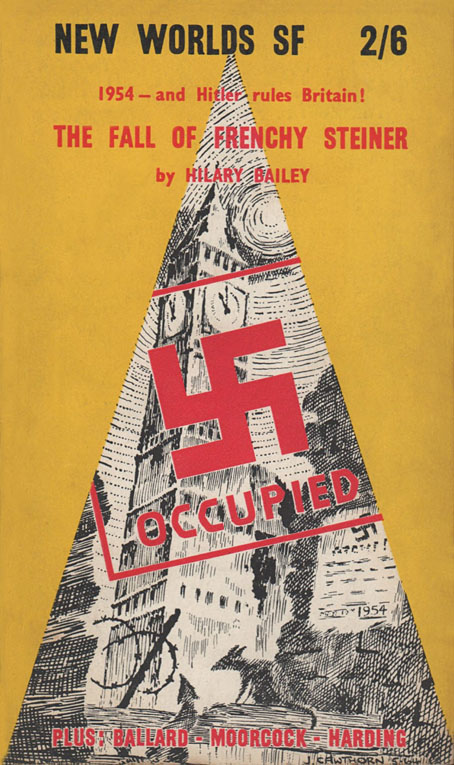

Art by James Cawthorn.

We know that Hitler placed a lot of faith in clairvoyants and astrologers, and this helped him lose the war. But what if there had been just one person with a genuine psi-talent. Could history have turned out like this…?

ONE

1954 WAS NOT a year of progress. A week before Christmas I walked into the bar of the Merrie Englande in Leicester Square, my guitar in its case, my hat in my hand. Two constables were sitting on wooden stools at the counter. Their helmets turned together as I walked in. The place was badly lit by candles, hiding the rundown look but not the run-down smell of home-brew and damp rot.

“Who’s he?” said one of the PCs as I moved past.

“I work here,” I said. Tired old dialogue for tired old people.

He grunted and sipped his drink. I didn’t look at the barman: I didn’t look at the cops. I just went into the room behind the bar and took off my coat. I went to the wash-basin, turned the taps. Nothing happened. I got my guitar out of its case, tested it, tuned it and went back into the bar with it.

“Water’s off again,” said Jon, the barman. He was a flimsy whisp in black with a thin white face. “Nothing’s working today…”

“Well, we’ve still got an efficient police force,” I said. The cops turned to look at me again. I didn’t care. I felt I could afford a little relaxation. One of them chewed the strap of his helmet and frowned. The other smiled.

“You work here do you, sir? How much does the boss pay you?” He continued to smile, speaking softly and politely. I sneered.

“Him?” I pointed with my thumb up to where the boss lived.” He wouldn’t, even if it was legal.” Then I began to worry. I’m like that—moody. “What are you doing here, anyway, officer?”

“Making enquiries, sir,” said the frowning one.

“About a customer,” said Jon. He leant back against an empty shelf, his arms folded.

“That’s right,” said the smiling one.

“Who?”

The cops’ eyes shifted.

“Frenchy,” said Jon.

“So Frenchy’s in trouble. It couldn’t be something she’s done. Someone she knows?”

The cops turned back to the bar. The frowning one said:”Two more. Does he know her?”

“As much as I do,” said Jon, pouring out the potheen. The white, cloudy stuff filled the tumblers to the brim. Jon must be worried to pour such heavy ones for nothing.

I got up on to the platform where I sang, flicking the mike which I knew would be dead as it had been since the middle of the war. I leaned my guitar against the dryest part of the wall and struck a match. I lit the two candles in their wall-holders. They didn’t exactly fill the corner with a blaze of light, they smoked and guttered and stank and cast shadows. I wondered briefly who had supplied the fat. They weren’t much good as heating either. It was almost as cold inside as out. I dusted off my stool and sat down, picked up my guitar and struck a few chords. I hardly realised I was playing Frenchy’s Blues. It was one of those corny numbers that come easy to the fingers without you having to think about them.

Frenchy wasn’t French, she was a kraut and who liked krauts? I liked Frenchy, along with all the customers who came to hear her sing to my accompaniment. Frenchy didn’t work at the Merrie Englande, she just enjoyed singing. She didn’t keep boyfriends long or often, she preferred to sing, she said. Frenchy’s singing was like what she’d give to a boyfriend, but this way she gave it to everyone. I didn’t know why she was called Frenchy. Probably her full name was Franziska.

Frenchy’s Blues only appealed to the least sensitive members of our cordial clientele. I didn’t care for it. I’d tried to do something good for her, but as with most things I tried to do well, it hadn’t come off. I changed the tune. I was used to changing my tune. I played Summertime and then I played Stormy Weather.

The cops sipped their drinks and waited. Jon leant against the shelves, his narrow, black-clad body almost invisible in the shadow, only his thin face showing. We didn’t look at one another. We were both scared—not only for Frenchy, but for ourselves. The cops had a habit of subpoenoeing witnesses and forgetting to release them after the trial—particularly if they were healthy men who weren’t already working in industry or the police force. Though I didn’t have to fear this possibility as much as most, I was still worried.

During the evening I heard the dull sound of far-away bomb explosions, the drone of planes. That would be the English Luftwaffe doing exercises over the still-inhabited suburbs.

Customers came and most of them went after a drink and a squint at the constables.

Normally Frenchy came in between eight and nine, when she came. She didn’t come. As we closed up around midnight, the cops got off their stools. One unbuttoned his tunic pocket and took out a notebook and pencil. He wrote on the pad, tore off the sheet and left it on the bar.

“If she turns up, get in touch,” he said. “Merry Christmas, sir,” he nodded to me. They left.

I looked at the piece of paper. It was cheap, blotting paper stuff and one corner was already soaking up spilled potheen. In large capitals, the PC had printed: “Contact Det. Insp. Braun, N. Scot. Yd, Ph. WHI 1212, Ext. 615.”

“Braun?” I smiled and looked up at Jon. “Brown?”

“What’s in a name?” he said.

“At least it’s CID. What do you think it’s about, Jon?”

“You never can tell these days,” said Jon. “Goodnight, Lowry.”

“Night.” I went into the room behind the bar, packed my guitar and put on my coat. Jon came in to get his street clothes.

“What do they want her for?” I said. “It’s not political stuff, anyway. The Special Branch isn’t interested, it seems. What—?”

“Who knows?” said Jon brusquely. “Goodnight.”

“Night,” I said. I buttoned up my coat, pulled my gloves on and picked up the guitar case. I didn’t wait for Jon since he evidently wasn’t seeking the company and comfort of an old pal. The cops seemed to have worried him. I wondered what he was organising on the side. I decided to be less matey in future. For some time my motto had been simple—keep your nose clean.

I left the bar and entered the darkness of the square. It was empty. The iron railings and trees had gone during the war. Even the public lavatories were officially closed, though sometimes people slept in them. The tall buildings were stark against the night sky. I turned to my right and walked towards Piccadilly Circus, past the sagging hoardings that had been erected around bomb craters, treading on loose paving stones that rocked beneath my feet. Piccadilly Circus was as bare and empty as anywhere else. The steps were still in the centre, but the statue of Eros wasn’t there any more. Eros had flown from London towards the end of the war. I wish I’d had the same sense.

I crossed the circus and walked down Piccadilly itself, the wasteland of St. James’s Park on one side, the tall buildings, or hoardings where they had been, on the other. I walked in the middle of the road, as was the custom. The occasional car was less of a risk than the frequent cosh-merchant. My hotel was in Piccadilly, just before you got to Park Lane.

