is a necessary—though insufficient—condition for the social revolution that must come.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Leonora Carrington and the House of Fear