I first met Barry Bayley in either 1955 or 56 at the old Globe Tavern near Leather Lane, which is the area I ‘expanded’ to contain the fictional Brookgate of several of my London stories. Barry frequently put me up at his place and we shared a flat together while working on an aborted novella for E.J. Carnell, ‘Duel Among the Wine-Green Suns’. We would once or twice a week meet J.G. Ballard in Kensington and we would talk about the boring conventions of science fiction and how we intended to change the world of literature as we knew it. We saw the best sf serving as some kind of potential marriage between literary and popular fiction. That remained our goal throughout this period. New Worlds was ready to go long before I was approached to edit it by David Warburton, who until then had been famous for publishing Hank Janson books. Barry and I were working writers, taking on pretty much anything we could get. This improved Barry’s speed and taught me to write as rapidly as I still more or less do. When you are running on daily and weekly deadlines, often with only a few hours to produce a piece, you learn to think on your feet and not get too self-conscious about an idea. There’ll always be another one along in a minute. Barry has a massive brain. It is too big for his skull. Once you could get him awake, you just thumped his head and two or three more ideas would spill out. I’d have them down on paper before he realised they were his. However, I had my compensations for being the dumb one in the partnership. Barry, who is frankly dwarfish in stature, and I, a tall, godlike blond giant, made strange company. I remember one day we were walking along King’s Road, Chelsea, when it was still an ordinary place to live, we glimpsed ourselves side by side in a shop mirror and fell about helplessly laughing. We were like two different species, almost. I always got the larger portions in the greasy spoons we ate in. I think the matronly waitresses had decided Barry was beyond fattening up.

Though we often thought very similarly and complemented each other’s imaginations—Barry’s logic, my romantic invention—Barry’s invention, my ability as a story-teller—we did not always share the same sense of humour. I remember Barry becoming positively puritanical during the episode in which I tried to set fire to the underground carriage in which we were all travelling. This led to a set of consequences recalled by, among others, Tom Disch when I was not quite at one with myself. If only there was such a thing as group amnesia, when you’ve made a total and highly memorable pratt of yourself. Barry, in these letters, is considerably forgiving, it seems to me. But I am sure I’ve been just as generous to him in some way or another. (Come to think of it, his bringing a drunken ‘friend’ he’d met in the pub to my house and friend being thoroughly sick face down in my bed, might help the balance). We’ve been friends for so long, you can take such things for granted. This is the beginning of a correspondence in which, knowing it to be for public consumption, we deliberately tried to recall our impressions of a past when the worst thing we had to worry about was the H-Bomb. Not, come to think of it, that many of us did worry much about it. We left that sort of thing to John Brunner, who wrote the CND marching song, ‘Don’t You Hear the H-Bomb’s Thunder’. Ballard had particular reason to be fond of the Bomb, as had Aldiss, and we were as interested in the things nuclear energy could power as we were in worrying about getting blown up. We hadn’t worried during the V-bomb raids on London and an H-Bomb was an altogether more humane alternative. We never learned to start worrying. We all loved technology, especially its potential for the arts, and that was why few of our stories ever debated the conventional worries of the day. Though, oddly, we were a lot more interested in ecology than those who dismissed our work as self-indulgent. We also, as Bayley has done, had a way of coming up with fundamental scientific notions which appear to escape most of the technical lads over at Analog, whose contributors were confidently predicting World Peace and the discovery of perpetual motion by the end of the 20th century. Anyway, rough and ready as it is, here’s our correspondence to date.

—Michael Moorcock

Michael Moorcock: What if I ask you if you can remember when and where we first met. Do you remember? Globe? Pete Taylor?

Barrington J. Bayley: Casting my creaky memory back half a century (it’s like my creaking hard drive, which has too little RAM support, so groans away and everything takes a long time), I started going to sf’s meeting place in the bar of the Globe in London’s Hatton Gardens while I was still in the RAF. The first person I ever met there was John Brunner, who spotted me hovering nervously in the doorway, advertising my fannishness by displaying a copy of New Worlds, and he invited me to join him.

Some time later, when I was out of the RAF, a large young man in flannel trousers turned up—you. I can remember our second meeting, but only very vaguely the first. I do remember that we became friends practically immediately. I was impressed by that Moorcockian determination: a professional writer and editor since leaving school at fifteen! You said (inaccurately) that you were purely commercial. It was a good attitude to take at the time.

Like everyone else I assumed you to be older than you were. I recall asking you, one day, how you had avoided National Military Service (which was in force at the time). I got no distinct answer beyond a sense of puzzlement. That was because you weren’t old enough for National Service yet!

Pete Taylor was a longstanding friend of yours and I became friends with him through you, though of course he also was a Globe attendee. I remember him saying to me once, ‘Never get rid of your collection, man. I got rid of my collection, and I could cry over it.’ I know now exactly how he felt.

The atmosphere in that dingy little bar, every Thursday night, was wonderful, a regular mixture of fans and professionals, so that you got to know almost everybody in London who took sf seriously. People would turn up there from all over the world. It’s something I’m very glad to have experienced, and since sf was not as generally accepted then as it is now, it’s probably something which will never be repeated.

