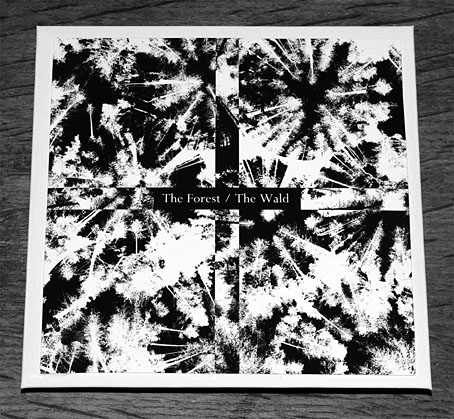

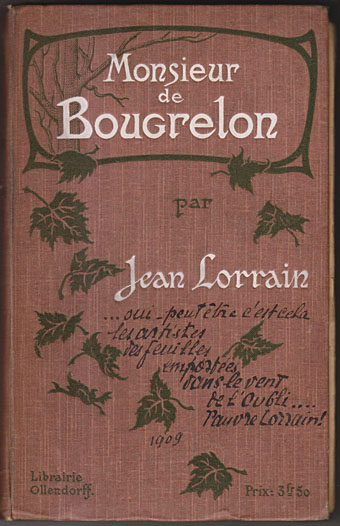

A reprint edition from 1909.

In 1881 there arrived from Normandy a good-looking young man with an unfortunate habit of painting his face: Jean Lorrain. He spent five years of his life in Montmartre, five years that were also the most dazzling ones for the hill whose chronicler he became. A brilliant journalist with an eye that missed no blemish, no absurdity, but could fill with tears on seeing beauty in a picture, a profile, a gown. From his first poems, Modernités, this fin-de-siècle Petronius evoked the whole life of Montmartre: transvestites, lesbians, go-betweens, outrageous bluestockings, failed poets declining into pimps, wrestlers, part-time gigolos for either sex.

Philippe Jullian in Montmartre (1977)

Among the books that Philippe Jullian wrote about notable fin-de-siècle personalities is a biography of Jean Lorrain (1855–1906), a volume which—to my continual frustration—has yet to be translated into English. If Lorrain is a neglected figure in contemporary France, he’s hardly known at all in the Anglophone world which is why the news last month of the first English translation of Monsieur de Bougrelon was so welcome.

Jean Lorrain (1898) by Antonio de la Gandara.

I say that Lorrain is unknown but only to the general reader; to anyone familiar with fin-de-siècle Paris he’s an unavoidable presence, a chronicler of the city’s excesses and also one of the great characters of the period. Portraits and cartoons show the dandy but fail to communicate the reek of ether—he was an addict throughout his later years—which attended his presence. His drug-taking helped contribute to an early death at the age of 55 but, like Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Lorrain managed to combine several years of indulgent pleasure-seeking with serious industry, producing over 40 literary works. Like Fassbinder he was also open about his homosexuality. The Paris of the 1890s wasn’t exactly enthusiastic about this but the Code Napoléon had never made homosexual acts a crime which is one of many reasons that Paris (and France in general) was a haven for the beleaguered British. In his sexual proclivities, his dandyism, and his aesthetic connoisseurship Lorrain is a good contender for a French equivalent of Oscar Wilde, another of Philippe Jullian’s biographical subjects. Lorrain wrote novels, plays and poetry, while his columns of journalism combined gossip and satire with tips for the aesthetically minded. His taste in people was (again) Fassbinderesque:

I have a great fondness for hoodlums, fairground wrestlers, butcher-boys and assorted pimps, both ordinary and extraordinary, who, along with some absolutely exquisite women and some men of talent, such as yourself, are the only company that I keep in Paris.

