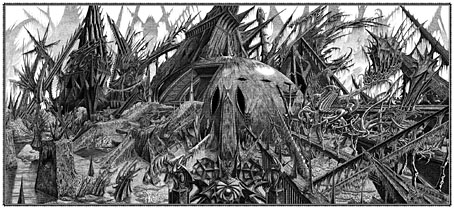

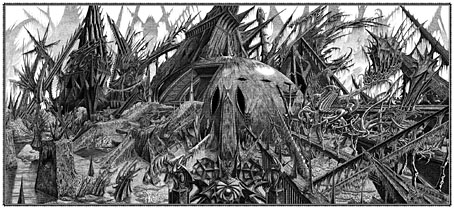

Then, driven ahead by curiosity in their captured yacht under Johansen’s command, the men sight a great stone pillar sticking out of the sea, and in S. Latitude 47°9′, W. Longitude 126°43′, come upon a coastline of mingled mud, ooze, and weedy Cyclopean masonry which can be nothing less than the tangible substance of earth’s supreme terror—the nightmare corpse-city of R’lyeh, that was built in measureless aeons behind history by the vast, loathsome shapes that seeped down from the dark stars. There lay great Cthulhu and his hordes, hidden in green slimy vaults and sending out at last, after cycles incalculable, the thoughts that spread fear to the dreams of the sensitive and called imperiously to the faithful to come on a pilgrimage of liberation and restoration.

HP Lovecraft, The Call of Cthulhu (1928)

Behold the fruits of a more benevolent pilgrimage of liberation and restoration. It was just over a year ago that I decided to draw an exact replica of the R’lyeh triple-spread from my comic-strip adaptation of The Call of Cthulhu, the intention being to make the picture available as a poster-sized print once I had a print-ordering system in place. The picture may now be purchased here as a giclée print on Hahnemüle Pearl art paper. This is a big picture (870.46 x 401.15 mm or 34.27 x 15.793 ins), and unlike my other Etsy prints I’m afraid there won’t be a half-size version which means the price will remain relatively high. I’m also keeping it as a black-and-white piece despite the temptation to create a tinted version.

And so to the obvious question: why did I want to redraw a large and very detailed piece of art in the first place? Pull up a weed-festooned Cyclopean bollard and I’ll explain…

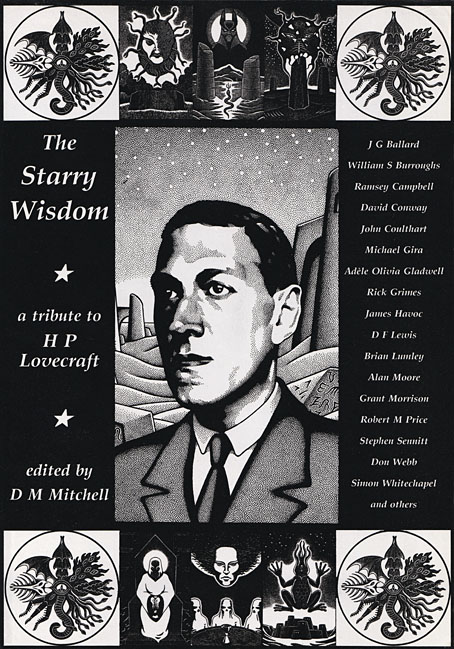

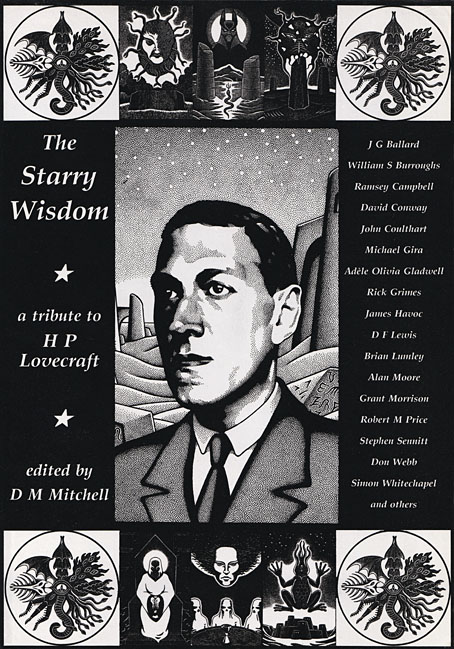

Creation Books, 1994. Cover art by Peter Smith.