Michael Moorcock: Your memory of all this is clearer than mine. I remember how stimulated I was by your intellectual ideas. I had never met anyone before who thought naturally like a philosopher! And who understood advanced scientific ideas so thoroughly. I am pretty sure that if I began as ‘commercial’, any early ambitions I got to do something else were a good deal inspired by you. We lived and worked together after I came back from Sweden. We tried to collaborate on a novella for Carnell called ‘Duel Among the Wine-Green Suns’. Parts of this found their way into The Sundered Worlds and parts into The Final Programme. You, of course, invented DUEL, the mighty computer, for ‘Duel Among the Wine-Green Suns,’ which I lifted whole for FP. But you also turned me on to the possibilities of computers and we used to discuss those huge cryogenic giants with awe, never quite realising we’d actually have a version in our own homes one day. Most of our collaborations, in fact, were exactly what I said—commercial. We did a lot of work together for the Fleetway Magazines. We did science, historical and natural history articles for Look and Learn and I wrote ‘The Life of Constantine the Great’ for Bible Story Weekly. I had the practical instincts, I suppose, of a working journalist. I expected to make a living from my writing. It was my job. Our first sale to New Worlds was a collaboration, too—was it ‘Going Home’?—and didn’t we also collaborate on a story published under Hilary Bailey’s name? Carnell had a prejudice against your work, so I suggested you use a pseudonym. You used the name of a friend. As I recall Carnell started buying your stories at once and sent the money to the friend. Not all that money came to you in the end! And when, as a kind of proof of his prejudice, I revealed to Carnell that this was really Barrington Bayley his response was ‘well I still don’t like Bayley’s work.’ So you were stuck with your dodgy friend. We lived together for a bit—or if you prefer, I squatted on your floor. We used to go to The Swan in Knightsbridge, near the offices of Chemistry and Industry, where Ballard worked, and meet once or twice a week to discuss how awful sf was, how awful modern fiction was, and what we could do with it. Do you remember persuading Carnell to run ‘The Terminal Beach’? The excitement with which we first read The Drowned World? Do you remember when you first met Ballard?

Barrington J. Bayley: Yes, I can see that we complemented each a great deal. I benefited rather more than you did, I think.

And yes, those gigantic computers! Something sf writers didn’t foresee was that electronics was going to become microscopic (well, someone did—there was a one-off story in New Worlds). Electronic machines were envisaged as getting huger and huger. I had a fight between a mobile building-sized ‘electronic brain’ and an equally big biological monster in one of my boys’ serials. Still, we bucked the trend in ‘Duel Among the Wine-Green Suns’. It had a cabinet-sized computer which could do world-scale simulation. We got around the size problem with ‘electron resonance plates’ (silicon chips hadn’t been invented yet.) They sound good, a bit like the quantum computers people talk about nowadays.

Something which makes me sniff about more recent sf is how it harps on about computer simulation and virtual reality and stuff (they keep doing it in Star Trek). It’s old hat to us. It was all in ‘Duel’! The reader isn’t sure at the end if the computer was only there to run simulations, or if the whole saga had taken place within it. Dear old Ted Carnell. He took the trouble once to write me a long letter explaining why he thought my stuff was hopeless. The gravamen, put over with much kindness and sympathy, was: you can’t write, you never could write, and you never will be able to write. I am a testament to the advantage of stupidity. I never listened to discouragement, but treated its sources to my favourite emotion, disdain (FYI: I live in Donnington because I can disdain ceaselessly). They never understood that I had no ambition to be a writer, because I already was a writer, had become a writer at the age of fourteen. So there.

I dimly remember our being in Carnell’s office and discussing Ballard’s novel, which Ted was doubtful about—probably because it was so good!—but it must have been mainly you who persuaded him to use it. Ted wouldn’t have heeded me. The only time he ever asked my opinion was when he was terribly upset over a cranky letter he had received trashing New Worlds, saying it contained only rubbish, took only twenty minutes to read, and wasn’t worth the money. I told him he was bound to get letters like that, it was part of being an editor, and he shouldn’t worry about it. What I really wanted to say was, you should use my stuff, then! One of Ted’s criticisms of my stories was the way I treated the whole universe as mankind’s backyard.

I think our first New Worlds collaboration was ‘Peace on Earth’. It was about death, and its place in life. Did we do a Hilary Bailey story? I vaguely remember doing some work on one she had written, about people turning into ants. Was that it?

When my ‘dodgy friend’ wrote to confess why I wasn’t getting the New Worlds money (he had been spending it) I used his letter in a new story. So that was one he really did co-author!

I recall with fondness the daytime pub meetings with Jim Ballard, and a friend of his whose name I forget, who was very shy. He and Jim had worked out a private philosophical vocabulary between them. Jim referred to some idea, and his friend replied, ‘That’s very spinal.’

I can’t remember where and when I first met Ballard, but it was almost certainly through you. You made it your business to get to know writers who interested you. You would write to them and introduce yourself. I still remember T.H. White’s reply when you asked him for advice to a young writer wanting to improve. It’s the advice I now give: Read, read, read!