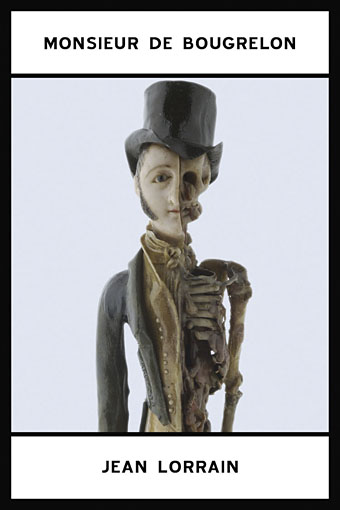

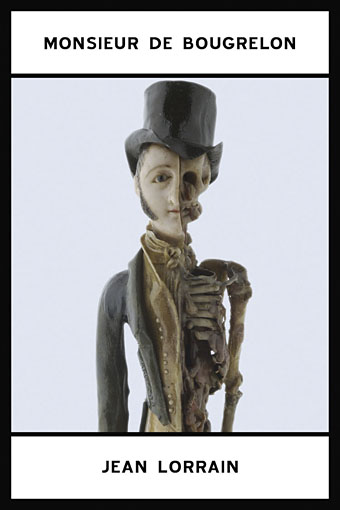

This life, and some of the author’s character, is reflected in Monsieur de Bougrelon, a short novel published in 1897. The story is narrated from the point of view of a pair of unnamed French visitors to Amsterdam who encounter their extraordinary compatriot when he makes a dramatic entrance into a cheap bordello. Monsieur de Bougrelon is an aged roué and purported aristocrat whose startling antique dress sense is dandyism gone to seed: swathed in old furs, bedizened with fake jewellery, and with dripping face-paint that prefigures another tragic figure in a city of canals, Thomas Mann’s Von Aschenbach. The French tourists have been made despondent by the dreariness of Amsterdam in winter so they welcome Monsieur de Bougrelon’s offer to lead them around the city, taking in museums, the city’s docks and the less reputable areas. While Monsieur de Bougrelon is present he maintains a running commentary, offering his opinions on the sights—Dutch art is amusingly dismissed as “bourgeois”—the people (“ugly”) and his own splendid life and lost loves. His tales about himself are tall and eventually verge on the improbable, but his presence engages the Parisians with its parade of lively invention, “imaginary pleasures” and phantom presences. Chief among the latter is Monsieur de Mortimer, de Bougrelon’s life-long friend, now dead and possibly the love of de Bougrelon’s life.

This last matter is explored in an afterword by Eva Richter, the translator. While Monsieur de Bougrelon claims to be interested in women he has always been devoted to Monsieur de Mortimer, and the pair survive various affairs and obsessions to remain in each other’s company. Lorrain alludes to the true nature of the relationship when de Bougrelon compares himself and de Mortimer to Achilles and Patroclus. The surnames also offer clues with Mortimer signalling death while Bougrelon is a combination of the French name Bouglon and the word “bougre” whose equivalent in English is “bugger”. The French may have been more accepting of certain behaviours than the British but there were still limits, and Lorrain’s dallying with obscenity and homosexuality is decades in advance of Proust, Gide and Genet. But this isn’t the full substance of the novel. Monsieur de Bougrelon may be short but it contains some marvellous flights of fancy and torrents of description; it’s also blackly humorous in parts, although the dominant tone is of melancholy and a nostalgic regret for vanished days and lives. Melancholy and the omnipresence of death is a common theme in Decadent literature; Lorrain alludes in passing to another short melancholy story set in a city of canals, George Rodenbach’s Bruges-la-Morte (1892).

Spurl Editions are to be commended for resurrecting this neglected novel which is diligently translated and annotated. Monsieur de Bougrelon will be published on November 1st when it will join Monsieur de Phocas and Nightmares of an Ether-Drinker (aka The Soul-Drinker and Other Decadent Fantasies) in being one of the few works available in English from an exotic bloom of the French fin de siècle.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• New Life for the Decadents by Philippe Jullian

• Philippe Jullian, connoisseur of the exotic

• Ma Petite Ville