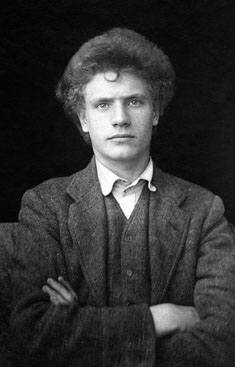

Today is the 50th anniversary of the death of one of my favourite artists, Austin Osman Spare.

Like many people in the 1970s, I was introduced to the work of Austin Spare by Man, Myth and Magic, a seven volume “illustrated encyclopedia of the supernatural” published weekly in 120 112 parts by Purnell. My mother was a Dennis Wheatley reader so we had a couple of occult paperbacks in the house, among them one of William Seabrook‘s accounts of voodoo in Haiti and a copy of Richard Cavendish’s wonderful magical primer, The Black Arts, (later retitled The Magical Arts). Cavendish had been chosen as editor of Man, Myth and Magic and included occultist and writer Kenneth Grant on his editorial staff, a decision that gave the book’s producers access to Grant’s collection of Spare pictures. In a rather bold move, they launched Man, Myth and Magic in 1970 with a detail of a Spare drawing on the cover, a work often referred to as The Elemental although the authoritative Spare collection, Zos Speaks has it titled as The Vampires are Coming. It’s a shame that AOS didn’t live for a few more years to see this; after labouring in poverty and obscurity for most of his life he would have found his work flooding Britain, with this first issue on sale all over the country and the cover picture being pasted on billboards and sold as posters. It’s possible there were even television adverts for the book (although I don’t recall any), since there usually were for expensive part works like this.