It was you who first enabled me to make a living as a writer (as apart from starving and owing the rent) by introducing me to the juvenile field, which was great fun. Do you remember our rubber stamp when we were in partnership? You also wrote a letter of introduction to Don Wollheim when I wanted to start writing novels. He was sf editor at Ace Books then. I had written a couple of these for him, I think, when I first met him in the flesh in the English town of Worcester. His eyes shone. “Barrington Bayley? You really exist? I thought you were Mike Moorcock masquerading under another name!” He explained that your output was so enormous he had believed you had adopted a second identity to help market it.

Not the only time I have been compared with your shadow!

Michael Moorcock: You are kind—but what’s this ‘we’ worked out—you fucking worked it all out. I’m too dumb for that.

Barrington J. Bayley: Listen to this. There’s a story in one of your Millennium omnibus editions (don’t know the title as I can’t lay my hands on it) in which the galaxy is slowly being eaten up by a huge object at its centre, which you didn’t actually call a black hole, probably because the term hadn’t been coined yet. At the time I would guess it was written, nobody knew that galaxies have black holes in the middle. Furthermore, astrophysicists then thought the expanded universe would eventually fall together again by gravitational attraction. Guess what? Recent measurements show that there isn’t enough matter to do it! The galaxies will just carry on receding until they are all swallowed by their black holes. And who thought of it first? You did!

Michael Moorcock: Let’s do another long chunk of this reminiscence to take us up, say to the start of New Worlds.

Barrington J. Bayley: Events are a bit too scrambled in my mind. I’ll burble on for a bit.

You’d introduced me to Dave Gregory at Fleetway, which published boys’ papers among other things, and he started giving me work. One day he agreed an outline for a picture strip story. I think it was an ‘Olac the Gladiator’ (a house character) story set in Roman times. Well, I’d never done any picture story scripting before, although you’d already shown me the layout. You were sleeping on my floor at the time. The day after (when the script had to be written) you got up, announced you were off somewhere, and made some helpful suggestions. Then you must have realized that I didn’t really have a clue how to do it, because you took pity on me and stayed behind, and we wrote the script together. Next day I toddled into Dave’s office and he read it. I told him we’d co-authored, but he plainly believed it was all your work (well, he was three-quarters right); it must have been too practised and professional. To catch me out, he asked me to write a few inserted frames on the office typewriter. He seemed quite surprised that I could actually do it!

We regularly co-authored picture scripts after that, but you had flair for it—pictorial imagination, snappy dialogue—and my role would be more tightening up the sequence a bit. I carried on after we separated, but I never really felt confident with comics. I was happier with text. Luckily there was plenty of that work to be had as well.

Fleetway would sometimes get Italian artists to draw the comics. But the translated instructions were only the picture descriptions, not the stories. Consequently the artist didn’t know what expressions to put on the characters’ faces!

Michael Moorcock: We worked with some talented artists. Frank Hampson, the Embletons, Don Lawrence, Frank Bellamy, pretty much with all the best graphic artists of their day. It was more like the studio system in films or the production of two and a half minutes singles. Not much room for self-expression. I used to keep myself awake by doing Karl the Viking stuff in Anglo Saxon alliterative verse. I told Dave Gregory about that eventually and his comment was ‘I thought you were writing a bit funny’. He, of course, had sensibly edited it to proper comic English. We did a lot of lost city pieces, as I recall, and also I did a whole series on the Cathedrals of England for Bible Story. You were writing ‘The Man from T.I.G.E.R.’ for Tiger. We would occasionally pass on work, because it was never by-lined. I remember the horror we felt when Boys World started crediting authors. I think at least one of my short stories appeared under your name. A problem for future bibliographers! Another thing you taught me, in a way, was how to sit still and think!

Barrington J. Bayley: Round about then you married Hilary Bailey, and set up home three times in succession, coincidentally coming closer to where I lived each time. One day you phoned me up and said ‘I’m now editor of New Worlds.’ Kyril Bonfiglioni (I heard about him on the radio the other day, but I can’t remember what. I think it was a books programme) took on one of the sister magazines (Science Fantasy, later SF Impulse). Your editorship ideas were all a transformation of New Worlds. Even the cover designs were original. Questions were raised in the House of Commons objecting to the content of a Norman Spinrad serial!

Michael Moorcock: I remember—the days when we all used to be taken seriously. Before we seemed to drown in a tide of juvenilia…

Barrington J. Bayley: Your flat and Ladbroke Grove in general became a dynamo and a magnet for the sf world. Jim Cawthorn, Graham Hall, Charles Platt, Judy Merril, Graham Charnock, Bert Filer, John Sladek and Tom Disch all ended up living close by—Judy and Tom in the same house as myself, just along the road.

Michael Moorcock: I used to call on Judy and she always had some famous old jazzman, who was playing at Ronnie Scott’s or somewhere. I’ll swear I bumped into Buck Clayton, pulling on his pants and leaving with a mumbled greeting…

Barrington J. Bayley: One day I called on you carrying a typescript (it wasn’t in the Ladbroke Grove flat, but the previous one). It was a story I had written in draft some years before, but I had regarded it as unpublishable: ‘All the King’s Men’. I wouldn’t have dreamed of offering it to Ted Carnell! Because I liked the story myself, I had just revised it and typed a fair copy.

