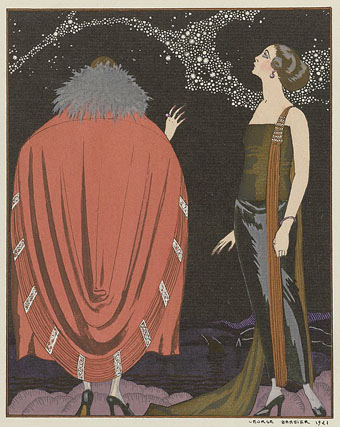

La Voie Lactée (1921) by George Barbier.

• Fun news of the week: “The Taylor Swift vinyl haunted by Britain’s weirdest musicians.” The “weirdness” is tracks from Happy Land: A Compendium of Electronic Music from the British Isles 1992–1996 which have been mispressed onto Swift’s latest, the re-recorded Speak Now. One of the offending pieces is Soul Vine (70 Billion People) by Cabaret Voltaire, a relatively understated instrumental from the Plasticity album which features samples from the Demon with a Glass Hand episode of The Outer Limits. “It’s possibly the most subversive thing we’ve ever done,” says Stephen Mallinder. Adventurous Swifties looking to broaden their horizons are advised to try The Crackdown next.

• “For McCarthy, violence is the signature of God: God, who cannot be seen, who is only indicated by an absence, who no amount of experimenting or observing will reveal, but whose existence is in evidence all around us, every day, through the apocalyptic and apophatic violence that makes up the very stuff of the world.” JC Scharl on the violent faith of Cormac McCarthy.

• Strange news of the week: Reclusive guitarist Master Wilburn Burchette (age 84) was found dead in a house with the body of his younger brother (age 76) after decades spent avoiding anyone showing an interest in his music. Numero Group, the label behind the recent reissues of Burchette’s albums, posted an interview from 2018.

• Takrar by Waref Abu Quba is “an experimental film that celebrates the timeless and intricate beauty of ancient craftsmanship. Filmed in Istanbul, the film takes us on a mesmerizing journey into the past, paying homage to Islamic, Ottoman, Greek, and Byzantine art forms.”

• “Could an industrial civilization have predated humans on Earth?” Probably not, but if it was in the deep past how would we know? Joel Froelich investigates.

