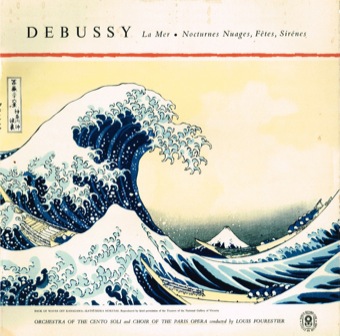

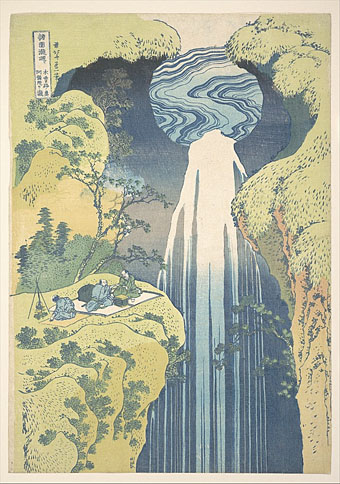

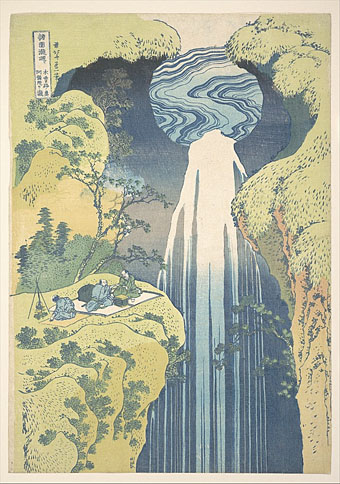

The Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the Kisokaido Road. From the series A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces (c. 1832) by Hokusai.

• New music: In Love With A Ghost by Kevin Richard Martin (aka Kevin Martin, The Bug, etc), a preview from his forthcoming alternative score for Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972). In other hands I’d probably dismiss a further addition to the trend of creating new scores for films that don’t require them. Tarkovsky’s film certainly doesn’t need any new music, and we’ve already had an album-length homage from Ben Frost & Daníel Bjarnason. But I like Martin’s sombre atmospherics so he gets a pass with this one.

• “[Pauline] Oliveros wrote a piece for the New York Times in 1970 titled And Don’t Call Them Lady Composers, focusing on the difficulties of women being noticed and taken seriously in her field. It’s still online and could have been written yesterday.” Jude Rogers on Sisters With Transistors, a documentary about women in electronic music. Madeleine Siedel interviewed Lisa Rovner, the film’s director. Watch the trailer.

• Submissions to the 16th number of Dada journal Maintenant will be open at the beginning of October, 2021, following an announcement of the theme of the new issue in September. All you would-be (or actual) Dadaists out there have the summer to plot your potential contributions.

Our reverence for originals takes an absurdly extreme form in the recent craze for NFTs (non-fungible tokens), where collectors and traders spend huge sums of money on unique ‘ownership’ of a digital artwork that anyone can download for free. Since there’s no such thing as the original of a digital file, the artist can now certify the file as the one and only ‘original copy’, and make a fortune. Time will tell whether this is a transient fad or a new way of establishing the feeling of a relationship to the mind of the digital artist.

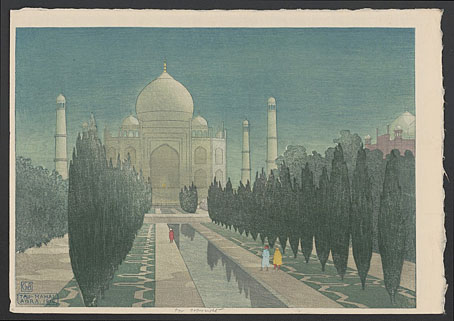

But our reverence for originals isn’t universal. Treating the original as special and sacred is a Western attitude. In China and Japan, for example, it’s acceptable to create exact replicas, and these are valued as much as the original—especially because an ancient original might degrade over time, but a new replica will show us how the work looked originally. And, as mentioned, there are studios in China where artists are employed to create fakes. Perhaps our culture teaches us to respond to artworks by inferring the mind behind the art.

“Works of art compel our attention—but can they change us?” asks Ellen Winner

• “What Don basically did here is find a series of one or two bar riffs, or parts, that he liked, have me write them down, and then say, in essence, ‘make something out of this’.” John French (aka Drumbo) recalls the making of Trout Mask Replica.

• From 1988 (and relevant this week because I’m reading a Pynchon novel): Thomas Pynchon’s review of Love in the Time of Cholera.

• Andy Thomas on fusion legend Ryo Kawasaki, pioneer of the synth guitar.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Dimitri Kirsanoff Day.

• Gareth Jones’ favourite music.

• RIP Monte Hellman.

• The Sea Named “Solaris” (1978) by Tomita | Solaris (2014) by Docetism | Solaris Return (2019) by Jenzeits