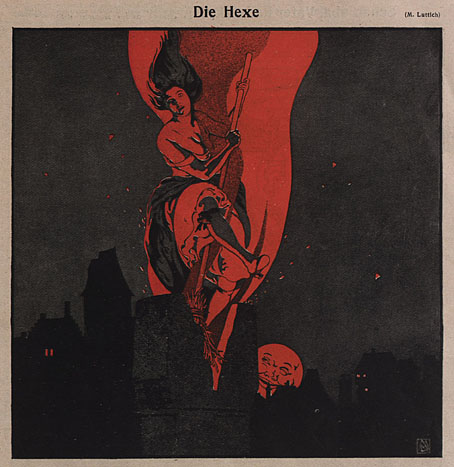

The Witch (1920) by Mila von Luttich for Die Muskete.

• “One thing that used to annoy Geff in particular—I don’t think Sleazy cared so much—was that the gay press hardly ever paid any attention to Coil. It really was the cliché of, if you’re making disco bunny or house music then you might get covered in the gay press, but if you’re not doing something that appeals to that rather superficial aesthetic, which was the hallmark of the gay scene, they didn’t even deign to glance at you.” Stephen Thrower talking to Mark Pilkington about Love’s Secret Domain by Coil, and touching on an issue that I’ve never seen referred to outside the occasional Coil interview. Coil’s sexuality was self-evident from their first release in 1984 but they always seemed to be too dark and too weird for the gay press, and for the NME according to this interview.

• “Gorey collected all sorts of objects at local flea markets and garage sales—books, of course, though also cheese graters, doorknobs, silverware, crosses, tassels, telephone insulators, keys, orbs—but he especially loved animal figurines and stuffed animals.” Casey Cep on Edward Gorey’s toys.

• Last week it was a giant cat opposite Shinjuku station; this week at Spoon & Tamago there’s a giant head floating over Tokyo.

• DJ Food delves through more copies of The East Village Other to find art by underground comix artists (and Winsor McCay).

• New music: My Sailor Boy by Shirley Collins, and Vulva Caelestis by Hawthonn.

• “€4.55m Marquis de Sade manuscript acquired for French nation.”

• At Dangerous Minds: The Voluptuous Folk Music of Karen Black.

• At Greydogtales: Montague in Buntlebury.

• Aaron Dilloway‘s favourite music.

• Toys (1968) by Herbie Hancock | Joy Of A Toy (1968) by The Soft Machine | Broken Toys (1971) by Broken Toys