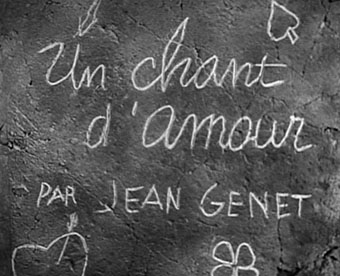

Genet’s gay classic at Ubuweb.

Un Chant d’Amour, 1950, 269 mb (AVI)

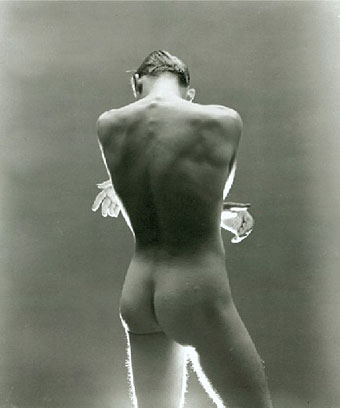

Packed with shots of full frontal hard ons, masturbation, and extreme close ups of sweaty feet, armpits and thighs, Jean Genet’s only film is confrontingly explicit. Though no sex takes place, the erotic factor of Un Chant d’Amour is off the scale, and makes for a sensational viewing experience that feels like watching porn. As well, as a twenty-five minute black and white avant garde short, it’s everything but commercial, and it was even abandoned by its director who, à la George Michael, disowned it in the mid seventies on the grounds that he had reached a far more sophisticated plateau of artistic expression, and was embarrassed by this crude early work. No wonder then, that Un Chant D’Amour has been banned, censored and blacklisted ever since its 1950 release.

This is quite a shame, for apart from being an excellent and extremely horny short film, Un Chant d’Amour is quite the hidden treasure, an underviewed and lushly romantic avant-garde tribute to yearning and desire, and and a frustrating glimpse of what might have been if Genet had kept making films.

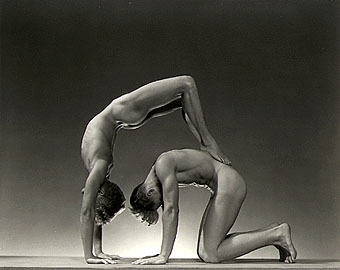

Stuck in airless and solitary prison cells (somewhere in Algeria, presumably), sexy inmates drive themselves to the edge with obsessive erotic longing for each other. Almost mad from solitude and longing, they blow cigarette smoke through mini glory holes, and writhe against thick concrete walls, knowing their man is on the other side. A sexually suspect guard spies on them, one by one, peep show style, and they sometimes notice, and perform for him. He gets so worked up he breaks into a cell, whips the inmate, and gets him to fellate his gun. Symbolism and dream sequences abound, but are hard to distinguish from the narrative proper as Genet’s use of repetition, ritual, and stylised movement is unrelentlingly hypnotic.

Un Chant d’Amour’s resonance is mostly due to images that would never make the cut of modern pop culture, certainly not a modern commercial film. Saying that most gay-interest films pale in comparison, then, is unfair. However, Genet’s sensuous presentation makes his two central characters’ almost insane cravings tangible and heartfelt. No amount of dialogue compensates, and furrow-browed pleas for tolerance and happiness drag things in the opposite direction fast. The fantasies of Un Chant D’Amour involve smoke, flowers, dance and forests as well as hair, sweat and muscle. This rocking back and forth between lush romance and salty carnality is a little dizzying, but masterfully (unknowingly?) evocative. By comparison, most other gay films look like tupperware parties, gatherings of politically activated animatronic eunuchs.

Like The Deep End, Un Chant d’Amour taps into elemental energies and ignores politics and socialisation, and as a result comes closest to capturing (pre-rainbow flag) “gay” on screen.

Review by Mark Adnum

www.outrate.net