As I remember, I wasn’t submitting it, only wanting your opinion. You took it in your hand, but then announced that you needed to use the toilet, and would read it in there.

You’ve had to suffer several instances of odd behaviour from me, but now I can explain this one. I became almost hysterical, snatched the typescript back, and simply would not allow you to take it into the toilet with you.

I recall your look of mystification. Knowing you weren’t aware it was the only copy—not expecting to see it published, I hadn’t bothered taking a carbon—and knowing your sense of humour, I felt absolutely, totally certain that Moorcock would emerge from the toilet wearing a smug smile, and saying, “Well, there wasn’t any toilet paper.” And the story would be lost.

I still think it! How irrational am I?

Michael Moorcock: I couldn’t possibly have used the whole manuscript. I put it in New Worlds instead. One of our most popular stories and it blew Mike Harrison’s mind, as I recall. Your aliens were the inspiration for his early science fantasies. And while you were knocking Harrison’s brains out in the UK, there was a whole group of young writers based around Austin, Texas, who were beginning to speak of you as if you were a god. You produced your masterly Soul of the Robot, Knights of the Limits and The Garments of Caen, amongst others. You are, in many people’s eyes, the First Cyberpunk. But then you’re probably the first New Waver, too, for that matter. And you’re still turning out the most astonishing, unexpected stories, like ‘Love in Backspace,’ which remains one of my very favourites of your short stories. Let’s carry on with some more stuff about the New Worlds days later.

Michael Moorcock: I was thinking of our fascination with pseudo-science and how we found ourselves meeting some odd people in those early days. I remember that you independently invented the famous Dean non-reaction drive which John W. Campbell publicised in Astounding in the 1960s. So you were able to refute Dean fairly swiftly! Do you remember that? How old were you when you came up with the idea originally?

Barrington J. Bayley: Yes, in my mid-teens, I think. I’m one of countless people to have got the same crackpot idea, including I believe rocket pioneer Goddard, America’s counterpart of von Braun. My diagrams were identical to ones later published by Campbell and to descriptions of Dean’s design. I imagined two counter-rotating ellipsoidal weighted rotors with movable axes of rotation able to take up positions in the centre and both extremities of the rotors, so that the rotors’ upswing would consistently involve the greater mass. At the same time each rotor would restrain the other from turning about its centre of gravity. I was never naïve enough to think Newton’s third law of motion could be sidestepped so easily, but what puzzled me for quite a long time was that I couldn’t see why it wouldn’t work. Whenever I tried to follow the interplay of forces the result seemed to be a net impulse in one direction. It was a case of not seeing the wood for the trees. A connected system still has a centre of gravity, now matter how its parts are rearranged.

Dean is one ‘inventor’ of the non-reaction drive who went ahead and tried to construct it. I remember you and I talking one day to a visiting American who had met Dean (can you remember who that was?) and had him demonstrate his gadget crawling along the floor, forgetting, I would presume, that the floor gave it something to react against. Such a gadget would travel even if mounted on a trolley (I myself have crossed a room standing on a small trolley, holding on to the hand rail and jerking back and forth). Given enough power, it could leap into the air (only to fall back down again).

Michael Moorcock: I think the visiting American who told us about the Dean Drive might have been Burt Filer. Or was it before we met Burt?

Barrington J. Bayley: The guy who met Dean was someone I never heard of before and would have no idea of his name now, so Burt Filer is a possibility, though that might be a young sf writer who came along later and asked me did I write science fantasy or clank-clank (his term for hard sf). He pronounced himself a writer of clank-clank.

Michael Moorcock: Sounds like Burt’s sense of humour. He was the first person I ever met who made a living as an inventor. When asked what he did, he said ‘I’m an inventor’. He’d designed some interesting stuff and sold his patents to a backer who specialised in payrolling inventors! He was building a circular flute the last I saw of him. He had the model all ready. It was designed to increase the range of the conventional flute without extending the tube, as it were. Mike Harrison and I went up to Scotland with Burt, walking around Ben Nevis. It was a great trip, even if Burt nearly got bashed to bits by a bunch of repressed Scots at a Saturday Night Dance. He tried to pick up a girl, not knowing that all the girls stuck together on one side of the floor and all the lads on the other, yet many of them were engaged! Mike and I had warned him. We left the dance early but Burt was determined. Next we saw of him he was pale and shaken while downstairs outside some poor bugger was getting the shit beaten out of him (maybe Burt’s substitute). I went down to try to help the bloke and all the bouncers were inside, hiding. I got out there eventually and all I found was blood and a pair of smashed glasses… Burt got involved with a school-teacher in London and slipped off into the night. I remember that he had a bit part in the movie of Death of Grass (Cornell Wilde!) because he could ride a motorbike. Wonder what happened to him. Maybe he was swallowed by one of his own inventions. The Moebius Flute? I know he shared our enjoyment of wacky pseudo-science.

Barrington J. Bayley: Pseudo-science is a fascinating field, synthesised from the elaborated development of the exact sciences and an inexhaustible human resource: looniness. It’s a sort of mixture of hopefulness and ‘scientism’: an imagined idea of hard knowledge. We are going to see more and more of it mixed with ill-disciplined experimentation (recent examples are the ‘cold fusion’ and ‘memory water’ claims).

