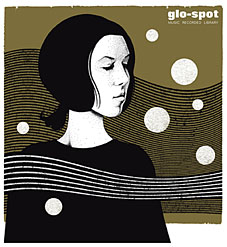

Well…new for us. Glo Spot Records have reissued Psyche-Delia‘s scarce KPM album, Electrosonic (1972), in an edition that will quickly become as scarce itself: 500 copies on green vinyl.

Order it (or hear clips) from Boomkat.

The great BBC documentary about the Radiophonic Workshop, Alchemists of Sound, can now be found on YouTube. Lots of archive footage of Delia and her collaborators showing how they extracted extraordinary sounds from primitive equipment.

Delia Derbyshire is best known as the woman who created the sound of the original Doctor Who theme. This one piece is so globally famous that it has overshadowed the wide ranging work of one of the most creative women working in the 1960s and ’70s. Delia collaborated with many of the most significant figures of the era and was admired by many more. Her story involves such names as Paul McCartney, Yoko Ono, Pink Floyd, Anthony Newley, Frankie Howerd and The Rolling Stones, in addition to work with the National Theatre, seminal electronic innovators and, of course, the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop. Since her death in 2001, Derbyshire has gained cult icon status and her influence over artists who weren’t even born when she made some of her groundbreaking recordings has never been stronger. John Cavanagh (BBC Radio, Phosphene, author of The Piper at the Gates of Dawn etc. etc.) has found a rare album Delia recorded with Brian Hodgson (the man who created the sound of the TARDIS) and Australian mood music composer (who also scored some Doctor Who episodes) Don Harper in 1972. This was originally an lp of what is known as library music and was only made available to film, tv and radio organizations when originally issued. Cavanagh has licensed these recordings and the album—Electrosonic—will be released commercially for the first on his Glo-Spot label.

Electrosonic (1972)

Label: KPM

Cat: KPM1104

1 Quest

2 Quest – fast

3 Computermatic

4 Frontier of Knowledge

5 The Pattern Emerges

6 Freeze Frame

7 Plodding Power

8 Busy Microbes

9 Liquid Energy (a)

10 Liquid Energy (b)

11 No Man’s Land

12 Depression

13 Nightwalker

14 Electrostings

15 Electrobuild

16 Celestial Cantabile

17 Effervescence

18 The Wizard’s Laboratory

19 Shock Chords

Previously on { feuilleton }

• A playlist for Halloween

• Ghost Box