Jetpac (1983) by Ultimate Play The Game. Lunar Jetman was the superior sequel but Jetpac had the better loading screen.

• RIP Clive Sinclair. Products made by Sinclair Research Ltd. were among the first electronic gadgets I owned: the Sinclair Scientific calculator which compelled you to learn Reverse Polish notation before you could use it; the ZX Spectrum computer, of course; and the pocket TV that came bundled with the computer, a machine with such feeble reception that it only ever worked outdoors. I’ve still got my Spectrum computer, and it still worked the last time I plugged it in although it’s hardly worth keeping when emulators proliferate. Spectacol for Android is a good example of the latter. Related: World of Spectrum; the early stages of the Spectrum design process by Sinclair designer Rick Dickinson; XL-1 by Pete Shelley, electro-pop with Spectrum-generated lyrics and graphics.

• Mixes of the week: A Lee “Scratch” Perry tribute mix by Dennis Bovell, and Blood Tide Station 1: Breakaway plus Blood Tide Station 2: Force of Life by The Ephemeral Man.

• “It’s not an easy time to be daring,” says Dennis Cooper, talking to Barry Pierce about his new novel, I Wished.

• London under London: Adam Zamecnik interviews Tom Chivers about searching for London’s lost rivers.

• New music: Ode To The Blue by Grouper, and A Shadow No Light Could Make by Nathan Moody.

• At Public Domain Review: 700 years of Dante’s Divine Comedy in art.

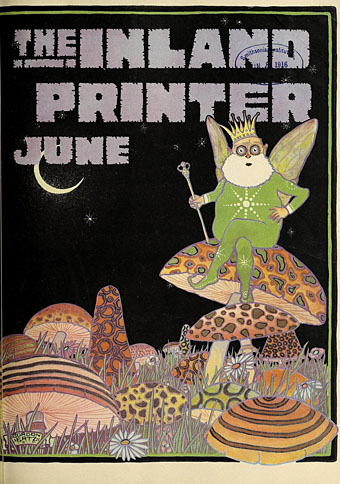

• At Wormwoodiana: The Mushroom Man—A Note on EC Large.

• DJ Food trips out with a collection of psychedelic drug posters.

• Nodnol (1969) by The Spectrum | Spectrum (1969) by The Tony Williams Lifetime | Spectrum (1973) by Billy Cobham