In today’s post, the recent Mute reissue of the first three albums by Stefan Betke, aka Pole. The photo below is one I took of Herr Betke in a club in Los Angeles in 2005. My old Canon camera was never very good in low-light conditions but a portrait of the artist emerging from gloom seems fitting for music whose reverberant pulses seem to evolve from an equally tenebrous void.

The hundred-year Voyage

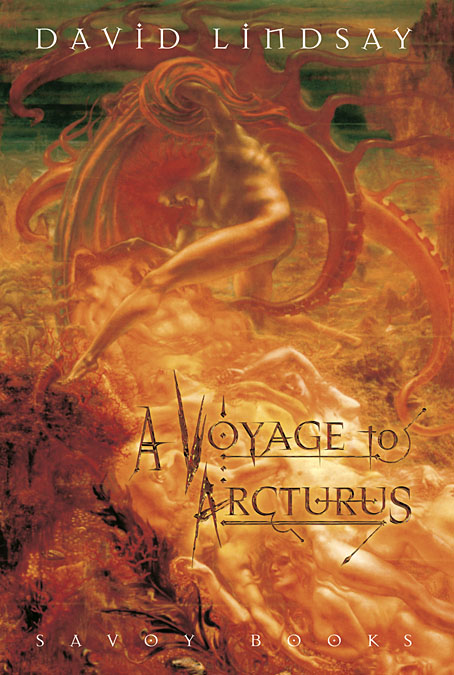

Today’s post at Wormwoodiana reminds me that David Lindsay’s unique novel of philosophical fantasy, A Voyage to Arcturus, was published a hundred years ago today. I designed a lavish reprint for Savoy Books in 2002, an edition which unfortunately used the re-edited text from earlier reprints instead of going to the original publication. This wasn’t done for lack of a first edition, it was more out of ignorance—nobody bothered to look into the history of the text—as well as convenience; Savoy’s earlier reprinting of Anthony Skene’s Monsieur Zenith the Albino had involved many weeks of text preparation, scanning pages from a photocopy of Skene’s very scarce novel, then running the copy through rudimentary OCR software and proofing the result. In Savoy’s slight defence, the reprint of Arcturus did correct a couple of typos that everyone else had missed.

I still think the best feature of my design was the selection of Jean Delville’s remarkable Symbolist painting, The Treasures of Satan (1895), a picture used with the permission of the Brussels Museum of Fine Art. (They supplied us with a print of the painting together with a photo of Delville’s Angel of Splendour (1894) for the back cover.) With the exception of Bob Pepper’s artwork for the 1968 Ballantine paperback, previous reprints of the novel seldom reflected the contents on their covers. I’m no longer happy with the type layout on the rest of the dust-jacket, however, although the front cover looks okay. The Savoy edition included an introduction by Alan Moore, an afterword by Colin Wilson, a collection of philosophical aphorisms by David Lindsay, plus a couple of photos of the author which I don’t think had been published before. Despite its flaws, the book was well-received. The paper was heavier stock than is generally used for hardback fiction which made for a heavy and expensive volume but the edition still sold out.

Penguin are reprinting the novel next year in an edition which continues the tradition of unsuitable cover art. According to Lindsay site The Violet Apple the figure on the cover is from an illustration for a Dostoevsky novella, so what is it doing on Lindsay’s book? Cover art aside, the novel is in a class of its own, and very highly recommended.