I heard a helicopter fly over as I reached the building and unlocked the door. I closed the door behind me, standing in a wide, cold foyer unlighted and silent. Outside the sound of the helicopter died and was replaced by the roar of about a dozen motor-bikes heading in the general direction of Buckingham Palace where Field Marshal Wilmot had his court. Wilmot wasn’t the most popular man in Britain, but his efficiency was much admired in certain quarters. I crossed the foyer to the broad staircase. It was marble, but uncarpeted. The bannister rocked beneath my hand as I climbed the stairs.

A man passed me on my way up. He was an old man. He wore a red dressing gown and carried a chamber pot as far away from him as his shaking hand could stand.

“Good morning, Mr. Pevensey,” I said.

“Good morning, Mr. Lowry,” he replied, embarrassed. He coughed, started to speak, coughed again. As I began on the third flight, I heard him wheeze something about the water being off again. The water was off most of the time. It was only news when it came on. The gas came on three times a day for half-an-hour a day—if you were lucky. The electricity was supposed to run all day if people used the suggested ration, but nobody did, so power failures were frequent.

I had an oil stove, but no oil. Oil was expensive and could be got only on the black market. Using the black market meant risking being shot, so I did without oil. I had a place I used as a kitchen, too. There was a bathroom along the corridor. One of the rooms I used had a balcony overlooking the street with a nice view of the weed-tangled park. I didn’t pay rent for these rooms. My brother paid it under the impression that I had no money. Vagrancy was a serious crime, though prevalent, and my brother didn’t want me to be arrested because it caused him trouble to get me out of jail or one of the transit camps in Hyde Park.

I unlocked my door, tried the light switch, got no joy. I struck a match and lit four candles stuck in a candelabra on the heavy mantelpiece. I glanced in the mirror and didn’t like the dull-eyed face I saw there. I was reckless. My next candle allowance was a month off but I’d always liked living dangerously. In a small way.

I put on my tattered tweed overcoat, Burberry’s 1938, lay down on the dirty bed and put my hands behind my head. I brooded. I wasn’t tired, but I didn’t feel very well. How could I, on my rations?

I went back to thinking about Frenchy’s trouble. It was better than thinking about trouble in general. She must be involved in something, although she never looked as if she had the energy to take off her slouch hat, let alone get mixed up in anything illegal. Still, since the krauts had taken over in 1946 it wasn’t hard to do something illegal. As we used to say, if it wasn’t forbidden, it was compulsory. Even strays and vagabonds like me were straying under license—in my case procured by brother Gottfried, né Godfrey, now Deputy Minister of Public Security. How he’d made it baffled me, with our background, because obviously the first people the krauts had cleared out when they came to liberate us was the revolutionary element. And in England, of course, that wasn’t the tattered, hungry mob rising in fury after centuries of oppression. It was the well-heeled, well-meaning law-civil-service-church-and-medicine brigade who came out of their warm houses to stir it all up.

Anyway, thinking about Godfrey always made my flesh creep, so I pulled my mind back to Frenchy. She was a tall, skinny rake of a girl, a worn out, battered old twenty in a dirty white mac and a shapeless pull-down hat with the smell of a Cagney gangster film about it. I never noticed what was under the mac—she never took it off. Once or twice she’d gone mad and undone it. I had the impression that underneath she was wearing a dirty black mac. No stockings, muddy legs, shoes worn down to stubs, not exactly Ginger Rogers on the town with Fred Astaire. Still, the customers liked her singing, particularly her deadpan rendering of Deutschland Uber Alles, slow, husky and meaningful, with her white face staring out over the people at the bar. A kraut by nationality, but not by nature, that was Frenchy.

I yawned. Not much to do but go to sleep and try for that erotic dream where I was sinking my fork into a plate of steak and kidney pudding. Or perhaps, if I couldn’t get to sleep, I’d try a nice stroll round the crater where St. Pauls had been—my favourite way of turning my usual depression into a really fruity attack of melancholia.

Then there was a knock.

I went rigid.

Late night callers were usually cops. In a flash I saw my face with blood streaming from the mouth and a lot of black bruises. Then the knock came again. I relaxed. Cops never knocked twice—just a formal rap and then in and all over you.

The door opened and Frenchy stepped in. She closed the door behind her.

I was off the bed in a hurry.

I shook my head. “Sorry, Frenchy. It’s no go.”

She didn’t move. She stared at me out of her dark blue eyes. The shadows underneath looked as though someone had put inky thumbs under them.

“Look, French,” I said. “I’ve told you there’s nothing doing.” She ought to have gone before. It was the code. If someone wanted by the cops asked for help you had the right to tell them to go. No one thought any the worse of you. If you were a breadwinner it was expected.

She went on standing there. I took her by the shoulders, about faced her, wrenched the door open with one hand and ran her out on to the landing.

She turned to look at me. “I only came to borrow a fag,” she said sadly, like a kid wrongfully accused of drawing on the wallpaper.

The code said I had to warn her, so I shoved her back into my room again.

She sat on my rumpled bed in the guttering candlelight with her beautiful, mud-streaked legs dangling over the side. I passed her a cigarette and lit it.

“There were two cops in the Merrie asking about you,” I said. “CID!”

“Oh,” she said blankly. “I wonder why? I haven’t done anything.”

“Passing on coupons, trying to buy things with money, leaving London without a pass—” I suggested. Oh, how I wanted to get her off the premises.

“No. I haven’t done anything. Anyhow, they must know I’ve got a full passport.”

I gaped at her. I knew she was a kraut—but why should she have a full passport? Owning one of those was like being invisible—people ignored what you did. You could take what you wanted from who you wanted. You could, if you felt like it, turn a dying old lady out of a hospital wagon so you could have a joy-ride, pinch food—anything. A sensible man who saw a full passport holder coming towards him turned round and ran like hell in the other direction. He could shoot you and never be called to account. But how Frenchy had come by one beat me.

”You’re not in the government,” I said. “How is it you’ve got an FP?”

“My father’s Willi Steiner.”

I looked at her horrible hat, her draggled blonde hair, her filthy mac and scuffed shoes. My mouth tightened.

“You don’t say?”

“My father’s the Mayor of Berlin,” she said flatly. “There are eight of us and mother’s dead so no one cares much. But of course we’ve all got full passports.”

“Well, what the hell are you shambling around starving in London for?”

“I don’t know.”

Suspicious, I said: “Let’s have a look at it, then.”

She opened her raincoat and reached down into whatever it was she had on underneath. She produced the passport. I knew what they looked like because brother Godfrey was a proud owner. They were unforgable. Frenchy had one.

I sat down on the floor, feeling expansive. If Frenchy had an FP I was safer than I’d ever been. An FP reflected its warm light over everybody near it. I reached under the mattress and pulled out a packet of Woodies. There were two left.

French grinned, accepting the fag. “I ought to flash it about more often.”

We smoked gratefully. The allowance was ten a month. As stated, the penalty for buying on the black market, presuming you could get hold of some money, was shooting. For the seller it was something worse. No one knew what, but they hung the bodies up from time to time and you got some idea of the end result.

“About this police business,” I said.

“You don’t mind if I kip here tonight,” she said. “I’m beat.”

“I don’t mind,” I said. “Want to hop in now? We can talk in bed.”

She took off the mac, kicked away her shoes and hopped in.

