Another book design of mine (interiors only) which I completed last September for Tachyon and about which I had this to say at the time:

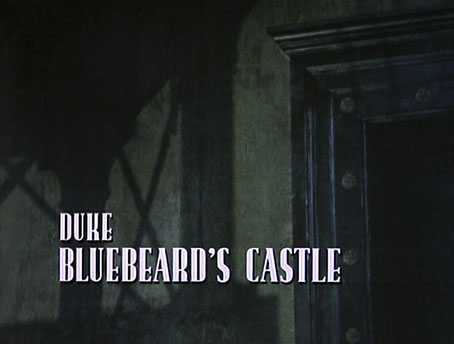

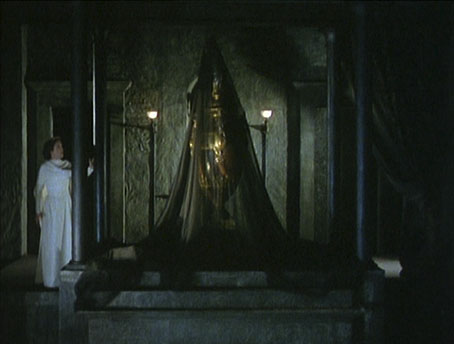

Kafkaesque [is] edited by John Kessel and James Patrick Kelly. It’s a collection of short stories either inspired by Franz Kafka, or with a Kafka-like atmosphere, and features a high calibre of contributions from writers including JG Ballard, Jorge Luis Borges, Carol Emshwiller, Jeffrey Ford, Jonathan Lethem and Philip Roth, and also the comic strip adaptation of The Hunger Artist by Robert Crumb.

The book gained a positive review at SF Site recently, reminding me that I hadn’t written anything about the design. As with some of my other Tachyon work the interiors take their cue from a pre-determined cover by another designer, in this case Josh Beatman. I followed Josh’s type choices (Senator for the titles and headings) and also extended his use of an insect as a recurrent motif. Before I saw the contents I was fairly determined to avoid any further insect imagery but it became apparent that Kafka’s Metamorphosis is a repeated reference in many of the stories.

As for the recurrent “K”, that seemed inevitable given Kafka’s own use of the letter as well as its presence not only in Kafka’s own name but in the names of the editors. The frames were an idea borrowed from (and referring to) Steven Berkoff’s stage adaptation of The Trial in which portable frames serve on the stage as doorways, windows, corridors, picture frames and so on. I was hoping to do more with this idea but (as is often the case) ran out of time to develop it further.

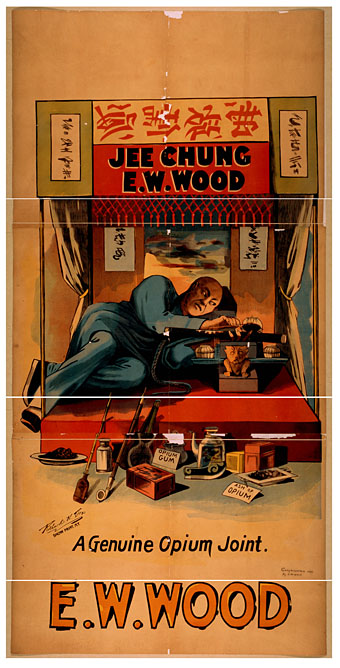

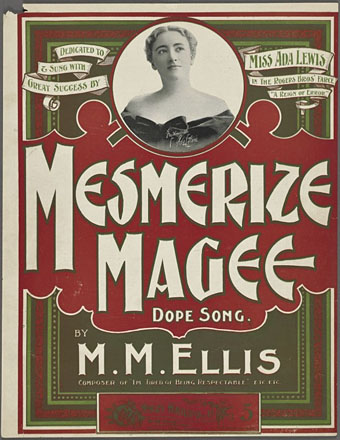

And while we’re on the subject of Tachyon designs, I don’t seem to have mentioned my interiors for a Joe R Lansdale collection, Crucified Dreams, which also appeared last year. This is a hard-boiled anthology of Lansdale’s favourite stories for which I supplied suitably rough-and-tough graphics comprising scanned scalpel blades and lettering assembled from torn newspaper pages. I’m due to start on some new work for Tachyon this week. More about that at a later date.

Continue reading “Kafkaesque”