Previously on { feuilleton}

• The art of Bob Pepper

• Masonic fonts and the designer’s dark materials

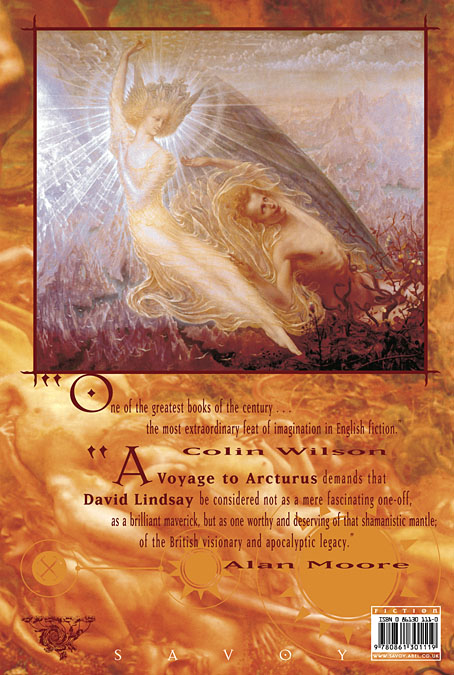

The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse

Among the weekend’s viewing was the third and final film in Fritz Lang’s Mabuse cycle, The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse (1960). This was also Lang’s final feature, made after his return to Germany in the late 1950s, and another film of his that for many years I knew only as an impossible-to-find title. I’d read about the Mabuse series in Lotte Eisner’s study of Lang’s career even before the name and character was co-opted by Propaganda for their first single in 1984, but the only films of Lang’s that ever used to appear on TV were the Hollywood features or, if you were lucky, a poor print of Metropolis. Mabuse was a source of fascination for the way the character connected the beginning and ends of the director’s career, as well as being a German take on the Moriarty-like super-criminal. The first film in the series, Dr Mabuse, the Gambler (1922), condenses the corruption of Weimar Germany into a potent physical icon, while the sequel, The Testament of Dr Mabuse (1933), reflects the fevered moment when real super-criminals were taking control of the nation. The Nazis were sufficiently discomforted by Testament to ban it shortly after its release.

Cornelius the psychic with insurance salesman Hieronymus B. Mistelzweig and police inspector Kras.

The Thousand Eyes of Dr Mabuse appeared just as new super-villains were emerging to oppose James Bond and his imitators. One of Bond’s early adversaries, Auric Goldfinger, was portrayed on screen by Gert Fröbe who appears here on the opposite side of the law as homicide inspector Kras. Fröbe’s tenacious policeman is one of the few fixed points in a plot filled with twists and deceptive identities. Assassinations and double-crosses are a staple of this type of thriller but Lang also gives us an early example of electronic surveillance in a contemporary setting, together with a séance that harks back to a similar scene in the first Mabuse film. The séance is an unusual touch in a story otherwise devoid of similar moments, prompted by the film’s most mysterious character, Cornelius the blind psychic. With an appearance reminiscent of the late Karl Lagerfeld, Cornelius is an overt throwback to Lang’s pre-war films, many of which hinted at the mystical or supernatural even when such hints seemed unnecessary; Rotwang, the robot-builder in Metropolis (played by the original screen Mabuse, Rudolph Klein-Rogge) is a mechanical genius who just happens to live in a house more suited to an alchemist, with a huge inverted pentagram on one of its walls. The sinister motives of Cornelius aren’t so baldly stated but his consulting room is lavishly decorated with astrological diagrams. The psychic, together with the criminals and the police inspector, create a problem common to films of this kind in which the more colourful characters generate greater interest for the viewer than do the romantic leads. After a succession of breathless opening scenes, Thousand Eyes sags a little while wealthy industrialist Henry Travers (Peter Van Eyck) is getting to know Marion Menil (Dawn Addams), a woman he rescues from a suicide attempt. The film also lacks the subtext of the earlier episodes, although Mabuse’s scheme turns out to be diabolical enough for any of James Bond’s Cold War enemies.

The séance.

Weekend links 534

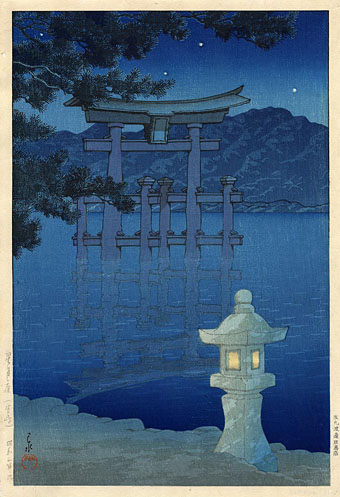

Beautiful night – moon and stars, Miyajima Shrine (1928) by Hasui Kawase.

• One announcement I’d been hoping for since last summer was the news of a second box of Tangerine Dream albums to follow the excellent In Search Of Hades collection. The latter concentrated on the first phase of the group’s Virgin recordings, up to and including Force Majeure. This October will see the release of a new set, Pilots Of Purple Twilight, which explores the rest of the Virgin period when Johannes Schmoelling had joined Froese and Franke. Among the exclusive material will be a proper release of the soundtrack for Michael Mann’s The Keep (previously a scarce limited edition), together with the complete concert from the Dominion Theatre, London. Also out in October, Dark Entries will be releasing a further collection of recordings from the recently discovered tape archive of Patrick Cowley. The new album, Some Funkettes, will comprise unreleased cover versions, one of which, I Feel Love by Donna Summer, is a cult item of mine that Cowley later refashioned into a celebrated megamix.

• “Did you know that Video Killed The Radio Star was inspired by a JG Ballard story?” asks Molly Odintz. No, I didn’t.

• Casey Rae on the strange (musical) world of William S. Burroughs. Previously: Seven Souls Resouled.