I took off my trousers, shoes and socks, pulled down my sweater and blew out the candles. I got into bed. There was nothing more to it than that. Those days you either did or you didn’t. Most didn’t. What with the long hours, short rations and general struggle to keep half clean and slightly below par, few people had the will for sex. Also sex meant kids and the kids mostly died, so that took all the joy out of it. Also I’ve got the impression us English don’t breed in captivity. The Welsh and Irish did, but then they’ve been doing it for hundreds of years. The Highlanders didn’t produce either. Increasing the population was something people like Godfrey worried about in the odd moments when they weren’t eliminating it, but a declining birthrate is something you can’t legislate about. What with the slave labour in the factories, cops round every corner, the jolly lads of the British Wehrmacht in every street, and being paid out in food and clothing coupons so you wouldn’t do anything rash with the cash, like buying a razor blade and cutting your throat, you couldn’t blame people for losing interest in propagating themselves. There’d been a resistance movement up until three or four years before, but they’d made a mistake and taken to the classic methods—blowing up bridges, the few operating railway lines and what factories had started up. It wasn’t only the reprisals—on the current scale it was 20 men for every German killed, or 10 schoolkids or 5 women—but when people found out they were blowing up boot factories and stopping food trains a loyal population, as the krauts put it, stamped out the anti-social Judaeo-Bolshevik element in their midst.

The birthrate might have gone up if they’d raised the rations after that, but that might cause a population explosion in more ways than one.

Anyhow, it was warmer in there with Frenchy beside me.

“Would you mind,” I said, “removing your hat?”

I couldn’t see her, but I could tell she was smiling. She reached up and pulled the old hat off and threw it on the floor.

“What about these cops, then?” I asked.

“Oh—I really don’t know. Honestly, I haven’t done anything. I don’t even know anybody who’s doing anything.”

“Could they be after your full passport?”

“No. They never withdraw them. If they did the passports wouldn’t mean anything. People wouldn’t know if they were deferring to a man with a withdrawn passport. If you do something like spying for Russia, they just eliminate you. That gets rid of your FP automatically.”

“Maybe that’s why they’re after you…?”

“No. They don’t involve the police. It’s just a quick bullet.”

I couldn’t help feeling awed that Frenchy, who’d shared my last crusts, knew all this about the inner workings of the regime. I checked the thought instantly. Once you started being interested in them, or hating them or being emotionally involved with them in any way at all—they’d got you. It was something I’d sworn never to forget—only indifference was safe, indifference was the only weapon which kept you free, for what your freedom was worth. They say you get hardened to anything. Well, I’d had nearly ten years of it—disgusting, obscene cruelty carried out by stupid men who, from top to bottom, thought they were masters of the Earth—and I wasn’t hardened. That was why I cultivated indifference. And the Leader—Our Feuhrer—was no mad genius either. Mad and stupid. That was even worse. I couldn’t understand, then, how he’d managed to do what he’d done. Not then.

“I don’t know what it can be,” Frenchy was saying, “but I’ll know tomorrow when I wake up.”

”Why?”

“I’m like that,” she said roughly.

“Are you?” I was interested. ‘“Like—what?”

She buried her face in my shoulder. “Don’t talk about it, Lowry,” she said, coming as near to an appeal as a hard case like Frenchy could.

“OK,” I said. You soon learnt to steer away from the wrong topic. The way things, and people, were then.

So we went to sleep. When I woke, Frenchy was lying awake, staring up at the ceiling with a blank expression on her face. I wouldn’t have cared if she’d turned into a marmalade cat overnight. I felt hot and itchy after listening to her moans and mutters all night and I could feel a migraine coming on.

The moment I’d acknowledged the idea of a migraine, my gorge rose, I got up and stumbled along the peeling passageway. Once inside the lavatory I knew I shouldn’t have gone there. I was going to vomit in the bowl. The water was off. It was too late. I vomited, vomited and vomited. At least this one time the water came on at the right moment and the lavatory flushed.

I dragged myself back. I couldn’t see and the pain was terrible.

“Come back to bed,” Frenchy said.

“I can’t,” I said. I couldn’t do anything.

“Come on.”

I sat on the edge of the bed and lowered myself down. Go away, Frenchy, I said to myself, go away.

But her hands were on that spot, just above my left temple where the pain came from. She crooned and rubbed and to the sound of her crooning I fell asleep.

I woke about a quarter of an hour later and the pain had gone. Frenchy, mac, hat and shoes on, was sitting in my old arm chair, with the begrimed upholstery and shedding springs.

“Thanks, Frenchy,” I mumbled. “You’re a healer.”

“Yeah,” she said discouragingly.

“Do you often?”

“Not now,” she said. “I used to. I just thought I’d like to help.”

“Well, thanks,” I said. “Stick around.”

“Oh, I’m off now.”

“OK. See you tonight, perhaps.”

“No. I’m getting out of London. Coming with me?”

“Where. What for?”

“I don’t know. I know the cops want me but I don’t know why. I just know if I keep away from them for a month or two they won’t want me any more.”

“What the bloody hell are you talking about?”

“I said I’d know what it was about when I awoke. Well, I don’t—not really. But I do know the cops want me to do something, or tell them something. And I know there’s more to it than just the police. And I know that if I disappear for some time I won’t be useful any more. So I’m going on the run.”

“I suppose you’ll be all right with your FP. No problem. But why don’t you co-operate.”

“I don’t want to,” she said.

“Why run? With your FP they can’t touch you.”

“They can. I’m sure they can.”

I gave her a long look. I’d always known Frenchy was odd, by the old standards. But as things were now it was saner to be odd. Still, all this cryptic hide-and-seek, all this prescient stuff, made me wonder.

She stared back. “I’m not cracked. I know what I”m doing. I’ve got to keep away from the cops for a month or two because I don’t want to co-operate. Then it will be OK.”

“Do you mean you’ll be OK?”

“Don’t know. Either that or it’ll be too late to do what they want. Are you coming?”

“I might as well,” I said. When it came down to it, what had I got to lose? And Frenchy had an FP. We’d be millionaires. Or would we?

“How many FPs in Britain?” I asked.

“About two hundred.”

“You can’t use it then. If you go on the run using an FB you’d—we’d never go unnoticed, We’ll stick out like a searchlight on a moor. And no one will cover for us. Why should they help an FP holder with the cops after her?”

Frenchy frowned. “I’d better stock up here then. Then we can leave London and throw them off the scent.”

I nodded and got up and into the rest of my gear. “I’ll nip out and spend a few clothing coupons on decent clothes for you. You won’t be so memorable then. They’ll just think you’re some high-up civil servant. Then I’ll tell you who to go to. The cops will check with the dodgy suppliers last. They won’t expect FP holders to use Sid’s Foodmart when they could go to Fortnums. Then I’ll give you a list of what to get.”

“Thanks, boss,” she said. “So I was born yesterday.”

“If I’m coming with you I don’t want any slip-ups. If we’re caught you’ll risk an unpleasant little telling-off. And I’ll be in a camp before you can say Abie Goldberg.

“No,” she said bewilderedly. “I don’t think so.”

I groaned. “Frenchy, love. I don’t know whether you’re cracked, or Cassandra’s second cousin. But if you can’t be specific, let’s play it sensible. OK?”

“Mm,” she said.”

I hurried off to spend my clothing coupons at Arthur’s.

TWO

IT WAS A soft day, drizzling a bit. I walked through the park. It was like a wood, now. The grass was deep and growing across the paths. Bushes and saplings had sprung up. Someone had built a small compound out of barbed wire on the grass just below the Atheneum. A couple of grubby white goats grazed inside. They must belong to the cops. With rations at two loaves a week people would eat them raw if they could get at them. Look what had happened to the vicar of All Saints, Margaret Street. He shouldn’t have been so High Church—all that talk about the body and blood of Christ had set the congregation thinking along unorthodox lines.