I spent 17 months drawing The Call of Cthulhu, from January 1987 to May 1988, using my preferred media of the time, a 0.2 mm Rotring Variant pen on A3 sheets of Daler cartridge paper. The story took its time getting into print but it was eventually published in 1994 by Creation Books as part of The Starry Wisdom, a collection of Lovecraftian fiction edited by DM Mitchell. I was very pleased to be represented in the book but the pleasure turned to dismay when it transpired that all the artwork had vanished after the printing was done. Or almost all the artwork… To this day I don’t know whether the drawings by other artists suffered the same fate, but my Cthulhu pages disappeared along with the anatomical cross-section and the Yuggoth collage that I created specially for the collection. I still don’t know what really happened either, whether the drawings were stolen (possible), thrown away deliberately (unlikely), or thrown away accidentally (also possible). The lack of resolution to the whole business is partly my fault. Losing all that art was a painful thing to consider, and I couldn’t accuse the printer of anything when nobody could say what had happened (I was in the Creation office during one of the phone conversations between publisher and printer). The printer was also located in the middle of a rural county somewhere so journeying there would have been difficult for this non-driver, as well as being pointless if they could only tell me what I knew already. Time passed and I did my best to put the whole episode behind me.

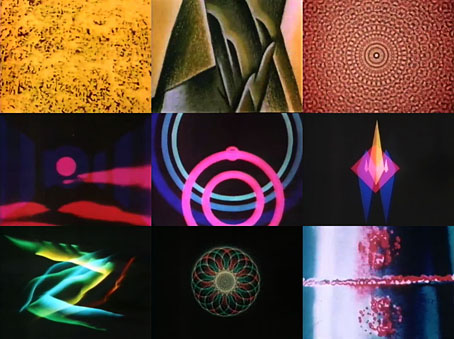

Drawing technology then and now: the Variant pen I used throughout the 1980s and the Wacom stylus I use today. That Variant nib is so fine that I have a faint ink dot tattooed on one of my knuckles from where I accidentally stabbed it into my hand. The Wacom pen looks stubby in comparison but is capable of drawing equally fine lines and much more besides.

On the plus side (there was one), the printer had done a good job of half-toning the artwork, so even though the Starry Wisdom pages are rather small the detail in the drawings is still evident. And I also had a complete set of photocopies of the A3-sized originals. I’d been working for Savoy Books since 1989 during which time making photocopies of new drawings had become second nature. Since 1994 this set of copies has become the original art for the Call of Cthulhu strip, rather like the surviving prints of Murnau’s Nosferatu which are all that anyone can see of his film today. The analogy is an apt one since it also extends to picture quality. Just as silent films always look their best when they’ve been restored from the camera negative, my Rotring drawings really need to be reproduced from the originals. The 0.2 mm pen that I insisted on using throughout the 1980s was too fine for the photocopy machines of the time, especially when my shading was so densely rendered that I might as well have been using a pencil. This isn’t so much of a problem if the pages are being reduced in size but it became one last year when I had the idea of making a print of the R’lyeh panorama that would be the same size as the original drawings. Giclée printing is an ink-jet process that reproduces fine detail with great accuracy, so while I could make full-size prints of the Cthulhu pages they’d never look better than what they were, photocopies that hadn’t fully captured the fine lines of the drawings. This wasn’t the only problem.

Continue reading “Resurrecting R’lyeh”