• “And now we are no longer slaves”: Scott McCulloch on Pierre Guyotat’s Eden Eden Eden at fifty.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Frank Jaffe presents…Dario Argento and his world of bright coloured blood.

• At Wormwoodiana: The Serpent Calls. Mark Valentine on a mysterious musical instrument.

• At Spoon & Tamago: Long-Exposure Photographs of Torii Shrine Gates by Ronny Behnert.

• Mix of the week: mr.K’s Soundstripe vol 4 by radioShirley & mr.K.

• Rising sons: the radical photography of postwar Japan.

• The illicit 1980s nudes of Christopher Makos.

• RIP Diana Rigg.

• Garden Of Eden (1971) by New Riders Of The Purple Sage | Ice Floes In Eden (1986) by Harold Budd | Eden (1988) by Talk Talk

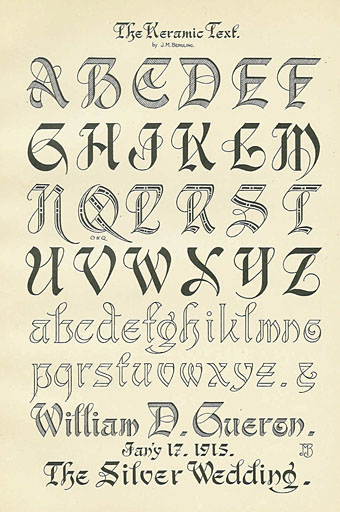

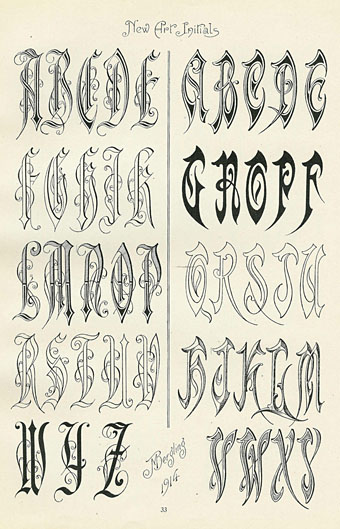

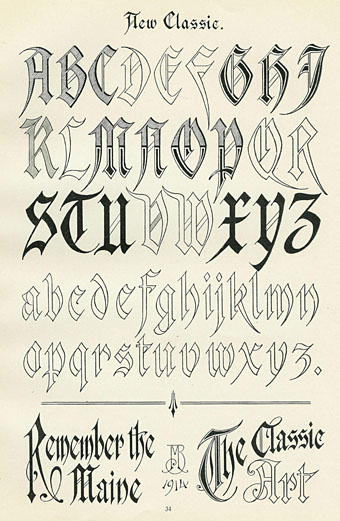

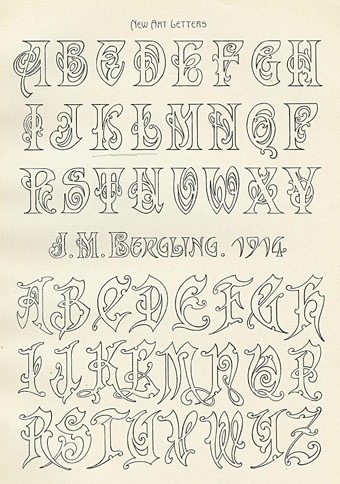

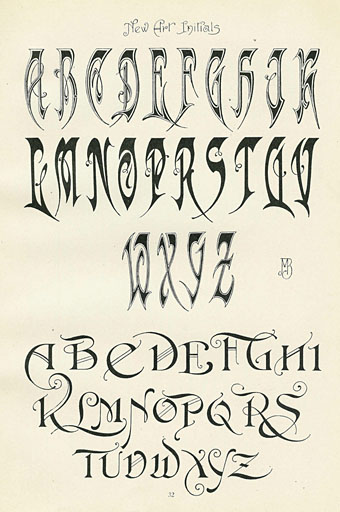

Bergling’s Art Alphabets

Old type catalogues seldom contain any unusual typefaces so you have to look to craft books for original letterforms. Art Alphabets and Lettering (1914) is an American book for artists and sign painters written and designed by JM Bergling which contains several pages of novel designs among its more familiar typefaces. Bergling evidently had a flair for alphabet design, there are more unique examples here than you’d usually find in a book of this kind, and Bergling’s letterforms are consistently stylish and inventive. In addition to providing a number of spiky variants on the Art Nouveau style (which by 1914 was going out of fashion), he also found time to draw his own version of a 19th-century staple, the Rustic Alphabet. There are two copies of the book at the Internet Archive: a complete one and an incomplete one, the latter volume possibly being a later printing since it contains a number of pages not included in the former.