I walked on in the drizzle. No one around. Nice fresh day. Nice to get out of London.

“Any food coupons?” said a voice in my ear.

I turned sharply. It was a young woman, so thin her shoulder blades and cheek bones seemed pointed. In her arms was a small baby. Its face was blue. Its violet-shadowed eyes were closed. It was dressed in a tattered blue jumper.

I shrugged. “Sorry, love. I’ve got a shilling—any use?”

“They’d asked me where I’d got it from. What’s the good?” she whispered, never taking her eyes off the child’s face.

“What’s wrong with the kid?”

“They’ve cut off the dried milk. Unless you can feed them yourself they starve—I’m hungry.”

I took out my diary. “Here’s the address of a woman called Jessie Wright. Her baby’s just died of diptheria. She may take the kid on for you.”

“Diptheria?” she said.

“Look, love, your kid’s half-dead anyway. It’s worth trying.”

“Thanks,” she said. Tears started to run down her face. She took the piece of paper and walked off.

“Hey ho,” said I, walking on.

I crossed the Mall and got the usual suspicious stares from the mixed assortment of soldiery that half-filled it. The uniforms were all the same. You couldn’t tell the noble Tommy from the fiendish Hun. I looked to my right and saw Buckingham Palace. From the mast flew a huge flag, a Union Jack with a bloody great swastika superimposed on it. I’d never got rid of my loathing for that symbol, conceived as part of their perverted, crazy mysticism. Field Marshal Wilmot had been an officer in the Brigade of St. George—British fascists who had fought with Hitler almost from the start. A shrewd character that Wilmot. He had a little moustache that was identical with the Leader’s—but as he was prematurely bald, hadn’t been able to cultivate the lock of hair to go with it. He was fat and bloated with drink and probably drugs. He depended entirely on the Leader. If he hadn’t been there it might have been a different story.

I walked down Buckingham Gate and turned right into Victoria Street. The Army and Navy Stores had become exactly what it said—only the military elite could shop there.

Arthur was in business in the former foreign exchange kiosk at Victoria Station. I bunged over the coupons. Sunlight streamed through the shattered canopy of the station. There had been some street fighting around here but it hadn’t lasted long.

“I want a lady’s coat, hat and shoes. Are these enough?”

Arthur was small and shrewd. He only had one arm. He put the coupons under his scanner. “They’re not fakes.” I said impatiently. “Are they enough?”

“Just about, mate—as it’s you,” he said. He was a thin-faced cockney from the City. His kind had survived plagues, sweatshops and the depression. He’d survive this, too. I happened to know he’d been one of Mosely’s fascists before the War—in fact he’d kicked a thin-skulled Jew in the head in Dalston in 1938, thus saving him from the gas chambers in 1948. Funny how things work out.

But somehow since the virile lads of the Wehrmacht had marched in he seemed to have cooled off the old blood brotherhood of the Aryans, so I never held it against him. Anyway, being about five foot two and weaselly with it, he was no snip for the selective breeding camps.

“What size d’you want?” he asked.

“Oh, God. I don’t know.’

“The lady should have come herself.” He looked suspicious.

“Coppers tore her clothes off,” I said. That satisfied him. A cop passed across the station at a distance. Arthur’s eyes flicked, then came back to me.

“Funny the way they left them in their helmets and so on,” he said. “Seems wrong, dunnit?”

“They wanted you to think they were the same blokes who used to tell you the time and find old Rover for you when he got lost.”

“Aren’t they?” Arthur said sardonically. “You should have lived round where I lived mate. Still, this won’t buy baby a new pair of boots. What’s the lady look like?”

“About five nine or ten. Big feet.”

“Coo—no wonder the coppers fancied her,” he jeered jealously. “You must feel all warm and safe with her. Thin or fat?”

“Come off it Arthur. Who’s fat?”

“Girls who know cops.”

“This one didn’t until last night.”

“Nothing dodgy is it?” His eyes started looking suspicious again.

Trading licenses were hard to come by these days. I thought of telling him about Frenchy’s full passport, but dismissed the idea. It would sound like a fantastic, dirty great lie.

“She’s OK. She just wants some clothes that’s all.”

“If she got her clothes torn off why don’t she want a dress? That’s more important to a lady than a hat—a lady what is a lady that is.”

“Give me the coupons, Arthur.” I stretched out my hand.”You’re not the only clothes trader around. I came here to buy some gear, not tell you my love life.”

“OK, Lowry. One coat, one hat, one pair of shoes, size 7—and God help you if her feet’s size 5.” Arthur produced the things with a wonderful turn of speed. “And that’ll be a quid on top.”

I’d expected this. I handed him the pound. As I put the goods in a paper bag I said “I took the number of that quid, mate. If the cops call on me about this deal I’ll be able to tell them you’re taking cash off the customers. They may not nick you, of course—but they may soak you hard.”

He called me a bastard and added some more specific details, then said”No hard feelings, Lowry. But I thought all along this was a dodgy deal.”

“You mind your business, chum, I’ll mind mine,” I said. “So long.”

“So long,” he said. I headed back towards the park.

Frenchy was asleep when I got back. She looked fragile, practically TB. I woke her up and handed her the gear. She put it on.

“Frenchy, love,” I said sadly. “I’ve got to break it to you—you must have a wash. And comb your hair. And haven’t you got a lipstick?”

She sulked but I fetched some water. By some accident Pevensey had missed what was left in the taps. She washed, combed her hair with my comb and we made up her lips with a Swan Vesta.

I stood back. Black coat, a bit short with a fur collar, white beret and black high heeled shoes.

“Honestly, French, you look like Marlene Dietrich,” I said partly to give her the morale to carry off the FP-ing, partly because it was almost true. It was a pity she looked so undernourished, but perhaps they’d think it was natural.

“Get yourself some make-up while you’re at it.”

“Here,” she said in alarm, “I don’t know what to do.”

“You mean you’ve never used that passport,” I said.

“You wouldn’t if you were me,” she replied. For her that was obviously the question you never asked, like”where were you in ’45” or”what happened to cousin Fred.” Her face was dark.

I passed it off. “You’re cracked. Never mind. Just march into the place. Look confident. Tell them what you want. They’ll cotton on immediately. You probably won’t even need to show it to them. Scoop the stuff up and go. Don’t forget they’re scared of you.”

“OK.”

“Here’s the list of what we want and where to get it.”

“Yeah,” she glanced over the list. “Brandy, eh?”

I grinned. ‘‘Christmas, after all. You never drink, though.”

“No. It does something bad to me.”

“Uh huh. Use a slight German accent. That’ll convince them.”

She left and I went and lay down. I felt tired after all that.

And, lo, another knock at my door. Thinking it was Pevensey wanting me to get him some more quack medicine, I shouted “come in.”

*

He stood in the doorway, a vision of loveliness in his black striped coat and pinstriped trousers. He glanced round fastidiously at my cracked lino, peeling wallpaper, the net curtain that was hanging down on one side of the small greasy window. Well, he had a right. He paid the rent, after all.

I didn’t get up. “Hullo, mein Gottfried,” I said.

“Hullo, old man.” He came in. Sat down on my armchair like a man performing an emergency appendectomy with a rusty razor blade. He lit a Sobranie.

As an afterthought he flung the packet to me. I took one, lit it and shoved the packet under the mattress.

