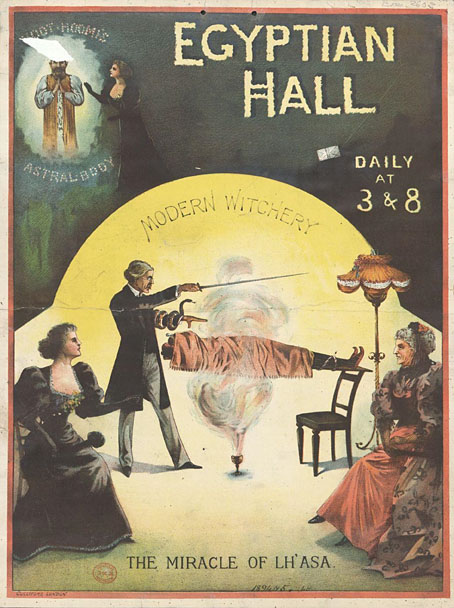

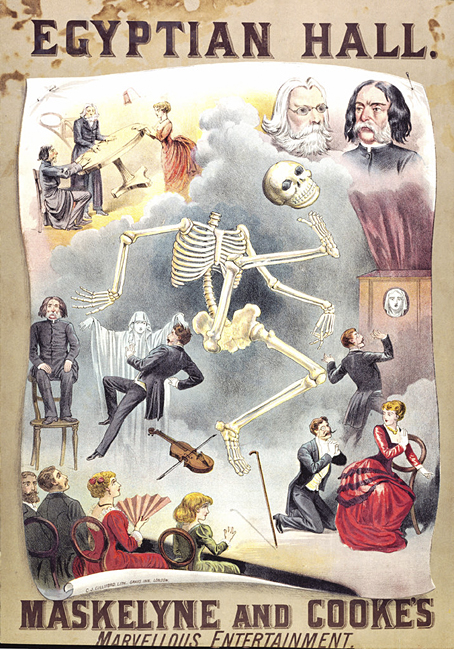

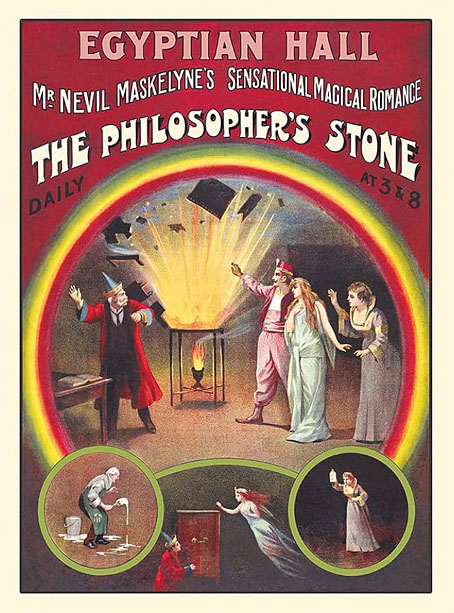

The Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly, circa 1896.

The Egyptian Hall, the front of which forms one of the most noticeable features on the southern side of Piccadilly, nearly opposite to Bond Street, was erected in the year 1812, from the designs of Mr. G. F. Robinson, at a cost of £16,000, for a museum of natural history, the objects of which were in part collected by William Bullock, F.L.S., during his thirty years’ travel in Central America. The edifice was so named from its being in the Egyptian style of architecture and ornament, the inclined pilasters and sides being covered with hieroglyphics; and the hall is now used principally for popular entertainments, lectures, and exhibitions. Bullock’s Museum was at one time one of the most popular exhibitions in the metropolis. It comprised curiosities from the South Sea, Africa, and North and South America; works of art; armoury, and the travelling carriage of Bonaparte. The collection, which was made up to a very great extent out of the Lichfield Museum and that of Sir Ashton Lever, was sold off by auction, and dispersed in lots, in 1819.

Here, in 1825, was exhibited a curious phenomenon, known as “the Living Skeleton,” or ‘the Anatomic Vivante,” of whom a short account will be found in Hone’s “Every-Day Book.” His name was Claude Amboise Seurat, and he was born in Champagne, in April, 1798. His height was 5 feet 7½ inches, and as he consisted literally of nothing but skin and bone, he weighed only 77¾ Ibs. He (or another living skeleton) was shown subsequently—in 1830, we believe—at “ Bartlemy Fair,” but died shortly afterwards. There is extant a portrait of M. Seurat, published by John Williams, of 13, Paternoster Row, which quite enables us to identify in him the perfect French native.

