Powell & Pressburger reworked for the stage

A Matter of Life and Death and theatre.

Category: {theatre}

Theatre

The Maids murder mystery

The Maids murder mystery

Neil Bartlett’s new production of Genet.

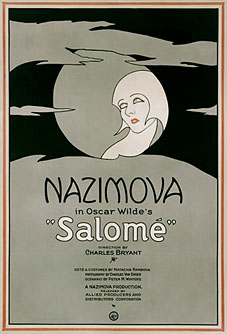

Alla Nazimova’s Salomé

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or femme fatale was an idea that gripped the Decadent imagination, and it found a living expression in the vamps of the silent era, beautiful women with exotic names such as Pola Negri, Musidora (Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampires) and the woman the studios and press named simply “the Vamp”, Theda Bara (real name Theodosia Burr Goodman).

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or femme fatale was an idea that gripped the Decadent imagination, and it found a living expression in the vamps of the silent era, beautiful women with exotic names such as Pola Negri, Musidora (Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampires) and the woman the studios and press named simply “the Vamp”, Theda Bara (real name Theodosia Burr Goodman).

Alla Nazimova was another of these exotic creatures, and rather more exotic than most since she was at least a genuine Russian, even if she also had to amend her given name (Mariam Edez Adelaida Leventon) to exaggerate the effect. Like an opera diva or a great ballerina she dropped her forename as her career progressed, and is billed as Nazimova only in her 1923 screen adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play, Salomé. Nazimova inaugurated the project, produced it and even part-financed it since the studios, increasingly worried by pressure from moral campaigners, regarded it as a dangerously decadent work. Nazimova had a rather colourful off-screen life and the stories of orgiastic revels at her mansion, the Garden of Allah, probably didn’t help matters.

Salomé lobby card (1923).

The 14-Hour Technicolor Dream revisited

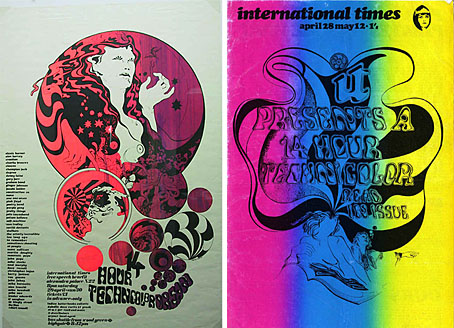

left: event poster by Hapshash & the Coloured Coat.

right: International Times 14-Hour Technicolor Dream special issue, April 1967.

The ICA goes psychedelic, baby. Lucky Londoners get to gorge themselves on this lot next Saturday.

2007 is a year of many anniversaries: twenty years since Acid House, thirty since the release of Never Mind The Bollocks, forty since Sgt. Pepper’s and fifty since the publication of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road.

One event that gets far less publicity, but that was at the heart of everything that came both before and after it also sees its 40th anniversary this year. The 14-Hour Technicolor Dream took place on April the 29th 1967 and was the UK’s first mass-participational all-night psychedelic freakout!

Organised and in a matter of weeks, the event was held in the cavernous confines of Alexandra Palace. The vision of Hoppy Hopkins and Miles, the night saw a glorious mingling of freaks, beats, mods, squares, proto-punks, pop stars and heads come together to dance, trip, love and be.

To celebrate the anniversary, the ICA presents Our Technicolor Dream—a one-off multi-media event that features an array of cult 60s films and animation, full-on psychedelic lightshows, groovy DJs, avant-garde theatre, a Q&A session with the leading lights of the 60s underground and live music with The Amazing World of Arthur Brown, The Pretty Things, Circulus and Mick Farren!

• Tell It Like It Was: The Round Table Speaks: Joe Boyd, Miles, Hoppy Hopkins & John Dunbar.

• Freak Out, Ethel! An Evening of Musical Mayhem: Malcolm Boyle’s play plus The Amazing World of Arthur Brown, Circulus, The Pretty Things and Optikinetics lightshow.

• Boyle Family Films With Music by The Soft Machine

• Weird and Wonderful 60s Animation: Films by Jan Lenica, Jan Svankmajer, Walerian Borowczyk, Chris Marker and Ryan Larkin.

• What’s A Happening? “90 minutes of rare, lost and unseen psychedelic masterpieces”.

Retrospective newspaper features: The Independent | The Times

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Verner Panton’s Visiona II

• The art of Yayoi Kusama

• All you need is…

• Sans Soleil

• Summer of Love Redux

• The Invasion of Thunderbolt Pagoda

• Oz magazine, 1967–73

• Strange Things Are Happening, 1988–1990

Joe Orton

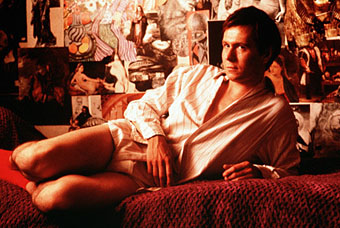

Gary Oldman as Joe Orton in Prick Up Your Ears (1987).

Ken: At least you can say you’ve sat in the same chair as TS Eliot.

Joe: Yes, I’m never going to wipe my bum again.

Gay playwright Joe Orton receives a welcome renewal of attention this month with a showing of films at the ICA in London and the 20th anniversary re-release of Prick Up Your Ears, the great Orton biopic by Alan Bennett and Stephen Frears. Gary Oldman is marvellously sexy (and funny) as Orton in Frears’ film, Alfred Molina is equally good as his increasingly neurotic lover, Kenneth Halliwell (who eventually murdered Orton before killing himself), and there’s decent casting throughout, with Vanessa Redgrave playing Peggy Ramsay and Julie Walters hilarious as Orton’s mother.

Prick Up Your Ears was originally Halliwell’s title for a script Orton was writing for the Beatles (“…much too good a title to waste on a film,” said Orton.) That film idea, variously titled Up Against It and 8 Arms To Hold You, was deemed “too gay” by McCartney and co., not least because Orton had all four Beatles sleeping in the same bed. He also wrote that “…the boys, in my script, have been caught in flagrante, become involved in dubious political activity, dressed as women, committed murder, been put in prison and committed adultery. And the script isn’t finished yet.” Now you know why the third Beatles film was an animated one.

A feature in The Guardian examining Orton’s legacy, as well as the film, has this to say of Prick Up Your Ears:

it was the first mainstream British film to depict the gay underworld of West End toilets and sign language that existed in an age when homosexuality was still illegal.

And much of it was filmed on location in Orton’s haunts. Every time I’ve been through Islington tube station I think of the scene where Gary Oldman picks up a guy he’s been eying in the lift.

Orton had the misfortune to die in 1967, the year homosexuality was decriminalised in Britain. Well… decriminalised so long as you were both 21, not members of the Armed Forces and there was no one else in the room with you; Orton could have made a play out of such farcical restrictions. But the film makes it clear that the existence of a stupid law—which caused the downfall of another playwright, Oscar Wilde—did nothing to prevent him enjoying himself. The Guardian has another quote from him:

[The police] interfere far too much with private morals—whether people are having it off in the backs of cars or smoking marijuana, or doing the interesting little things one does.

They still do, Joe.

The web doesn’t serve Orton’s memory very well; the links below are some of the more interesting finds.

• An interview from June, 1967

• Joe Orton at the BBC Sound Archive

• Joe Orton at GLBTQ

• The Disappearing Gentlemens’ Lavatories of Old London

(A hymn to the public convenience by Dudley Sutton, dedicated to Joe Orton.)

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Passion play

• The Poet and the Pope

• Please Mr. Postman

• All you need is…

• Queer Noises