In West Kensington library I found a delightful book written by, an Austrian I think, who had invented a machine for producing limitless energy out of nothing. He called it ‘the stator’ and had tried to persuade the UK government to fund its construction, offering to defend the British Empire. I can’t remember the principle on which it was to work, but like the Dean Drive it almost certainly depended on a delirious overthrowing of the basic principles of physics.

Campbell also championed what in Britain is known as radionics, developed by de la Warr (maybe that’s the other machine you mention). I’ve read one of de la Warr’s books. He comes across as probably a likeable and sincere person, but quite nutty. When confronted with an experimental result which contradicted his theory (he tried to kill disease bacteria with ‘radionic radiation’) he wrestled with his soul until he came up with a radionics-saving explanation. And he soon learned not to go near medical scientists who offered to subject his claims to clinical trials.

Current radionics practitioners I know of are not nice, however: evil charlatans exploiting sick, desperate people for mercenary gain and sexual predation.

It would be comforting to think that ‘real scientists’ are completely sane and well-balanced, but alas it is not so. That kind of level-headedness is restricted to us science fiction writers, as far as I can see! (Yet how often have you been targeted with the exasperated words, ‘But you must believe in flying saucers! You’re in science fiction!’) The towering intellect of the scientific age, Newton, was distinctly odd. I wonder if the years he spent labouring in his alchemical laboratory, which must have involved long-term exposure to mercury, might have had something to do with his subsequent mental breakdown. His later years were devoted to Biblical exegesis, from which he calculated the world is scheduled to end in 2060 AD. Beat that for divorce from reality!

Michael Moorcock: Remember that guy who gave us a go on the E-meter and how we learned it was an old US Army lie detector which could be bought cheaply as army surplus?

Barrington J. Bayley: He was a young Dane or Swede called Jan, if I remember. It was you who had the e-meter ‘processing’; I wasn’t there (maybe you could talk about it). But he was quite an engaging fellow and I used to run into him in a cafe near Notting Hill tube I used sometimes.

Late one night a big goony guy came rushing in, pent up, yelling ‘I need you, Jan! Now!’ Jan promised to come round to him as soon as he had finished eating. I took him to be one of Jan’s scientology clients and thought, Wow, this thing really builds up dependency. But he turned out to be somebody Jan had rented a room to next to his own along the street, and was unhappy about the arrangement. Jan became nervous and was glad to accept my offer to accompany him back. When we got there the two of them started arguing in scientology speak (he accused Jan of ‘playing a low-tone game’) but Jan was better at it and soon was able to manipulate him.

Another night we were standing chatting on the corner having come out of the same cafe when an elderly, very well-dressed man collapsed on the pavement, clinging to a lamp-post and begging hoarsely, ‘Please don’t let me die in the street.’ I thought Jan’s total lack of reaction rather callous. I nipped into the tube station and phoned for an ambulance. When I got back Jan was still there, but the old fellow had gone. It seems a couple of coppers had come along, yanked him to his feet and hauled him off to a taxi drivers’ hut there was nearby. They were familiar with him and his sympathy act. ‘I knew straight away he was a fake,’ Jan said cheerily. ‘Still, you played an interesting game, Barry.’ (Everything to a scientologist is a game, apparently.) Then I had to explain it to the ambulance men.

Jan related a similar incident. ‘I was walking along and came to a knot of people gathered round a young woman lying on the pavement. None of them knew what to do.’ Jan used his scientology training. ‘I went up to her and said, ‘What is it you want?’ She said, ‘I want two shillings for my fare home.’ I gave it to her and she got up and walked away.’ A ‘touch assist’ in reverse!

Jan needed a job and an acquaintance of mine told me of an opening where he worked, so I made introductions, and he to his (Jewish) employer. Later Jan phoned me. ‘This old Jew is a really square fellow, Barry.’ It seems he had wanted Jan to work without pay and live off social security until he had learned the job (silk screen printing). Probably, though, he could see Jan wouldn’t stick it, and wanted to get rid of him.

Although Jan was keenly interested in ‘self-development’, I don’t think he took scientology very seriously. He told me he’d gone all the way through to ‘power processing’, whatever that is, and concluded it was a lot of fuss about nothing. He showed me a list of rules and instructions written by Hubbard for a course he had taken. They started off quite cogently (one was a ban on sexual liaisons with classmates), then towards the end became rambling. When I pointed this out, Jan said it was typical of Hubbard.

As far as I can make out the E-meter puts a small voltage across the skin and uses a galvanometer to measure the resultant current. It would only cost a few pounds to make, though I’ve read Hubbard made an enormous profit on it. Human skin’s electrical resistance changes in response to emotional reaction (perhaps because the sweat glands then secrete, water being a good conductor), a phenomenon which is promising as a lie detector. I think it’s one part, together with monitoring of blood pressure and heart rate, of the reputedly unreliable polygraph the US police use. Scientologists, however, claim to be expert interpreters of the needle’s movements. Remember Glyn Davies, the astrologer and Cabalist? He told me he had met some scientologists who were praising the E-meter’s powers, which Glyn, after his habit, scoffed. ‘All right.’ they said, ‘Let’s see if we can find out your birthdate.’ (This is nothing too impressive. A trained stage magician can find out your name, birthdate, etc. by observing your involuntary reactions to questions.) What they hadn’t known was that Glyn himself didn’t know when he was born. So he made up a date and tried to ‘hide’ it in his mind. And of course they found it.