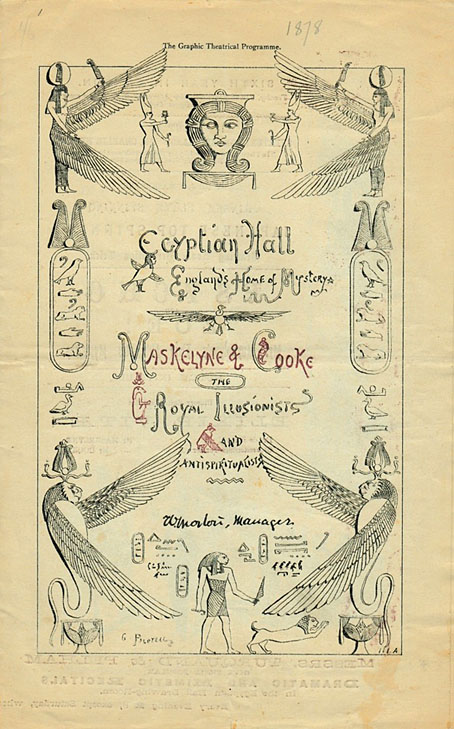

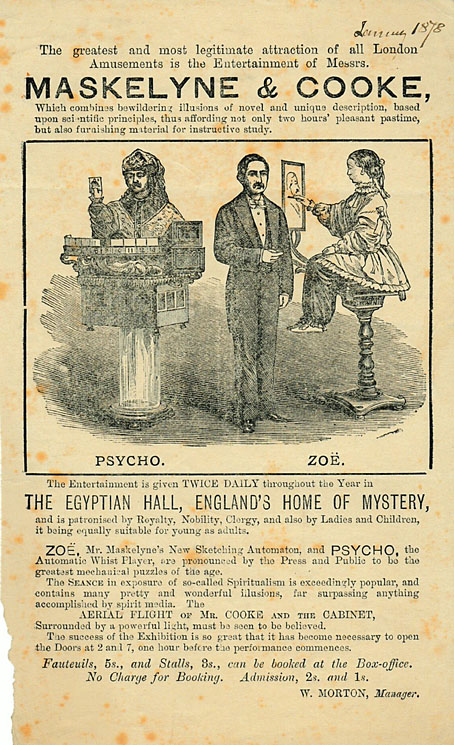

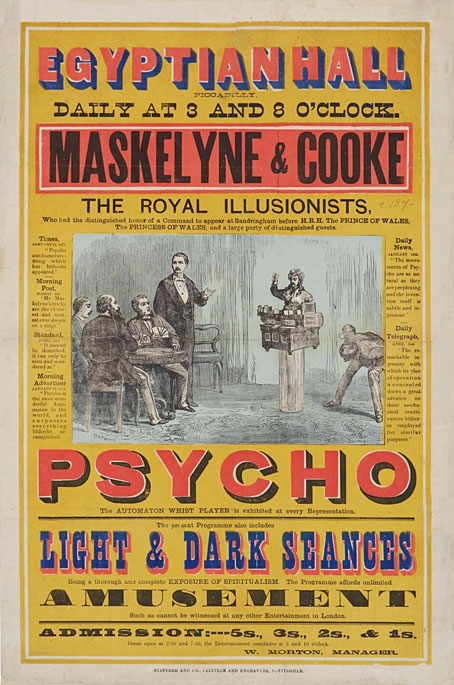

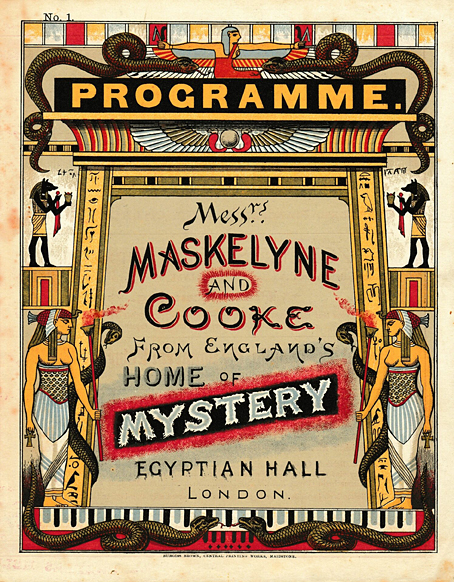

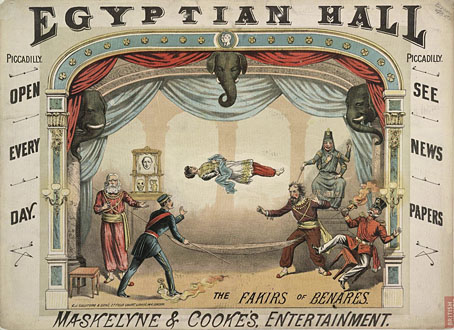

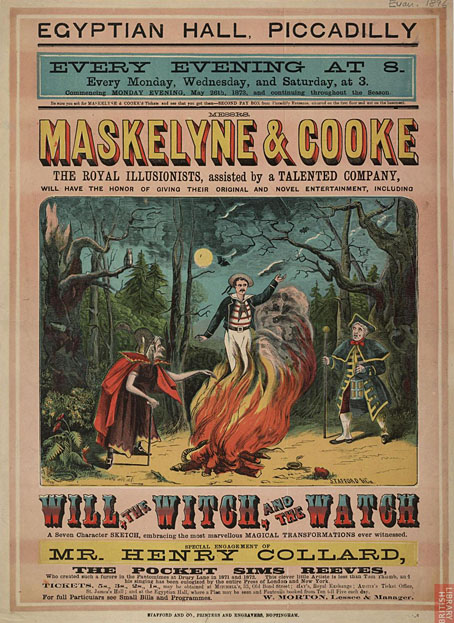

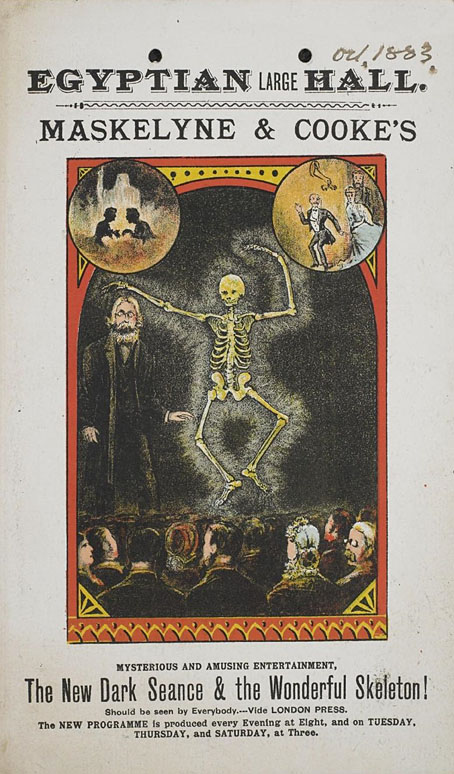

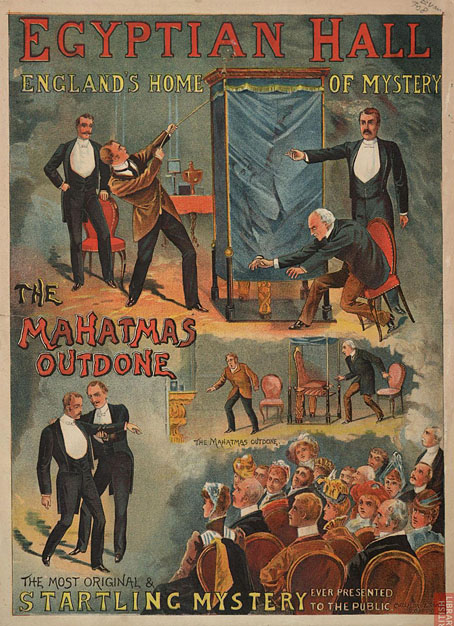

Of the various entertainments and exhibitions that have found a home here, it would, perhaps, be needless to attempt to give a complete catalogue; but we may, at least, mention a few of the most successful. In 1829, the Siamese Twins made their first appearance here, and were described at the time as “two youths of eighteen, natives of Siam, united by a short band at the pit of the stomach—two perfect bodies, bound together by an inseparable link.” They died in America in the early part of the year 1874. The American dwarf, Charles S. Stratton, “Tom Thumb,” was exhibited here in 1844; and subsequently, Mr. Albert Smith gave the narrative of his ascent of Mont Blanc, his lecture being illustrated by some cleverly-painted dioramic views of the perils and sublimities of the Alpine regions. Latterly, the Egyptian Hall has been almost continually used for the exhibition of feats of legerdemain, the most successful of these—if one may judge from the “run” which the entertainment has enjoyed—being the extraordinary performances of Messrs. Maskelyne and Cooke.

From Old and New London: A Narrative of its History, its People and its Places, Vol. 4 (1887) by Walter Thornbury

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Martinka & Co. catalogue, 1899

• Learned Pigs and other moveables of wonder

• Magicians

• Hodgson versus Houdini