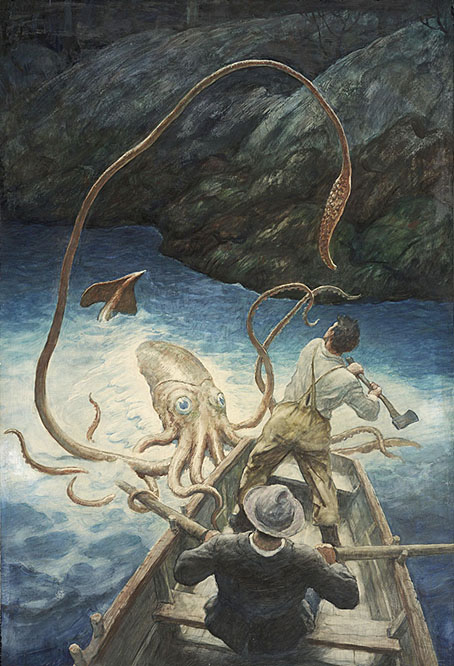

The Adventure of the Giant Squid (c.1939) by NC Wyeth.

• Mix of the week is a superb XLR8R Podcast 860 by Kenneth James Gibson. Elsewhere there’s DreamScenes – July 2024 at Ambientblog, and Deep Breakfast Mix 267 at A Strangely Isolated Place.

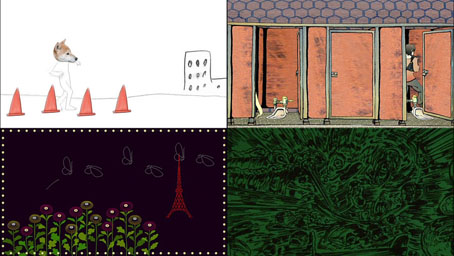

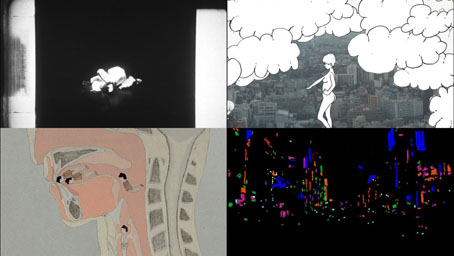

• A trailer for a restored print of Time Masters (1982), the second animated feature by René Laloux, with character designs/decor by Moebius. Now do Gandahar.

• Coming soon from Strange Attractor: Music From Elsewhere: Haunting Tunes From Mythical Beings, Hidden Worlds, and Other Curious Sources by Doug Skinner.

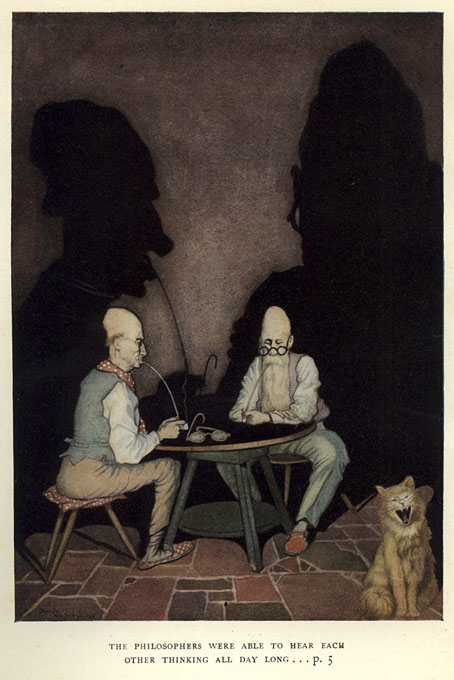

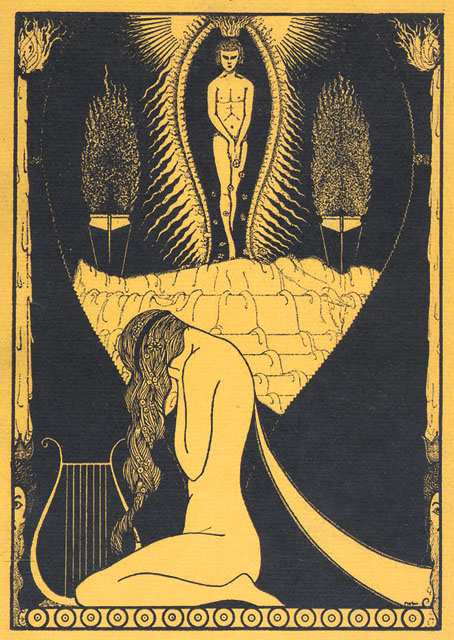

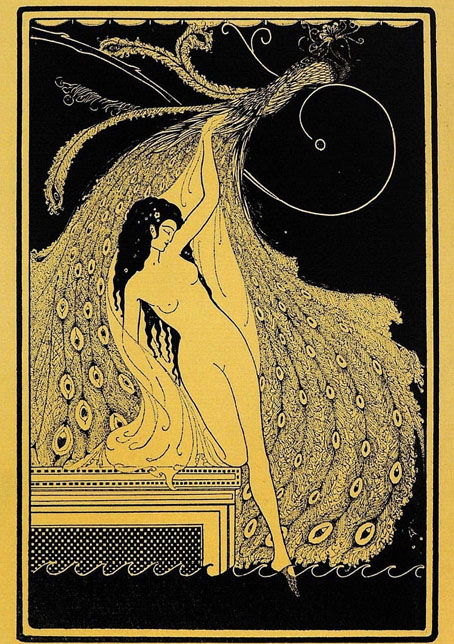

Not only a prolific lyricist, Lovecraft considered his main vocation to be poetry. And at its best, his verse can be judged an apt expression of his philosophical vision, in which cosmic horror embodies the predicament of all sentient beings in a meaningless universe. That Lovecraft’s poetry never reaches the heights attained by such Modernists as T.S. Eliot or Ezra Pound should not diminish the fact that his is verse that, in the most archaic of ways, advances a startlingly modern metaphysic, a poetic encapsulation of what Thomas Ligotti in The Conspiracy Against the Human Race describes as an affirmation that the universe is a “place without sense, meaning, or value.” Lovecraft, with his antiquated prosody and his anti-human ethics, presented readers with a type of counter-modernist poetry. Ironically, he is the radical culmination of William Carlos Williams’s injunction of “No ideas but in things;” he is an author for whom there are only things. Graham Harman in Lovecraft and Philosophy describes Lovecraft as a “violently anti-idealist” who “laments the inability of mere language to depict the deep horrors his narrators confront.” Unpleasant stuff, for sure. It is verse that at best exemplifies something that controversial poet Frederik Seidel called for in the Paris Review: “Write beautifully what people don’t want to hear.”

Ed Simon on The Unlikely Verse of HP Lovecraft

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, by HP Lovecraft.

• At Spoon & Tamago: An ethereal bubble emerges from a Japanese townhouse.

• New music: The Head As Form’d In The Crier’s Choir by Sarah Davachi.

• Mabe Fratti’s favourite albums.

• Bubble Rap (1972) by Can | Bubbles (1975) by Herbie Hancock | Reverse Bubble (2014) by Air