Michael Moorcock: Jan had this list of typed questions to ask. They were supposed to measure engrams. But the questions were all highly emotive. ‘Do you love your father?’ Stuff like that. Naturally you were going to respond fairly dramatically, as far as the needle on the ‘e-meter’ was concerned. It was such an obvious fraud. I don’t remember Jan doing anything but agree. I know I was incredulous then that sf people should have bought the notion. Since then, of course, lots of people have bought it. All these cults seem to operate on a miserably low level. Makes you realise that there aren’t that many smart people about! Or if they are there’s a hefty proportion of them are soup sandwiches. We’re already living down the rabbit hole. Nobody remembers anything. One nutty cult follows another. The same issues are recirculated in the press about every twenty-five years (if not more rapidly). Depressing, really, all those famous film stars and people who put so much of their money into that stuff. Maybe we should have learned our lesson in those early days and taken a leaf out of Hubbard’s book. As it is, we almost starved in near-garrets and saw our hunger-crazed notions patented by others! Just like Arthur Clarke. We hard sf guys have got a lot to be bitter about. Still, there’s something very attractive about loonies, especially the harmless ones.

Barrington J. Bayley: Did you know that one of the natural philosophy clubs which promoted science centuries ago called itself The Lunatic Society? But that was because its members travelled the countryside at night to meet up, and so met during the full moon.

Our own lifetimes have seen the emergence of a whole living class of ‘mad scientists’ in the Nazi era, of course. I think future generations will see more of that.

Michael Moorcock: I think you’re right. A new breed of ‘Elmer Gantry’ demagogues. I remember having a go on some other machine Campbell, the Astounding/Analog editor, brought to the 1965 World Science Fiction Convention in London, where he discovered logical opposition to his ideas apparently for the first time. I was on a panel with him. He blustered about various nonsensical notions, including his own ‘barbarian’ ancestors (apparently unaware of the nature of the traitor Campbells!) and then called on God to be his witness, since nobody else would be. An extraordinary display, rather prefiguring Doctor Strangelove in some ways!

And those old sci-fi buffs said we weren’t interested in technology! I remember how we seemed to be the first sf writers seriously interested in computers. Remember the compact computer we had in our unpublished ‘Duel Among the Wine-Green Suns’, which I later put into The Final Programme. ‘Duel’! I was reading an article somewhere, while researching for a short article I was doing on science fiction predicting real science (pretty poor show all in all) that writers hadn’t anticipated the PC at all. We didn’t do that, but we did shrink at least one computer to manageable size (even if the parties inside believed they were ‘real’) while otherwise dealing with those massive old cryogenic Leos and so on. I wonder why so few writers anticipated computers and not one of us anticipated the PC, as far as I know.

Barrington J. Bayley: Well, in a novel of yours you serialised in New Worlds (the protagonist was able to tunnel between realities) someone was using a portable computer while a passenger in a car. So it’s not true none of us anticipated the PC. You anticipated the laptop!

(You also anticipated the current view that every galaxy has a black hole at its centre which eventually will devour it, leaving the universe devoid of anything but black holes.)

But it does seem true that sf writers generally failed to foresee the current state of computing. This is because they imagined electronic machines would get bigger and bigger, whereas they got smaller and smaller. A pulp mag novel which impressed me when young was Raymond F. Jones’s The Cybernetic Brains in Startling Stories. It depicted a future in which the brains of dead people were used as control systems for industrial processes, it not being known that thereby the brains became conscious again and went insane through being unable to communicate. About then, I read an article discussing how small a thermionic valve might be made. Could it be made as small as a grain of rice? It got replaced by the transistor, of which there are thousands on a chip.

Michael Moorcock: We came up with ‘Duel’ around 1961 didn’t we, while I was staying with you at the House of Usher. The whole place would shake when even a motorbike went by outside and the landlord’s name actually was Usher. I was in a sleeping bag on your floor. I used to open my eyes slowly in the morning so as not to disturb the mice who had gathered around to stare at me. I felt a bit like Gulliver. I think it was you who discovered we could get maximum protein for the least money by buying bacon scraps from the local butcher. I remember being stimulated by your ideas a lot during that period. I also remember how much we put in to ‘Duel Among the Wine-Green Suns’ and how shattered we were when Carnell rejected it.