“I thought I’d look in,” he said.

“How sweet of you. It must be two years now. Still, Christmas is the time for the family, isn’t it?”

“Well, quite… How are you?”

“Rubbing along, thanks, Godfrey. And you?”

“Not too bad.”

The scene galled me. When we were young, before the war, we had been friends. Even if we hadn’t been, brothers were still brothers. It wasn’t that I minded hating my brother, that’s common enough. It was that I didn’t hate him the way brothers hate. I hated him coldly and sickly.

At that moment I would have liked to fall on him and throttle him, but only in the cold, satisfied way you rake down a flypaper studded with flies.

Besides I still couldn’t see why he had come.

“How’s the—playing?” he asked.

“Not bad, you know. I’m at the Merrie Englande these days.”

“So I heard.”

Hullo, I thought, I see glimmers of light. He saw I saw them—he was, after all, my brother.

“I wondered if you’d like some lunch,” he said.

Normally I would have refused, but I knew he might stay and catch Frenchy coming back. So I pretended to hesitate. “All right, I’m hungry enough for anything.”

We went down the cracked steps and walked up Park Lane. The drizzle had stopped and a cold sun had come out and made the street look even more depressing. Boarded up hotels, looted shops, cracked facades, grass growing in the broken streets, bent lamp standards, the park itself a tangled forest of weeds. It was sordid.

“Thinking of cleaning up, ever, Godfrey?” I asked.

“Not my department,” he said.

”Someone ought to.”

“No man-power, You see,” he said. I bet, I thought. Naturally they left it. One look was enough to break anyone’s morale. If you were wondering how defeated and broken you were and looked at Park Lane, or Piccadilly, or Trafalgar Square, you’d soon know—completely.

Godfrey took me to a sandwich and soup place on the corner. A glance and the man behind the counter knew him for an FP holder. So the food wasn’t bad, although Godfrey picked at it like a man used to something better.

Conversation stopped. The customers bent their shoulders over their plates of sandwiches and munched stolidly. Godfrey didn’t seem to notice. He probably never had noticed. I had to face facts—although a member of my own family, Godfrey had always been a kraut psychologically. Always neat, always methodical, jumping his hurdles—exams, tests and assignments at work—like a trained horse. It wasn’t that he didn’t care about other people—I can’t say I did—he just never knew there was anything to care about.

“How’s the department?” I asked, beginning the ridiculous question and answer game again—as if either of us worried about anything to do with the other.

”Going well.”

“And Andrea?”

“She’s well.”

She ought to be, I thought. Fat cow. She’d married Godfrey for his steady civil service job and made a far better bargain that she’d thought.

“What about you—are you thinking of getting married?”

I stared at him. Who married these days unless they had a steady job at one of the factories or on road transport, or, of course, in the police?

“Not exactly. Haven’t really got the means to keep my bride in the accustomed manner.”

“Oh,” said Godfrey. Watch it, I thought. I knew that expression. “Oh, they said Sebastian’d been riding Celeste’s bike, mother.” “Oh, father, I thought you’d given Seb permission to go out climbing.”

“I mentioned it because they told me you were engaged to a singer at the Merrie Englande.”

“Who are they?”

“Well, my private secretary, as a matter of fact. He’s a customer.”

Yeah, I thought, like a rag and bone man’s a customer at the Ritz. He’d heard it from some spy.

“Well,” I said. “I can’t think how he managed to get that idea. I’m not sure there’s a regular singer at the Merrie…”

“This girl was supposed to be like you—a sort of casual entertainer. A German girl I think he said.”

Too specific, chum. That line might just work with a stranger—not with your little brother.

“I think I’ve met her. In fact I’ve played for her once or twice. I don’t know much about her, though. I’m certainly not engaged to her.”

Godfrey bit into a sandwich. I’d closed that line of enquiry. He was wondering how to open another.

“That’s a relief. She sounds a tramp.”

“Maybe.”

“We want to repatriate her—know where she is?”

“Why should I?” I said. “Apart from that, why should I help you? If she doesn’t want to be repatriated, that’s her business.”

“Be realistic, Sebby—anyway, she does want to be, or she would do, if she knew. Her aunt’s died and left her a lot of money. The other side has asked us to let her know so she can go home and sort out her affairs.”

I went on drinking soup, but I wondered. Perhaps the story was true. Still, I didn’t need to put Godfrey on to her—I could tell her myself.

“Well, I’ll tell her if I see her. I doubt if I shall. I should leave a message at the Merrie.”

“Yes.”

He looked up broodingly, staring round in that blank way people have when they’re bored with their eating companion.

I followed his gaze. My eyes lit on Frenchy. Loaded with parcels, she was buying food and having a flask filled with coffee at the counter. I went rigid. Frenchy had gained confidence—she was buying like an FP holder. And anyone with that amount of stuff on them attracted attention anyway. She was attracting it all right. Godfrey was the only man in the room who wasn’t looking at her and pretending not to. He was just looking at her. I couldn’t decide if he was watching her like a cat or just watching.

“Heard about Freddy Gore,” I said.

“No,” said Godfrey, not taking his eyes off her.

“He committed suicide,” I said.

“Well I’m damned,” said Godfrey, looking at me greedily. “Why?”

“It was his wife. He came home one afternoon. I spoke on hastily. Frenchy was still buying. Half the customers were still pointedly ignoring her—apart from anything else she looked quite good in her new gear. She picked up her stuff and left without showing her FP to the man behind the counter. She left without Godfrey noticing. I brought my tale of lust, adultery, rape and murder in the Gore family to a speedy close. A horrible thought had struck me. Godfrey was a high up. He knew about Frenchy and he knew I knew her. There were a lot of cops on the job and he might have fixed it so that some were watching my house. Somehow I had to shift him and catch Frenchy before she got back.

“Shocking story,” said Godfrey. looking at his watch. “I must be getting back. Like a lift?”

“Not going in that direction,” I said. “Thanks all the same.”

So he flagged down a passing car and told the sulky driver to take him to Buckingham Palace—the krauts had restored it at huge expense for the Ministry of Security as well as our paternal governor.

I walked slowly down the road, turned off and ran like hell. I caught Frenchy, all burdened with parcels, just in time.

“Better not go back,” I gasped. “They may be watching the hotel.”

There was a car standing outside a house just down the street. I ran her up to it and tugged at the door. It wasn’t locked. I shoved her paper bags, flask and all, in and got in the driving seat.

A stocky man ran out of the house. He had a revolver in his hand. I started up. Frenchy had the passport out. I grabbed it and waved it at the man with the gun.

“Full passport!” I yelled.

He stood staring at the back of the car. He didn’t even dare snarl.

“What makes you think they’re watching the hotel?” she asked.

I told her about Godfrey.

She frowned. “I must be right about having to run.”

“Are you sure it isn’t this legacy they say you’ve inherited?”

“I’ve only got one aunt and she’s broke. Besides, why should your brother get involved in such a silly little business?”

“Because your father’s so important. Or perhaps Papa just wants you home and made up the aunt business to cover up the fact that you’re his no-good daughter who’s dragging about occupied territory, dragging the family name in the mud behind her.”

“Could be. It’s not though. I’m still not sure—you’ll have to believe me. In the past I’ve been—well—important. It’s to do with that, I know.”

“What sort of important?”

She began to cry, great, racking sobs which bent her double.

“Don’t ask me—oh, don’t ask me.”

I got hard-hearted. “Come on, Frenchy. Why should I break the law for you?”

”I don’t want to remember—I can’t remember,” she gasped.

“Nuts. You can remember if you want to.”

“I can’t. I don’t want to.”

I passed her my handkerchief silently. How important could she have been—at 20 years old? She must have been at school until a couple of years ago.

“Where did you go to school?” I asked, more to pass the time than anything.

“I was at the Berlin Gymnasium for Girls. When I was 13, I—they took me away.”

”Then the tears stopped and when I glanced at her, she had fainted. I pushed her back so that she was sitting comfortably, and drove on.

As dark came we reached Histon, just outside Cambridge, and spent the night in the car, parked beside a hedge, inside a field.

When I woke next morning, there was a rifle barrel in my ear.

THREE

“Oh, GAWD,” I said. “What’s this?”

A hand opened the car door and dragged me out. I lay on the ground with the barrel pointing at my belly. Above the barrel was a red face topped by a trilby hat. It wasn’t a copper anyway.

I glanced sideways at the car. Inside, Frenchy was sitting up. Outside another man pointed a rifle at her temple, through the open window.

“What’s all this about?” I said.

“Who’re you?” the man said.

“Sebastian Lowry and Frenchy Steiner.”

“What’re you here for?”

“Just riding.”

The gun barrel dropped. The man was looking at his friend.

Then I saw—Frenchy had her passport out.

He touched his hat and retreated quickly, mumbling apologies. So I got back in the car and we snuggled up and back to sleep.

When we woke up, we had coffee from the flask, and a sandwich. Then we walked round the field. One or two birds cheeped from the bare hedges and our feet sank into ploughed furrows. It was silent and lonely. We walked round and round, breathing deeply.

We sat down and looked out over the big, flat field, sharing a bar of chocolate.

Frenchy smiled at me—a real smile, not her usual what-the-hell grin. I smiled back. We sat on. No noise, no people, no grimy, cracked buildings, no cops. A pale sun was high in the sky. The birds cheeped. I took Frenchy’s hand. It felt strange, to be holding someone’s hand again. It was warm and dry. Her fingers gripped mine. I stared at the pale, pointed profile beside me, and the long, messy blonde hair. Then I looked at the field again. We started a second bar of chocolate. Frenchy yawned. The silence went on and on. And on and on.

I was staring numbly across the acres of brown earth when Frenchy’s hand clenched painfully on mine.

Slowly, from behind every bush, like the characters in some monstrous, silent film, the cops were rising. On all sides, over the bare bushes, came a pair of blue shoulders, topped by a helmet. They rose slowly until they were standing. Then they moved silently forward. They tightened in.

Frenchy and I rose. The circle closed. To keep in the centre we had to move over to the road. Slowly they drove us out of the field, past our car, through the gate and on to the road. No one spoke. All we heard was the sound of their boots on the earth. Their faces were rigid, like cops faces always are.

Coming through the gate, we saw the reception committee. Three of them. My friend Inspector Braun, all knife-edged creases and polished buttons, and brother Godfrey. And then a short fat man I didn’t know. He was wearing a well-cut suit and power, as they say, was written all over him, from his small, neatly shod feet, to his balding head.

Frenchy stepped up to the group. “Hullo, father,” she said in German.

“Hullo, Franziska. We’ve found you at last, I see.”

Godfrey smirked. Extra rations for good old Gottfried tomorrow. Maybe the Iron Cross.

So I thought I’d embarrass him. “Hi, Godfrey, old man.”

“Morning, Sebastian.” How he wished I wasn’t shaking his hand. “We’re parked up the road. Come on.”

So we walked up the road to the shiny blue car that would take us back to God knew where—or what.

How silently they must have moved. What bloody fools we’d been not to get away after those two farmers had copped us. Godfrey and friends had probably had bulletins out for us all morning.

I sat at the back, between Godfrey and the Inspector. Frenchy was in front with her father and the driver.

“It’s nice to know officialdom has its more human side,” I remarked. “To think that deputy security minister, a CID Inspector and 50 coppers should all come out on a cold winter’s morning to see a young girl gets the legacy that’s rightfully hers.”

Godfrey said nothing. He merely looked important. From the way Braun didn’t grip my arm and the driver didn’t keep glancing over his shoulder to see who I was coshing, I got the impression this wasn’t a hanging charge. There was a sort of alligator grin in the air—cops taking home a naughty under-age couple who had run off to get married—not that cops did that kind of little social service job these days, but, wistfully, they kept trying to make you think so.

But what was the set-up? In front Frenchy had given up talking to her father—he cut every remark off at source. Why? No family rows in public? Frenchy, what I could see of her, looked like a girl on a cart bound for the scaffold. Her father looked like a man determined to knock some sense into his daughter’s flighty head as soon as he got her home. Godfrey merely looked pontifical. Braun looked official.

Frenchy tried again. “Father. I can’t go—”

“Be quiet!” said her father. Godfrey was listening hard. Suddenly I got the picture. Godfrey and Braun didn’t know what it was all about. And Frenchy’s father didn’t want them to.

It must be really something, then, I thought.

There was silence all the way back to London. What about me? I thought. I’m just not in this at all. But I bet it’s me who takes the rap. The car stopped in Trafalgar Square. Frenchy and her father got out. He hurried her up the steps of the Goering Hotel. Her eyes were burning like coals.

Then Godfrey and Braun pulled me out. “You’ll be in a suite here till we decide what to do with you,” Godfrey said in a low voice. “Don’t worry. I’ll do what I can to help.”

I won’t say tears came to his eyes—I knew just how far he would go to help. I said goodbye to him and Braun led me up the marble steps. The place was crowded with neat soldiery. We were joined by the hotel manager and two coppers. We went up to the top storey and I was shown my suite. Three rooms and a bathroom. Quite a nice little shack, although somewhat Teutonically furnished. It was elegant, but there was the smell of loot about it. You kept wondering which bit of furniture covered the bloodstains where they’d bayonetted the Countess and her kids one morning.

Then the two policemen stationed themselves, one at the door and one inside with me. That wasn’t so pleasant. I wondered when the cop was going to suggest a hand of nap to while away the time before the execution. I looked about appreciatively, sat down on the blue silk sofa and said “What now?”

A waiter came in with tea and toast. One cup. I asked the cop if he’d like some. He refused. As I went to pour out my second cup I saw why, because the room began to spin. “This hotel isn’t what it was,” I muttered and fell down.

*

I woke up next morning in a four-poster. Frenchy, in a red silk nightdress and negligee was bending over me with a cup of coffee. I hauled myself up, noticing my blue silk pyjamas, and took the cup.

She sat down at the Louise XIV table beside the bed. She went on eating rolls and butter. Her hair, obviously washed, cascaded down her back like gold thread.

“Very nice,” I said, handing back my cup for a refill. “If I didn’t wonder whose Christmas dinner I was being fattened for. Where’s the cop?”

“I sent him outside.” I began to glance round. The windows were barred.

“You can’t get out. The place is heavily guarded and the cops will shoot you on sight.”

“That’s new?”

She ignored me. “You’re quite safe as long as you’re with me. I’ve told them I’ve got to have you with me.”

“That’s nice. How long will you be around?”

“I thought you’d spot a snag!”

“Look, Frenchy. I think you’d better tell me what this is about. It’s my carcass after all.”

“I will,” she said calmly. “Prepare yourself for surprises.” She seemed very matter of fact, but her face had the calm of a woman who’s just had a baby, the pain and shock were over, but she knew this was really only the beginning of the trouble.

