In times of great uncertainty about our mission, we often looked at the fixed points of Lautréamont and De Chirico, which sufficed to determine our straight line.

André Breton, Surrealism and Painting, 1928

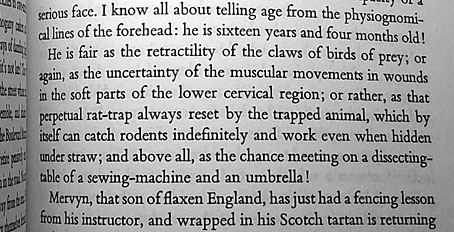

1: The metaphor, 1869

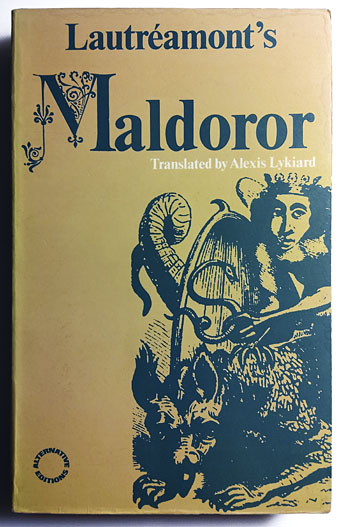

You can’t read the history of Surrealism for very long before encountering some variation of the most famous line from Les Chants de Maldoror by the Comte de Lautréamont/Isidore Ducasse: “beautiful as a chance encounter on a dissecting table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella”. Translations vary, as do misquotations; the page above is from the Alexis Lykiard translation where you can also read the surrounding text. The context of the description is seldom mentioned when the quote is used, and reveals that the words are describing the attractiveness of an English schoolboy living with his parents in Paris. The insipid Mervyn is stalked, seduced and finally murdered by the villainous Maldoror. Lautréamont’s metaphor, like so much else in the book, carries a sting in its tail.

2: The Enigma of Isidore Ducasse, 1920

Man Ray, like Mervyn, was a foreigner living in Paris when he created this artwork. The “enigma” may be taken as referring both to the wrapped object (a sewing machine sans umbrella) as well as to the mysterious author of Les Chants de Maldoror, who died at the age of 24 after writing his explosive prose poem, and about whose life little is known. I first encountered Ducasse’s name in art books showing pictures of this piece which is one of the earliest works of Surrealist art. For a young art enthusiast the enigma was more in the name itself: who was this Ducasse, and why was he enigmatic? The original of Man Ray’s piece was subsequently lost, like many of his pre-war sculptures, but may be seen inside the first issue of La Révolution Surrealiste. Editions of the work that exist today are recreations made in the 1970s.

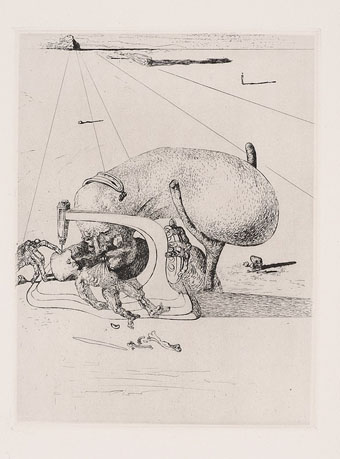

3: An illustration for Les Chants de Maldoror, 1934

Salvador Dalí created 30 full-page etchings and 12 vignettes for an illustrated edition of Lautréamont’s work published by Skira in Paris in 1934. Dalí must have seemed an ideal match for a book whose prose descriptions offer copious atrocities and mutations but, as with many of Dalí’s illustrations, the pictures owe more to his obsessions than to Lautréamont’s text, and could easily be used to illustrate something else entirely. Plate 19 does, however, feature a sewing machine.

4: Electrosexual Sewing Machine, 1935

A Surrealist painting by Oscar Dominguez which emphasises the sexual nature of Lautréamont’s metaphor, or at least the Freudian interpretation of the same. Breton and company took the sewing machine for a female symbol, while the umbrella was male; the dissecting table where their encounter takes place is, of course, a bed.

[In Electrosexual Sewing Machine] the dissection appears to be under way. There is a strange abusive surgery being undertaken, the thread of the sewing machine replaced with blood which is being funnelled onto the woman’s back. The plant itself may even echo de Lautréamont’s umbrella. Domínguez has taken one of the central mantras of Breton’s Surreal universe and has pushed it, through a combination of painterly skill and semi-automatism, in order to create an absorbing and haunting vision that cuts to the quick of the movement’s spirit. (via)

5: Sewing Machine with Umbrellas in a Surrealist Landscape, 1941

More from Dalí who was hired by Fritz Lang to create images for a sequence of drunken delirium in the film Moontide. The commission arrived four years before Dalí’s work for Hitchcock on Spellbound, and if successful might have even dissuaded Hitchcock from hiring Dalí, but Lang left the film once shooting had begun, and his replacement, Archie Mayo, disliked the artist’s contributions. This surviving concept painting seems lazy compared to the Spellbound sequences (which were also trimmed by the ever-interfering David O. Selznick): the colonnade is a bald swipe from De Chirico, while the umbrella-bedecked sewing machine makes clumsy and literal use of the Lautréamont metaphor which is better left as a provocative collision of verbal imagery.