Barrington J. Bayley: I seem to remember the genesis of ‘Wine-Green Suns’ was material you wrote immediately after returning from Sweden where you lived for a while, or brought back from there. Its computer or ‘facsimile cabinet’ for rehearsing societies, personalities and wars was an early if unpublished prefiguring of the misnamed ‘virtual reality’ that has become commonplace ever since Gibson’s Neuromancer (the current film version is The Matrix) though I say that with trepidation, as somebody likely knows of other cases. Mind you, this “virtual reality” is only the computer-age version of the older sf theme where the characters contend in a shared dream. In ‘Wine-Green Suns’ the reader is left not knowing if the fabulous story really did take place or is a rehearsal in the facsimile cabinet. As we said before, as silicon chips hadn’t been invented, miniaturisation was achieved by means of “electron resonance plates”. My idea was that electron quantum states could be used to hold information stored and retrieved by “resonance”. It’s more or less the same idea as the quantum computer people are now trying to develop, which if feasible will make present-day computers look like a two-string abacus. I think they’ve probably got it to add one and zero so far.

Those mice, of which the house had droves, were very canny. One hint of human movement and they were off through their holes with unbelievable speed. They could also leap from the floor on to the table top (either that or they could walk up vertical surfaces and along the undersides of horizontal ones). Yes, I recall that getting something to eat was occasionally a problem in those days. Later I became adept at living on 10 shillings (50p) a week, and that included paraffin for the heater (as well as a big heap of bacon scraps). One day, in the same house, we had invited Pete Taylor to ‘dinner’. I was quite perturbed when you impressed on me, in some anxiety, that Pete would actually expect to be fed. Somehow we found enough money to buy some potatoes and something to go with them. On another occasion we gathered together all edible resources for something to eat that day. I can’t remember what I ate, but you ate a bowl of cocoa powder mixed with sugar. This was a familiar repast for me; I’d once lived on it for three days. I remember this occasion, though, because of you’re asking, in a sing-song voice, ‘How eat cocoa powder with chopsticks?’

You used to enjoy your ability to reduce me to a collapsed heap of uncontrollable laughter. One day you launched into a skit of what these days is known as a ‘wigger’—a white man trying to enter black American culture. Your spiel ended with: ‘Just ’cos ah’m white don’t mean to say ah ain’t black!’

Michael Moorcock: After that it was Look and Learn for a while and ‘Round the Universe on a Ray of Light’ (one of yours) or ‘Anudhaphura; Lost City in the Jungle (one of mine). We had a living to write. Remember going to see that guy who was then editing Eagle and saying we wanted to get Dan Dare back to his former glory. He told us Dan Dare was fine as he was and it was just nostalgia on our part. Poor Frank Hampson, the creator of Dare, was thoroughly screwed by them. They essentially used him and threw him out. His self-confidence was so poor he never really got close to his glory days again. Remember when we suggested Boys World give away a B-52 bomber as a prize in competition? You could buy them for next to nothing, apparently. We pointed out that you’d never have to deliver since the kids’ parents would never allow them to have the plane in the back garden. Did you have any favourite stories you were writing then or were they pretty much all journeyman work?

Barrington J. Bayley: It would have to have been a B-29. The Yanks are still using their B-52s to kill people! I do remember our bravely complaining to Eagle’s editor of the sadly deteriorated Dan Dare strip. Maybe that’s why we never got much work there! As for all those stories, I recall being pleased with some I did, but there were so many it’s hard to know what, although the Astounding Jason Hyde serial, which ran for three years, had its moments. Juha Lindroos recently sent me a story from an old annual supposed to be mine. As it’s derived from another of my serials it probably is, but I couldn’t recognise it, not at all. If it was mine (or yours) it had been seriously mauled by the copy editor. I don’t believe either of us would have left the reader without the information necessary for the story to make sense.

A story I do remember was ‘Tunnel to the Moon’, about a tunnel from Earth to the moon through which trains ran and airliners flew. But I remember it because my wife Joan turned out to have read it!

One thing that did happen through doing that stuff was that I learned to write more and more quickly (a trick I have now forgotten). The weekly paper Valiant, in which the Jason Hyde serial ran, planned a “boom” issue and asked me to turn in two episodes that week. Late one morning I got a phone call.

‘Do you have those two episodes yet?’

You like to seem reliable, so I said, ‘Yes.’

‘We’ve got a flap on. Can you bring them into the office by two o’clock?’

‘All right,’ I heard myself saying, feeling no doubt of it. So I sat at the typewriter and wrote two episodes (five thousand words) in two hours, without even feeling the strain. Nuthin’ to it! To you, of course, that’s a regular pace.

Michael Moorcock: In the sixties a lot of hippies were convinced I’d written those books on acid. I used to have to tell them that I’d done it on adrenaline, sugar and caffeine. It’s a wonderful banisher of self-consciousness that kind of work but, of course, it helps to know it’s all being published anonymously. I remember how horrified we were when we discovered that we were getting by-lines to some of our work! Especially since you’d written under my name or I’d written under yours. And now, as you say, people show us the stuff and we actually don’t know whether it was us or somebody adapting something of ours. And was a regular pace is the operative word there. Having neither the deadlines, the anxiety nor the sugar and caffeine, I tend to go at a relatively slow pace, these days. My last Elric novels actually took months. I think that’s the first time a fantasy novel has gone over a month. Not worth doing any more. Maybe that’s why I’m not planning to write another after the next. Maybe we should start trying to collaborate again, now that we’re getting closer in speed. What do you think?

