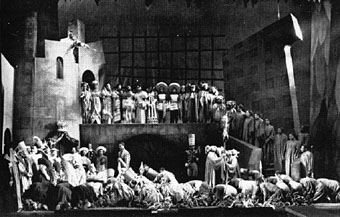

In 1936, whilst the UK was celebrating the new De La Warr Pavilion, and exciting artistic movement was reaching its close in New York—the Harlem Renaissance. A significant event within of this movement was an all-black African American version of Macbeth, presented by The Federal Theatre Project at the New Lafayette Theatre, Harlem and directed by writer and actor Orson Welles. This production became known as ‘Voodoo Macbeth‘.

There are many things that were remarkable about this unique and innovative project. The play was one of the first explorations of a modern and diasporic spin on the Shakespearian tale. It was also the point at which Welles was introduced to John Houseman, which then led to the formation of the Mercury Theatre Company that produced seminal works such as the War of the Worlds and Citizen Kane. Furthermore, the ‘Voodoo Macbeth‘ production displayed visual and aural motifs using lighting, stage design and overlapping sound which became signature elements to Welles’s later film projects.

The essence, spirit, and cross-artform experimentality of ‘Voodoo Macbeth‘ is the basis for a contemporary art, film and performance season at the De La Warr Pavilion and has been named after the production. This unique project looks at the historical and contemporary dialogue that Welles’s work had and still has with performance, film and visual art.

The curatorial concept of the De La Warr Pavilion’s exhibition Voodoo Macbeth focuses on the debate and the ideas around Welles’s unique and defining aesthetic which continues to attract much critical attention. The exhibition suggests that Welles’s approach has informed the work of many contemporary artists working in film today.

Both the historical and contemporary context of Voodoo Macbeth are explored within the exhibition and wider season of events. Original works by Orson Welles are presented alongside those of his contemporaries including Jean Cocteau, Jacques Tourneur and Lee Miller. These artists were working with film and photography during the period of the 1940s onwards and have a shared concern in exploring visual ideas and motifs around the idea of an ‘expansive frame’. As artists, they blurred the boundaries between visual art, theatre, literature and film, to produce lyrical and poetic visual works.

Work by contemporary artists within the exhibition have been selected on the basis that their work embodies the artistic narrative and the spirituality of Welles’s use of light, dark and spatial composition. The exhibition includes work by Phyllis Baldino, Glenn Ligon, Steve McQueen, Mitra Tabrizian and Kara Walker. In this context, Voodoo Macbeth explores how, for artists today, the genre and its relationship to installation practice in performance, film, sound and visual art is an important part of the process. Importantly, they do not mimic the formalist structure of film, painting and sound but endeavour to embed these works with elements of popular culture, critique and humour. Like Welles, who was a masterful story teller, these artists have developed works which take on the character of an intimate 21st century tale. Unlike Welles, these tales are tailor-made, for a gallery audience to explore and enjoy.

Produced by the De La Warr Pavilion in association with Brighton Photo Biennial and curated by associate curator David A Bailey in collaboration with BPB curator 2006 Gilane Tawadros.

The Galleries are open 10am–6pm except on Christmas Eve (closing

at 5pm), Christmas Day (closed all day) and New Year’s Eve (closing at 3pm). Free.

Voodoo Macbeth, Oct 7th–Jan 7th.

The Voodoo Macbeth exhibition is a part of the Brighton Photo Biennial, for more details on the BPB please visit their website www.bpb.org.uk, or contact them via the details below.

Biennial Office

University of Brighton

Grand Parade

Brighton BN2 0JY

Tel: +44 (01)273 643 052

Email: mail@bpb.org.uk