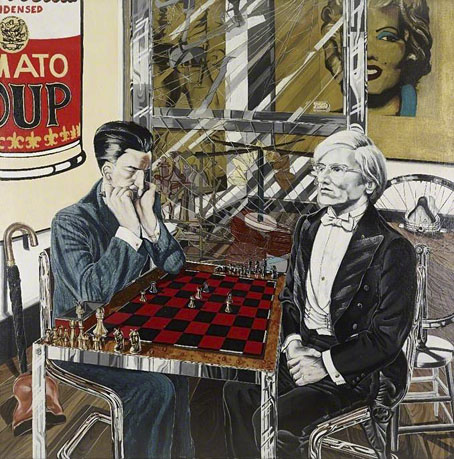

6: “As beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing-machine and an umbrella…”: Andy Warhol and Marcel Duchamp, 1976

A painting by Philip Core, part of a series in which well-known cultural figures (eg: Harold Pinter and Joe Orton) encounter each other in rooms that reflect their works. Core wrote a biography of Andy Warhol, so maybe he knew something that I don’t, but I’d be very surprised if the Pop artist ever played a game of chess in his life, never mind being proficient enough to win so many pieces from the chess-obsessed Duchamp. As for Marcel, he’d raise an eyebrow at that wrongly positioned chess board…

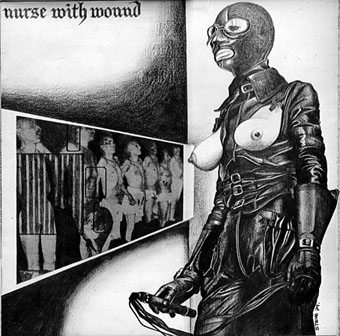

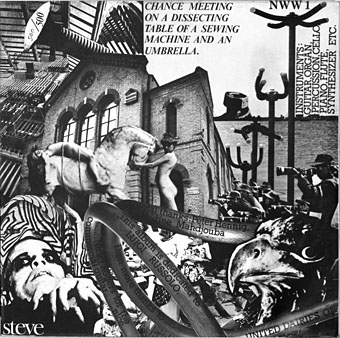

7: Nurse With Wound, 1979

Lautréamont infects another medium. Steven Stapleton’s music group/art project has been infused from the outset by a pranksterish Dada/Surrealist spirit, so the purloining of the metaphor for the title of the first Nurse With Wound album is entirely fitting.

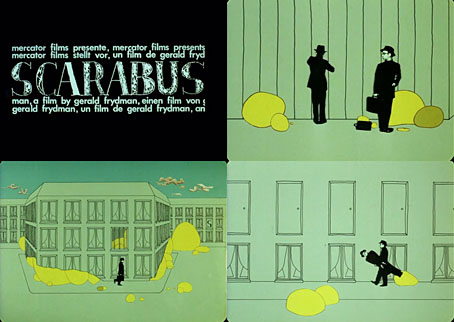

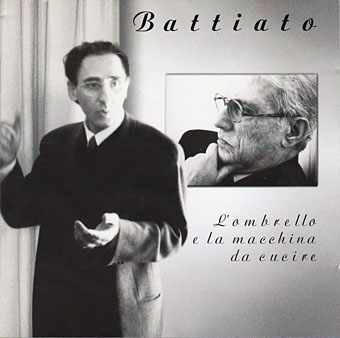

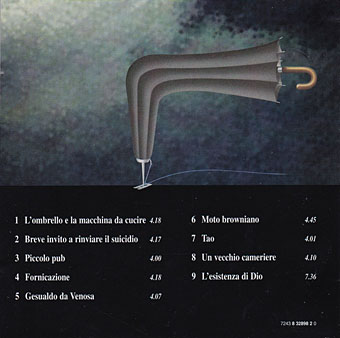

8: L’Ombrello E La Macchina Da Cucire, 1995

Unlike this album by the very prolific Franco Battiato which Discogs describes as “experimental”. The first piece on the album uses the same title as the album, and is anything but experimental, especially compared to the improvised racket created by Nurse With Wound.

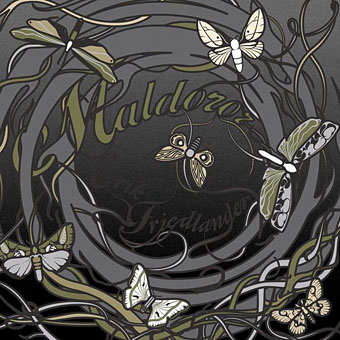

9: Maldoror, 2003

A jazz album by Erik Friedlander which I haven’t heard but which takes its track titles from phrases by Lautréamont.

Do other examples exist? No doubt they do, but the more recent uses of Lautréamont’s words only demonstrate how over-familiarity dulls an effect that was once shocking and original.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Santiago Caruso’s Maldoror

• Jacques Houplain’s Maldoror

• Hans Bellmer’s Maldoror

• Les Chants de Maldoror by Shuji Terayama

• Polypodes

• Ulysses versus Maldoror

• Maldoror

• Books of blood

• Magritte’s Maldoror

• Frans De Geetere’s illustrated Maldoror

• Maldoror illustrated