I wonder why we collaborated so successfully. We got on from the first time we met. I know that interest in barmy science is one of the things which helped us get on so well when we first met. Where was that? I suspect we met at the Globe. I know we hit it off immediately. I’m trying to think of the first story I read of yours and I think it was one of those you published in Vargo Statten’s Magazine when you were still a teenager. We both shared that precocity but your career was sadly interrupted by doing National Service (which I barely escaped, having wasted time in the Air Training Corps in anticipation of a call-up which never came). I know I found your ideas fascinating and highly stimulating. I think they definitely raised the level of my ambition. You seemed the most erudite person I’d ever met. You introduced me to a lot of very different writers from Hesse to Balzac. Extraordinary, really.

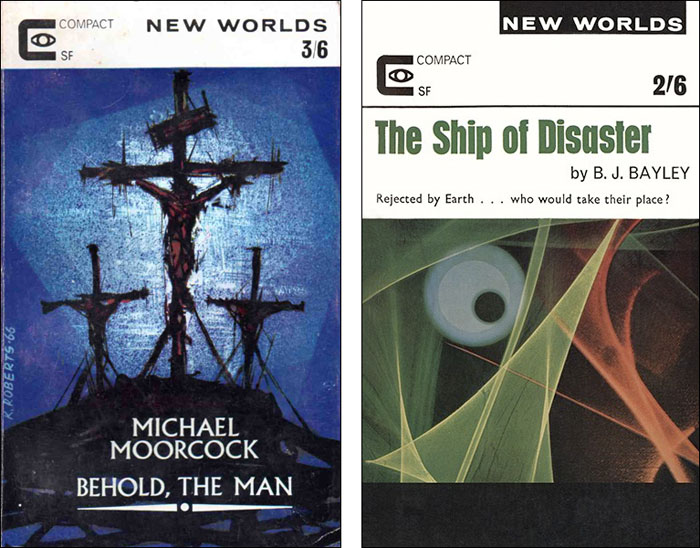

Barrington J. Bayley: Let me make a little disclosure. I recall when you and I met up with Jim Cawthorn and you described to him a fantasy story you were working on, involving the hero’s sister who was in a permanent sleep (wasn’t this the inception of the whole Elric saga?). Seeing Jim’s fascination (and feeling my own), I thought, I’d like to do that! I’d like to meet with friends and tell them about a story I’m working on and get this kind of reaction. Some years later I was writing “The Ship of Disaster”, a story I never would have written without being influenced by you, as it has elves and trolls in it. I used to hear you talking of elves, ‘eyes gazing into infinity’. We were at the Globe and I started telling you and someone else about it (could have been Jim!). I was knowingly playing the role I had promised myself a few years before, getting your attention, getting the approving murmur ‘sounds good’. Of such small triumphs is life made!

Michael Moorcock: Well, it’s better than worrying I was going to take it into the toilet and dispose of it (as with “All The King’s Men”). I published ‘Ship of Disaster’ in New Worlds 151. Not long after I’d taken over the magazine. I remember the response was tremendous. Mike Harrison said, as I recall, that ‘Ship of Disaster’ and ‘All The King’s Men’ were two of the most stimulating sf stories he’d ever read. When he was doing his own early work he said that a lot of what he was trying to do was reproduce the frisson he’d felt. So clearly you had your wish granted more than you’d hoped. Dave Britton says the same about that story, how it made him shiver. Nobody expected you to do an elves and trolls story which was not only science fiction but also had your familiar philosophical content. A great story. Was it reprinted in one of your collections? We ought to reprint it somewhere, if not. Certainly I had the same response when you were telling me about The Soul of the Robot. Your ideas just knocked me out. Not because you had the idea of robot discovering his soul, as it were, but because of the quality of your thinking. This is something not mentioned enough, I think. You could also discover the essence of something in another writer’s story and sometimes make the story sound a lot more interesting than it was. There was a James Blish story you liked in one of the pulps, Planet or Super Science or Thrilling Wonder—the magazines which published what people these days call ‘cross-over’ fiction—a bit of everything in those stories, which is why I always preferred them to Analog and the rest. That’s certainly where I read the Leigh Brackett stories which combined fantasy, horror, science and, being Leigh, a bit of western thrown in as well (all written in a noir-ish prose which she did her detective stories in—the stories which made Hawks want to use her on the script for The Big Sleep). Maybe that was another enthusiasm which brought us together. Speaking of which, I wonder, too, whether you’d read Mervyn Peake before we met. And had you read Peake by the time I first took you round to Drayton Gardens to meet Maeve?

Barry became ill and distracted by his wife Joan’s deteriorating mental health and so this ‘chat’ was set aside until we had more leisure. That never came for Barry. He died in hospital in 2008 of complications following an operation for bowel cancer. He is deeply missed. The Ship of Disaster and All the King’s Men (in New Worlds) were highly influential, especially on M.J. Harrison. There are plans to reprint his profoundly original novels and short stories. These conversations were originally published in Fantastic Metropolis. Barry’s fiction, including two volumes of short stories, is available on Kindle.

Copyright © 2003 by Barrington J. Bayley and Michael Moorcock.

• This page is part of the New Worlds Annex