Today’s post was convulsive in its beauty.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Topsychopor by Roland Topor

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Today’s post was convulsive in its beauty.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Topsychopor by Roland Topor

The Prague Ghetto, 1902, by A. Kaspara.

I looked away from him, and gazed instead at the discoloured buildings, standing there side by side in the rain like a herd of derelict, dripping animals. How uncanny and depraved they all seemed. Risen out of the ground, from the look of them, as fortuitously as so many weeds. Two of them were huddled up together against an old yellow stone wall, the last remaining vestige of an earlier building of considerable size. There they had stood for two centuries now, or it might be three, detached from the buildings around them; one of them slanting obliquely, with a roof like a retreating forehead; the one next to it jutting out like an eye-tooth.

Beneath this dreary sky they seemed to be standing in their sleep, without a trace revealed of that something hostile, something malicious, that at times seemed to permeate the very bricks of which they were composed, when the street was fllled with mists of autumn evenings that laid a veil upon their features.

In this age I now inhabit, a persistent feeling clings to me, as though at certain hours of the night and early morning grey these houses took mysterious counsel together, one with another. The walls would be subject to faint, inexplicable tremors; strange sounds would creep along the roofs and down the gutters—sounds that our human ears might register, maybe, but whose origin remained beyond our power to fathom, even had we cared to try.

(Translation by Mike Mitchell)

Watching Jiri Barta’s films again, and thinking about his unfinished adaptation of The Golem, prompted me to return to the source.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Stone Glory, a film by Jirí Lehovec

• The Face of Prague

• Josef Sudek

• Das Haus zur letzten Latern

• Hugo Steiner-Prag’s Golem

• Karel Plicka’s views of Prague

• Barta’s Golem

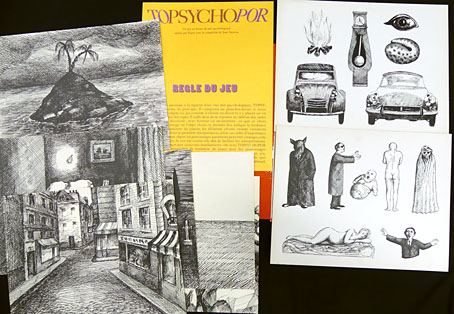

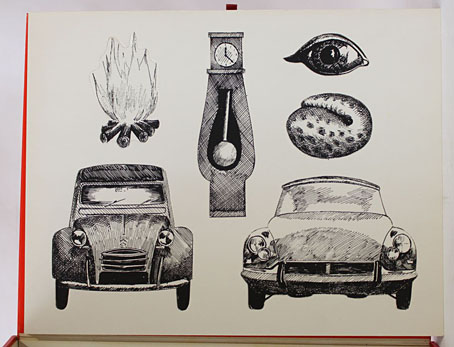

Published in Paris in 1964, “a game in the form of a psychological test produced by Topor with the help of Jean Suyeux”. A red box measuring 41 x 32 cm, containing 6 “decor boards” or stages which depict a street, a region of rocks, a cemetery, a bedroom, a plain and an island; plus two sheets of pre-cut characters: a fire, a clock, an eye, a shell, two Citroën autmobiles (a 2CV and a DS), a wolfman, a blind man, a baby, a naked man, Death, a sleeping woman, and a truncated man.

“Sans prétendre atteindre à la rigueur d’un vrai test psychologique, TOPSYCHOPOR en utilise les principes. Il comprend six planches-décors et treize personnages ou objets. Le jeu consiste à choisir un décor et à y placer un ou plusieurs éléments découpés. ll suffit alors de se reporter au tableau des interprétations pour découvrir—avec horreur ou ravissement—ce que ce choix signifie. Le personnage ou l’objet choisi en premier lieu indique la tendance dominante du caractère du joueur, les éléments choisis ensuite viendront nuancer et compléter la première interprétation, selon un ordre d’importance décroissant. Certains objets ou personnages paraîtront peut-êtrc étranges; cela ne doit pas étonner, ils ont été voulus tels afin de faciliter les interprétations. Vous verrez d’ailleurs que vous vous familiariserez vite avec TOPSYCHOPOR et bientôt vous ressentirez la tentation de jouer avec lcs personnages sans plus vous soucier de leur signification. Car ce jeu cache son jeu, un jeu auquel vous vous prendrez. Pour l’interprétation des récits que vous ferez alors, vous pourrez toujours consulter votre psychiatre habituel.”

Rules of the game (autotranslated): “Without claiming to achieve the rigor of a real psychological test, TOPSYCHOPOR uses its principles. It includes six decor boards and thirteen characters or objects. The game consists of choosing a decor and placing one or more cut elements in it. It is then enough to refer to the table of interpretations to discover—with horror or delight—what this choice means. The character or object chosen in the first place indicates the dominant tendency of the player’s character, the elements then chosen will come to qualify and complete the first interpretation, in order of decreasing importance. Some objects or characters may appear strange; that should not surprise, they were wanted such in order to facilitate the interpretations. You will see that you will quickly become familiar with TOPSYCHOPOR and soon you will feel the temptation to play with the characters without worrying about their meaning. Because this game hides its game, a game that you will take. For the interpretation of the stories that you will then make, you can always consult your usual psychiatrist.”

I don’t have a copy of this, unfortunately (and please don’t tell me you have one to sell). Picture searches kept turning up links to film festivals which was a little confusing until I realised that there’s a short film by Antonin Peretjatko, Mandico et le TOpsychoPOR, about a man encountering the game.

Random House offering readers a guide to the labyrinth in 1934.

I’ve not done a Bloomsday post for the past couple of years so here you go. Via Jorge Luis Borges: Selected Non-Fictions (1999), edited by Eliot Weinberger.

A total reality teems vociferously in the pages of Ulysses, and not the mediocre reality of those who notice in the world only the abstract operations of the mind and its ambitious fear of not being able to overcome death, nor that other reality that enters only our senses, juxtaposing our flesh and the streets, the moon and the well. The duality of existence dwells within this book, an ontological anxiety that is amazed not merely at being, but at being in this particular world where there are entranceways and words and playing cards and electric writing upon the translucence of the night. In no other book (except perhaps those written by Gómez de la Serna) do we witness the actual presence of things with such convincing firmness. All things are latent, and the diction of any voice is capable of making them emerge and of leading the reader down their avenue. De Quincey recounts that it was enough to name the Roman consul in his dreams to set off fiery visions of flying banners and military splendor. In the fifteenth chapter of his work, Joyce sketches a delirious brothel scene, and the chance conjuring of any loose phrase or idea ushers in hundreds—the sum is not an exaggeration but exact—of absurd speakers and impossible events.

(1925; translated by Suzanne Jill Levene.)

Plenitude and indigence coexist in Joyce. Lacking the capacity to construct (which his gods did not bestow on him, and which he was forced to make up for with arduous symmetries and labyrinths), he enjoyed a gift for words, a felicitous verbal omnipotence that can without exaggeration or imprecision be likened to Hamlet or the Urn Burial…Ulysses (as everyone knows) is the story of a single day, within the perimeter of a single city. In this voluntary limitation, it is legitimate to perceive something more than an Aristotelian elegance: it can legitimately be inferred that for Joyce every day was in some secret way the irreparable Day of Judgment; every place, Hell or Purgatory.

(1941; translated by Esther Allen.)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• A Portrait of the Author

• The Labyrinth

• The Duc de Joyeux

• Dubliners

• Covering Joyce

• James Joyce in Reverbstorm

• Joyce in Time

• Happy Bloomsday

• Passages from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

• Books for Bloomsday

A new purchase. It’s excessive and wasteful to order DVDs from South Korea but when this is the only available option you have no choice. Jiri Barta: Labyrinth of Darkness is a Korean clone of a deleted disc that was originally released in the US by Kino, and which I’d managed to miss when it was still easy to find. The collection gathers all of the Czech animator’s short films from 1978–89 plus his 53-minute masterwork, The Pied Piper (1986), a film whose Expressionist puppets and decor steal the familiar folk tale away from picture-book cuteness and return it to its darker roots. The subtitle “Labyrinth of Darkness” suggests that all the films tend towards horror which isn’t really the case, although anyone disturbed by animated shop mannequins may be unnerved by Club of the Discarded (1989). Barta’s films can be dark but they’re also wry or quirky: The Design (1981) is a wordless fable about the imposition of social uniformity by contemporary architecture, while The Extinct World of Gloves (1982) cleverly uses anthropomorphism to pastiche a range of cinematic genres. Barta is still active today but most of his recent films have been advertising commissions and a child-friendly feature, Toys in the Attic, the marketplace being resistant to animation that’s too strange or personal. I still hope we might one day see his feature-length film of The Golem but there’s been no news about this since a preview was released in 2002:

“Everyone is expecting a fairytale about that legend. Our interpretation is a little bit different, because we start from another point of view, which is Gustav Meyrink’s Golem…It is much more interesting, but I think that this is the reason why we have not moved forward, why the whole project has stopped, why some producers have disappeared, appeared and disappeared again.” (via)

The unavailability of the Kino disc of Barta’s films is part of a worrying trend for those of us who like to own physical copies of scarce films. Many DVDs released ten or more years ago are now deleted and—in the case of my precious Piotr Kamler collection—impossible to find, while the films they contain are of such minority interest there’s little hope of seeing them on blu-ray any time soon. In the hierarchy of cinematic value, feature-length dramas always receive the most attention while documentaries, shorts, animations and experimental films are subject to the greatest neglect. Yes, “everything is now on YouTube” (except when it isn’t), but invariably compromised by low resolution, a lack of subtitles, or blighted by TV watermarks. And everything on YouTube is only there for as long as the uploader maintains their channel or until someone files a copyright complaint; previous posts here are filled with links to videos that are now deleted, so the Koreans are doing everyone a service by keeping Barta’s films in circulation. The same goes for the great René Laloux whose science-fiction features, Time Masters (1982) and Gandahar (1987), are currently available with English subs only from South Korea. The quality of this Jiri Barta disc leaves much to be desired but it’s still better than YouTube.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Jiri Barta’s Pied Piper

• Gloves

• More Golems

• Barta’s Golem