“I told you I was at a gymnasium in Berlin until I was 13. Then I began seeing visions. Of course, the tutors didn’t make much of it at first. It’s not too unusual in girls at the beginning of puberty. The trouble was, they weren’t the usual kind of visions. I used to see tables surrounded by German officers. I used to overhear conferences. I saw tanks going into battle, burning cities, concentration camps—things I couldn’t possibly know about. Then, one night, my room-mate heard me talking English in my sleep. I was talking about battle plans, using military terms and English slang I also couldn’t possibly have known. She told the House Leader. The House Leader told my father, who was then only a captain in the S.S. Father was an intelligent man. He took me to Karl Ossietz, one of the Leader’s chief soothsayers. A month later I was installed in a suite at headquarters. I was dressed in a white linen dress, my hair was bound with a gold band. I’d become part of the German myth…

“I was the virgin who prophesied to Atilla, I was thirteen years old and I lived like a ritual captive for four years, Officiating at sacrifices and Teutonic Saturnalia, watching goats have their throats cut with gold knives, seeing torch light on the walls—all that. And I thought it was marvellous, to be helping the cause like that. I went into a kind of mystic dream where I was an Ayran queen helping her nation to victory. And in my midnight conferences with the Leader I prophesied. I told him not to attack Russia—I knew he would be defeated. I told him where to concentrate his forces to use them to their best effect. Oh, and much, much more…

“Also only I could soothe him when his attacks of mania came on—by putting my hands on him the way I did for you the other day. I’m not a real healer. I can’t cure the body. But I can reach into overtaxed or unstable minds and take away the tightness.

“When the war ended, I just left in a daze. They thought they didn’t really need me at that time. There was something in the back of my mind—I don’t know what it was—made me come here, with my passport, my safe conducts, my letters of introduction… When I saw what I had done to you all—what could I do? I tried to kill myself and failed—maybe I wasn’t trying hard enough. Then I tried to live with you, simply because I couldn’t think of anything else to do. A stronger person might have thought of practical ways to help—but I’d spent four years in an atmosphere of blood and hysteria, calling on the psychic part of me and ignoring the rest. I was unfit for life. I just tried to forget everything that had ever happened to me.”

She shrugged. “That’s it.”

I stared at her, feeling a horrible pity. She knew she had been used to kill millions of people and reduce a dozen nations to slavery. And she had got to live with it.

“What’s it all about now?” I asked.

“They need me again. There must be desperate problems to be solved. Or the Leader’s madness is getting worse. Or both. That’s why I felt if I could disappear for a month it would be all right. By that time no one could have cleared up the mess.” She lit a cigarette, passed it to me and lit one for herself.

“What are you going to do?”

“I don’t know. If I don’t help they’ll torture me until I do. I’m not strong enough to resist. But I can’t, can’t can’t co-operate any more. If I had the guts I’d kill myself but I haven’t. Anyway, they’ve taken away anything I could use to do it. That’s why all the windows are barred—it’s not to stop you escaping. It’s to stop me from throwing myself out. I don’t suppose you’d kill me quickly, so I wouldn’t know anything about it?”

In a sense the idea was tempting. A chance to get back at the Leader with a vengeance. But I knew I couldn’t kill poor, thin Frenchy.

I told her so. “I’m too kind-hearted,” I said. “If I killed you, how could I go on hoping you’d have a better life?”

“I won’t. If I’m needed they’ll cage me again. And this time I’ll have known freedom. I’ll be back in robes, with incense and torchlight and all the time I’ll be able to remember being free—walking in the field at Histon, for example.” I felt very sad. Then I felt even sadder—I was thinking about myself.

“What happens next?” I said.

“They’ll fly me to Germany. You’re coming too.”

“Oh, no.” I said. “Not Germany. I wouldn’t stand a chance.”

“What chance do you stand here? If I went and you stayed, you’d be shot the moment I left the building. They can’t risk letting you go about with your story.”

Her shoulders were bowed. She looked as if she had no inner resources left. “I’m sorry. It’s my fault. I should have left you alone. If I’d never made you run away with me you’d be safe now.”

That wasn’t how I remembered it exactly, but I’d rather blame her than me for my predicament. I agreed, oh, how I agreed. Still, once a gent, always a gent. “Never mind that. I’ll come and perhaps we can think of something.” I was dubious about that, but by that time I was too far in.

So at eleven that morning we left the hotel for the airport. From Berlin we went by limousine to the Leader’s palace. I’ve never been so afraid in my life. It’s one thing to go in daily danger of being shot, or sent to starve in a camp. It’s another thing to fly straight into the centre of all the trouble. I was so afraid I could hardly speak. Not that anyone wanted to hear from me anyway. I was just a passenger—like a bullock on its way to the abattoir.

During the trip, Frenchy’s father kept up a nervous machine-gun monologue of demands that she would cooperate and promises of a glorious future for her. Frenchy said nothing. She looked drained.

We arrived in the green courtyard of the palace. On the other side of the wall I heard the rush of a water-fall into a pool. The palace was half old German mansion, half modern Teutonic, with vulgar marble statues all over the place—supermen on super-horses. That’s the nearest they’d got to the master-race, so far. A white haired old man led the jackbooted party which met us.

Frenchy smiled when she saw him, a child’s smile.

“Karl,” she said. Even her voice was like the voice of a very young girl. I shuddered. The spell was beginning to operate again—that blank face, the voice of the little school girl. Oh, Frenchy, love, I sighed to myself. Don’t let them do it to you. She was being led along by Karl Ossietz, across the green courtyard.

We made a peculiar gang. In front, Ossietz, tall and thin, with long white hair, and Frenchy, now looking so frail a breeze might blow her away. Behind them a group of begonged generals, all horribly familiar to me from seeing their portraits on pub signs. Just behind them rolled Frenchy’s father, trying to join in. Then me, with two ordinary German cops. I caught myself feeling peeved that if I made a dash for it I’d be shot down by an ordinary cop.

Then Karl turned sharply back, stared at me and said: “Who’s that?”

Her father said: “He’s an Englishman. She wouldn’t come without him.”

Karl looked furious and terrified. His face began to crumble. “Are you lovers?” he shouted at Frenchy.

“No, Karl,”’ she whispered. He stared long and deeply into her eyes, then nodded.

“They must be separated,” he said to Frenchy’s father.

Frenchy said nothing. Suddenly I felt more than concern for her—panic for myself. The only reason I’d come here was because she could protect me. Now she could, but she wasn’t interested any more. So instead of being shot in England, I was going to be shot right outside the Leader’s front door. Still, dead was dead, be it palace or dustbin.

We entered the huge dark hall, full of figures in ancient armours and dark horrible little doors: leading away to who knew where. The mosaic floor almost smelt of blood. My legs practically gave way under me. I saw Frenchy being led up the marble staircase. I felt tears come to my eyes—for her, for me, for both of us.

Then they took me along a corridor and up the back stairs, They shoved me through a door. I stood there for several minutes. Then I looked round. Well, it wasn’t a rat-haunted oubliette, at any rate. In fact it was the double of my suite at the Goering Hotel. Same thick carpets, heavy antique furniture, even—I poked my head round the door—the same four-poster. Obviously they picked up their furniture at all the little chateaux and castles they happened to run across on a Saturday morning march.

In the bedroom, torches burned. I took off my clothes and got into bed. I was asleep.

The first thing I saw as I awoke was that the torches were burning down. Then I saw Frenchy, naked as a peeled wand, pulling back the embroidered covers and coming into bed. Then I felt her warmth beside me.

“Do it for me,” she murmured. “Please.”

