Alaska Melting, vinyl-only release

by my favourite electronic artist.

Rembrandt’s vision

The Netherlands celebrate four hundred years of Rembrandt’s genius.

While looking around for links I noticed this story for the first time:

Margaret S. Livingstone and Bevil R. Conway, neurobiologists at Harvard Medical School, say Rembrandt’s many self-portraits reveal that his eyes are focused in slightly different directions, depriving him of the “stereo” effect that makes vision three-dimensional. As a result, they argue, Rembrandt would have struggled with depth perception – though he may never have known he had a vision defect.

Rembrandt’s flat world view may have helped him more precisely capture reality on a flat canvas, where painters create the illusion of three-dimensions through techniques such as shading. In fact, Livingstone and Conway say that visual artists are far more likely to be “stereoblind” than the general public, suggesting that limited depth perception may actually be an advantage over normal sight.

“Art teachers often instruct students to close one eye in order to flatten what they see,” the researchers write in today’s New England Journal of Medicine, explaining their theory about Rembrandt. “Stereoblindness might not be a handicap – and might even be an asset – for some artists.”

Similar assertions from doctors about conveniently dead artists surface from time to time; we had Michelangelo suffering from Asperger’s recently and I recall a story about Shakespeare having a brain tumour based solely on scrutiny of very vague portraits. The Rembrandt story is significant for me because my eyes have always been mis-aligned and I don’t see stereoscopically. I have permanent double-vision as a result, something people are always surprised to hear, although I only notice this when I think about it. My brain treats the mis-aligned (and weaker) data from my right eye as redundant information and so ignores it.

The point is, whether Rembrandt had a similar defect or not (and I’m sceptical; how can you be so sure by looking at a few paintings?), it’s very difficult, if not impossible, to judge what effect this has on artistic ability without conducting a mass survey. Even then I doubt that you’d discover much. The doctors in this case want to imply that Rembrandt’s damaged eyesight gave him an extra edge with regard to depth perception but I find this incredibly difficult to demonstrate with any degree of certainty. What gives Rembrandt more of an edge (and keeps us looking at his work) is his exceptional drawing skill and peerless mastery of the oil medium, something that’s partly innate talent but mostly prodigious ability and the result of years of labour. Whatever assistance stereoblindness might lend him would be a very small thing next to this combination of natural gifts and hard work.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• “One measures a circle, beginning anywhere?”

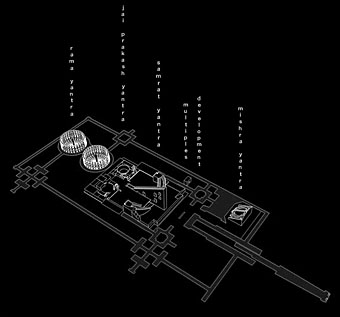

The Garden of Instruments

The Garden of Instruments

by Paul Schütze and Kevin Pollard.

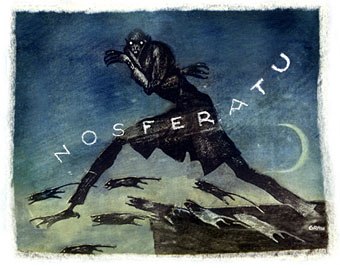

Nosferatu

Poster design by Albin Grau.

Friedrich Murnau’s Nosferatu, A Symphony of Horror (1922) isn’t the first horror film but it’s certainly the first truly effective one which is why it’s been so influential over the years, inspiring a remake by Werner Herzog (1979), the vampire’s appearance in Salem’s Lot (1979), Coppola’s Dracula (1992), and a fictionalised account of its creation in Shadow of the Vampire (2000).

The Internet Archive have a copy available as a free download. If you’ve never seen it then this is your chance since silent films rarely turn up on TV. Many early films exist in multiple versions due to the vagaries of film storage (different cuts, decaying prints, etc). Nosferatu was nearly destroyed altogether after a successful lawsuit by Bram Stoker’s widow, Florence, which means that all the prints are in a less than satisfactory condition. My own favourite is the BFI edition (which DVD now seems to be deleted), taken from the definitive “Bologna” restoration, with scenes tinted throughout (as silent films often were) and with a tremendous new score by Hammer composer James Bernard.

Murnau went on to make better films but Nosferatu retains an uncanny power owing to the rare combination of the director’s technical brilliance and Albin Grau’s fabulous vampire design, worlds away from Stoker’s sinister aristocrat. This is the place where cinema showed it could fully compete with horror fiction by summoning its own archetypes from the recesses of the imagination.

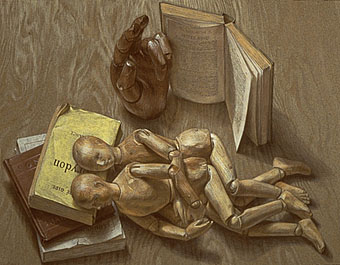

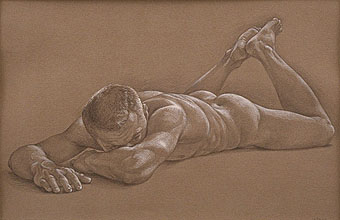

The art of Paul Cadmus, 1904–1999

Manikins (1951).

Male Nude (1954).

Good gallery of his often enigmatic paintings here.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive