Patrick McGoohan.

Network DVD had a sale recently so I finally capitulated and bought the blu-ray set of The Prisoner which I finished watching this weekend. The picture quality is so outstanding it might have been made yesterday, and many of the extras are also essential for Prisoner obsessives, not least a restored print of the original cut of the first episode, something that was believed lost for years.

Episode 9: Checkmate.

There’s no need to enthuse about the series when I’ve done so already; this time round I’ll note that while the Cold War background is thoroughly outmoded some of the themes of particular episodes seem more relevant than ever. The model of total surveillance seen in the Village has for some time seemed to be one that Western governments and tech corporations would love to emulate. (“The whole world as the Village?” asks The Prisoner. “That’s my hope,” says Number 2.) The Prisoner isn’t the only drama to deal with authoritarian control, of course, but it also deals with the soft tyranny of closed communities, ideology and group-think. Episode 12, A Change of Mind, concerns a process whereby disobedient Villagers are confronted by their peers, declared “unmutual” then bundled off for corrective therapy; when they return they repent their antisocial crimes in public. In 1967 such a scenario would have seemed reminiscent either of McCarthyite America, or Soviet Russia and Maoist China; in 2015 you can be declared “unmutual” for minor infractions every day on the internet, and find yourself rounded upon by a sanctimonious horde.

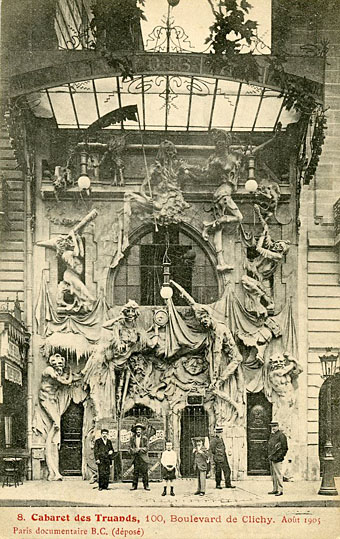

The allegorical and symbolic qualities of The Prisoner have kept the series fresh for almost 50 years while the character who launched the genre that gave rise to series—James Bond—has required several overhauls in order to keep up with changing times. Bond may bicker with his superiors but he’s always been a tool of the status quo, an agent of the Control virus in Burroughsian terms. In episode 8, The Dance of the Dead, The Prisoner is lectured by a judge in a kangaroo court on the importance of “the rules”. “Without rules, we have anarchy,” she says. The Prisoner, who happens to be dressed in a Bondian dinner jacket, replies “Hear, hear.”

Continue reading “Six Into One: The Prisoner File”