“What?”

“Take me,” she whispered.

“Eh?” I was somewhat shocked. People like Frenchy and me had a code. This wasn’t part of it.

“Oh please,” she said, pressing her long body against me. “It’s so important.”

“Oh—let’s have a fag,” I said.

She sank back. “Haven’t got any,” came her sulky voice.

I found some in my pocket and we lit up. “May as well drop the ash on the carpet,” I said. “Not much point in behaving nicely so we’ll be asked again.” I was purposely being irrelevant. Code or no code the situation was beginning to affect me. I tried to concentrate on my imminent death. It had the opposite effect.

“I don’t understand, love,” I said, taking her hand.

“I had to crawl over the roof to get here,” she said, rather annoyed.

“It can’t just be passion,” I suggested politely.

“Didn’t you hear—?”

“My God,” I said. “Ossietz. Do you mean that if you’re not a virgin, you can’t prophesy?”

“I don’t know—he seems to think so. It’s my only chance. He’ll make me do whatever he wants me to—but if I can’t perform, if it seems the power’s gone—it won’t matter. They may shoot me, but it will be a quick death.”

“Don’t be so dramatic, love.” I put my cigarette out on the bed head and took her in my arms. “I love you, Frenchy.” I said. And it was quite true. I did.

FOUR

THAT WAS THE best night of my life. Frenchy was sweet, and actually so was I. It was a relief to drop the mask for a few hours. As dawn came through the windows she lay in our tangled bed like a piece of pale wreckage.

She smiled at me and I smiled back. I gave her a kiss. “A man who would do anything for his country,” she grinned.

“How are you going to get back?” I said.

“I thought I’d go back over the roof—but now I’m not sure I’ll ever walk again.”

I said: “Have I hurt you?”

“Like hell. I’ll bluff my way out. The guards will be tired and I doubt if they know anything. Anyway all roads lead to the same destination now.”

I began to cry. That’s the thing about an armadillo—underneath his flesh is more tender than a bear’s. Not that I cared if I cried, or if she cried, or if the whole palace rang with sobs. The torches were guttering out.

She stood naked beside the bed. Then she put on her clothes, said goodbye. I heard her speaking authoritatively outside the door, heels clicking, and then her feet going along the corridor.

I just went on crying. Her meeting with the Leader was in two hours time. If I went on crying for two hours I wouldn’t have to think about it all.

I couldn’t. By the time the guard came in with my breakfast, I was dressed and dry-eyed. He looked through the open door at the bed and gave a wink. He said something in German I couldn’t understand, so I knew the words weren’t in the dictionary. I stared at the bed and my stomach lurched. It seemed a bit rude to feel lust for a woman who was going to die. Still I was going to die, too, so it was probably all right. Perhaps there was a heaven—but I doubted if being in bed with Frenchy was part of it. Perhaps they’d take pity on me and put me in the Moslem Section with Frenchy as my houri. I doubted if there was an imam in the palace though.

Then I realised my condition was getting critical, so I ate my breakfast to bring me to my senses. The four last things, that was what I ought to be thinking about. What were they?

Suddenly I thought of the woman with the baby in the park. If Frenchy couldn’t help the Leader, perhaps he’d go. Perhaps they’d lead a better life.

I paced the floor, wondering what was happening now.

This was what was happening…

*

Frenchy was bathed, dressed in a white linen robe with a red cloak and led down to the great hall.

The Leader was sitting on a dais in a heavy wooden chair. His arms were extended along the arms of the chair, his face held the familiar look of stern command, now a cracking facade covering decay and lunacy.

On his lips were traces of foam. Around him were his advisors, belted and booted, robed and capped or blonde and dressed in sub-valkyrie silk dresses. The court of the mad king—the atmosphere was hung with heavy incomprehensibilities. Led by her father and Karl Ossietz, Frenchy approached the dais.

“We—need—you—” the Leader grunted. His court held their places by will power. They were terrified, and with good reason. The hall had seen terrible things in the past year. There were, too, one or two faces blankly waiting for the outcome. As the old pack-leader sickens, the younger wolves start to plan.

“We — have — sought — you for — half a year,” the grating, half-human voice went on. “We need your predictions. We need your—health!”

His eyes stared into hers. He leapt up with a cry. “Help! Help! Help!” His voice rang round the hall. More foam appeared at his lips. His face twisted.

“Go forward to the Leader,” Karl Ossietz ordered.

Frenchy stepped forward. The court looked at her, hoping.

“Help! Help!” the mad, uncontrollable voice went on. He fell back, writhing on his throne.

“I can’t help,” she said in a clear voice.

Karl’s whisper came, smooth and terrifying, in her ear: “Go forward!”

She went forward, compelled by the voice. Then she stopped again.

“I can’t help.” She turned to Ossietz. “Can I, Karl? You can see?”

He stared at her in horror, then at the writhing man, making animal noises on the dais, then back at Frenchy Steiner.

“You—you—you have fallen…” he whispered. “No. No, she cannot help!” he called. “The girl is no longer a virgin—her power has gone!”

The court looked at the Leader, then at Frenchy.

In a moment, chaos had broken out. Women screamed —there was a rush to the heavy doors. Men’s voices rose, shouted. Then came the crack of the first gun, followed by others. In a moment the hall was milling and ringing with shots, groans and shouts.

On the dais, the Leader lay, twisting and uttering gutteral moans. The pack was at frenzied war. Those who had considered the Leader immortal—and many had —were bewildered, terrified. Those who had planned to succeed him now hardly knew what to do. Several of them shot themselves there and then.

*

I was lying on the bed smoking when Frenchy ran in, slammed and bolted the doors behind the guards and her pursuers. Her hair was dishevelled, she held the scarlet cloak round her. “Out of the window,” she yelled, ripping it off. Underneath, her white dress was in ribbons.

I got up on to the window-sill and helped her after me. I looked down towards the courtyard far below. I clung to the sill.

“Go on!”

I reached out and got a grip on a drainpipe. I began to slide down it, the metal chafing my hands. She followed.

At the bottom, I paused, helped her down the last few feet and pointed at a staff car that was parked near the gates. Guards had left the gates and were probably taking part in the indoor festivities. There was only one there and he hadn’t seen us. He was looking warily out along the road, as if expecting attack.

We skipped over the lawn and got into the car. I Started up.

At the gate, the guard, seeing a general’s insignia on the car, automatically stepped aside. Then he saw us, did a double-take, and it was too late. We roared down that road, away from there.

The road ahead was clear.

*

True to form, Frenchy had found and put on an officer’s white mac from the back seat.

I slowed down. There was no point in doing 80 toward any danger on the road.

“And have you lost your power?” I asked her.

“Don’t know,” she gave me an irresponsible grin.

“What was going on below? It sounded like a battlefield.”

She told me.

“The Leader’s finished. His successors are fighting among themselves. This is the end of the Thousand Year Reich.” She grinned again. “I did it.”

“Oh, come now,” I protested. “Anyway I think we’ll try to get back to England?”

”Why?”

“Because if the Empire’s crumbling, England will go first. It’s an island. “They’ll withdraw the legions to defend the Empire—it’s traditional.”

“Can we make it.”

“Not now. We’ll get out of Germany and then lie low for a few days until the news leaks out in France. Once things start to break down, the organisation will disintegrate and we’ll get help.”

We bowled on merrily, whistling and singing.

THE END

First published in New Worlds 143, July-August 1964. © The Estate of Hilary Bailey. Reproduced with permission.

• This page is part of the New Worlds Annex