Secret Dream (2005), giclee print with oil paint, gold and mixed media.

Via Casual In Istanbul.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

Secret Dream (2005), giclee print with oil paint, gold and mixed media.

Via Casual In Istanbul.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

After complaining a couple of days ago about the difficulty of seeing works of abstract cinema, it turns out that a collection of Oskar Fischinger’s great animations appeared earlier this year.

Decades before computer graphics, before music videos, even before Fantasia (the 1940 version), there were the abstract animated films of Oskar Fischinger (1900–1967), master of “absolute” or nonobjective filmmaking. He was cinema’s Kandinsky, an animator who, beginning in the 1920’s in Germany, created exquisite “visual music” using geometric patterns and shapes choreographed tightly to classical music and jazz. (John Canemaker, New York Times)

Oskar Fischinger is one of the greatest artists of the 20th century, embracing the abstraction that became the major art movement of that century, and exploring the new technology of the cinema to open abstract painting into a new Visual Music that performs in liquid time. (Biographer William Moritz)

We now understand Oskar Fischinger not only as a link between the geometric painting of pre-war Europe and post-war California but as a grandfather of the digital arts.

(Art Critic Peter Frank)

That’s good, so now how about the Whitneys, Jordan Belson, Harry Smith…?

Via Boing Boing.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The abstract cinema archive

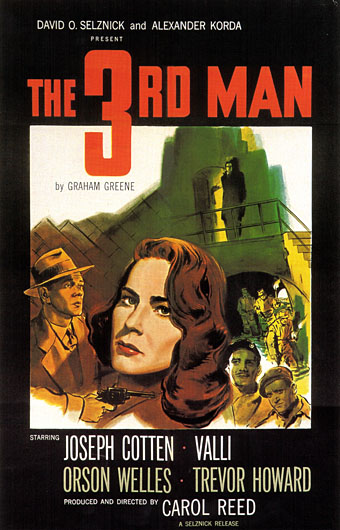

Three pages of them, and BIG scans as well, which makes a nice change for a web gallery. Strictly speaking, many of these films aren’t what’s usually classed as film noir (a debatable term at the best of times) but we shouldn’t quibble, painted posters are now a lost art.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Alida Valli, 1921–2006

Andreas Martens, artist of Rork.

A native of Germany, Andreas (Andreas Martens (1951- ) studied at the St. Luc comics school in Belgium, assisting Eddy Paape on Udolfo, before relocating to France. His genre series include Arq, Cromwell Stone, Cyrrus, Rork and its spin-off, Capricorne, as well as a number of single works such as La Caverne du Souvenir (The Cave of Memory), Coutoo, Dérives (Adrift), Aztèques, and Révélations Posthumes (Posthumous Revelations).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Harry Clarke, 1889–1931

Regular readers may have noticed the coming and going of certain features here recently, due to my experimenting with different plugins. One of the great features of the WordPress blogging software is its open source quality which allows anyone to write a plugin to extend the application. Ones I’ve been playing with over the past week are Justin Watt’s Random Image plugin which is creating the “Previously” “From the archives” images in the sidebar and the Social Bookmarks plugin which adds a “Bookmark this” feature to the end of posts. The latter I’ve disabled for now since it refuses to allow me to choose which bookmark selections are shown (del.icio.us and digg, for example), presenting instead a fruit salad of different gifs that looks messy. I may return this later if I can find a way to get it to work properly—PHP is not my forte—or find another plugin that does the required job.