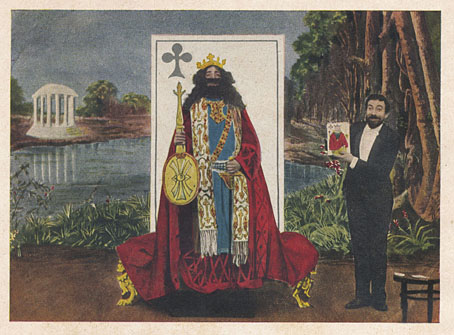

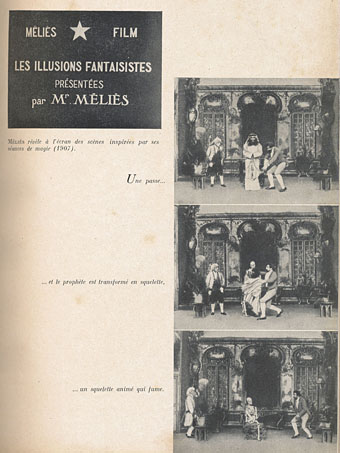

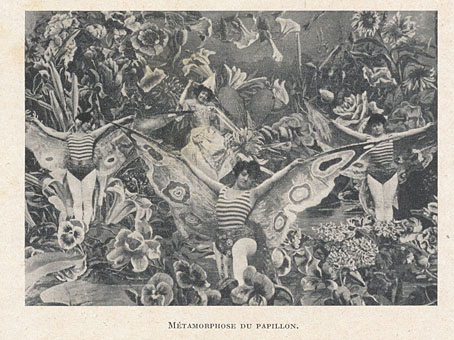

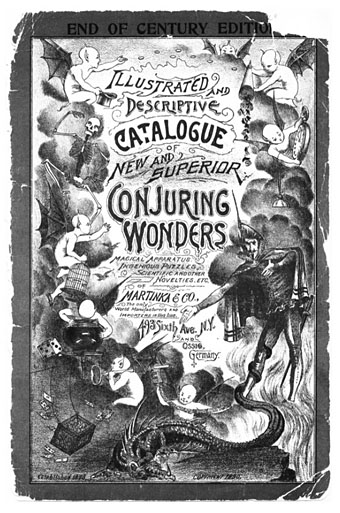

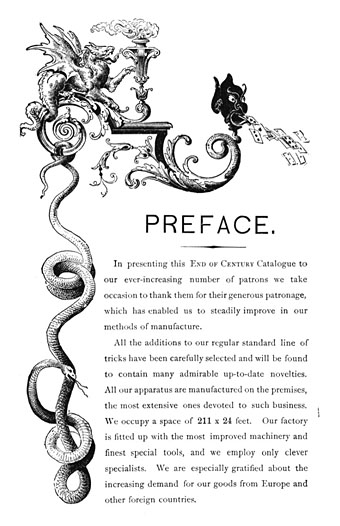

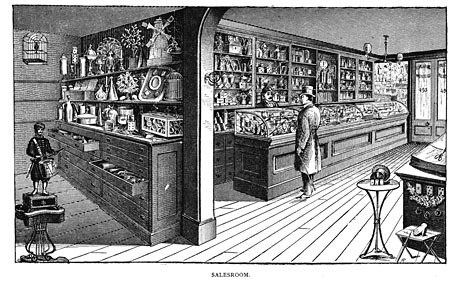

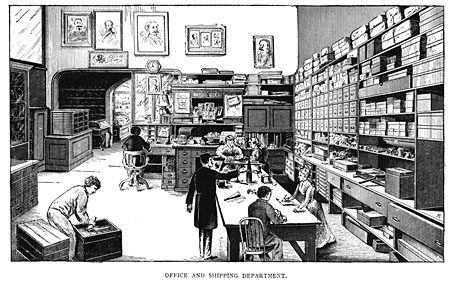

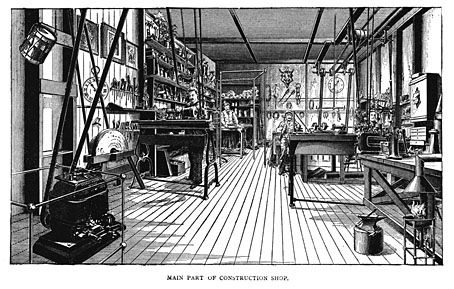

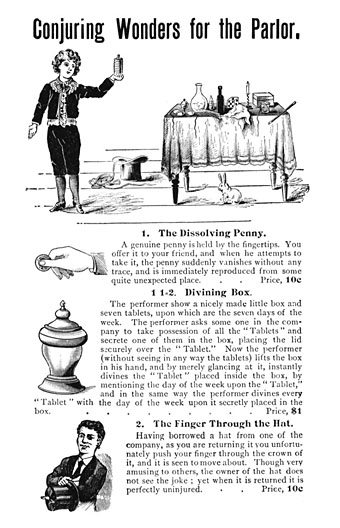

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Visual evidence from almost every museum devoted to prestidigitation in the world (for Derek McCormack).

• At Spoon & Tamago: Osaka celebrates Star Festival with river of 40,000 LED lights evoking the Milky Way.

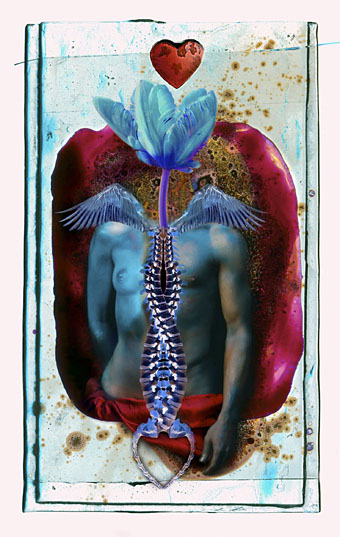

• At Unquiet Things: Even more sneak peeks from The Art of Fantasy.

• Mix of the week is DreamScenes – July 2023 at Ambientblog.

• At The Daily Heller: Sign writing and glass engraving.

• Out Of Limits (1963) by The Marketts | Trip Through The Milky Way–An Electronic Panorama (1969) by Raymond Moore | Milky Way (1971) by Weather Report